NAMM Show Report 2026

You know it, you love it, a surprising number of people have asked me when I was going to write it: it’s the NAMM report! I spent two days at NAMM this year, tried a lot of instruments, and have a lot of comments on them. For previous years, check my 2023 and 2025 articles.

Adams

Adams consistently has one of the best booths at NAMM, and this year was no different. It wasn’t much different than last year’s, but there was still a lot to be excited about.

As always, the flugelhorns were the star of the booth. For my money, Adams flugels are the best playing and sounding flugels on the market, along with the Taylor Phat Boy. It is very well known amongst trumpeters how great Adams flugelhorns are, and they might be one of the only instrument lines that everybody universally likes. Adams brought a bunch of them like they always do, and they all met all lofty expectations. It took a long time trying them all to decide which one was my favorite, and I eventually settled on a particularly gorgeous-sounding F3. As I spent awhile carefully going back and forth in between the flugels, a lot of passers-by stopped to comment how much they loved the sound. Sure some of that is me, but it’s also the instrument. I didn’t get love like that on any of the other flugels in the show!

The Adams trumpets were also very good, but not to the same level of perfection as the flugels. There were over a dozen trumpets, and unlike the flugels I didn’t love all of them. My favorite was the lone E-flat trumpet, which was a wonderful instrument. The C trumpets played well, but weren’t my cup of tea in how they felt compared to a Yamaha or Bach. The B-flat trumpets were nice, and I did really like the A1s on offer, but most of the others weren’t my vibe. The Coppernicus is always a treat to play, but I probably wouldn’t own one myself.

There were two Adams cornets, which played well but didn’t have the dark British-style sound you get from a Besson.

The trombones had a better showing than previous years. I’m still not convinced on the tenor trombones, but the TBB1 bass trombone they had this time was excellent, as was the AT1 alto trombone.

Adams euphoniums are always very good, and there was an E2 and an E3 that really stood out to me. The E3 had the edge in sound, with a really vibrant sound that the others didn’t quite match, while the E2 beat all the others in playability. There were other E2s and E3s there that weren’t quite on the same level as these two.

Adams had the same two tubas (and F and a C) they had last year, and those instruments remain standouts that are absurdly easy to play.

Sadly, Adams has yet to bring their marching brass to NAMM. I’m eager to try their mellophone especially, but I just have to hope they finally bring one next year.

BAC

I’ve played a lot of BAC instruments, and honestly I didn’t like most of them. A few of my friends here in LA have their own custom BAC horns that play really great, so I’ve always known what the company is capable of, but the demo horns at booths usually don’t meet that expectation for me. Last year’s BAC NAMM booth was a nice surprise, as they had a couple of trombones that I thought were very good. This year they upped their game again, as I thought every trombone at their booth was excellent. It’s nice to witness the progress of a company in real time. There were a couple BAC trumpets I liked a lot as well - a brushed-finish yellow brass B-flat, and a vintage finish C. The C played a lot more like a B-flat than most C trumpets do, and was a lot of fun.

Buffet Crampon

I spent very little time at this booth, as it was MUCH smaller than previous years. The Hans Hoyer Kruspe wrap double horn was excellent as they always are, and the Besson BE165 non-compensating 3+1 euphonium was quite good (but of course hampered by not being compensating). The only Courtois trombone they had was the student model, and there was pretty much nothing else except some trumpets, which I didn’t bother with this time.

Cannonball

Cannonball is a company that’s mostly focused on saxophones, but they have a small line of brass instruments as well. I thought the large bore tenor trombones (with F attachments) were pretty good, as was the small bore tenor trombone. The .525” tenor with F attachment and independent bass trombone were not that good.

Conn-Selmer

Conn-Selmer brought fewer instruments this year, which a rep told me was deliberate but other NAMM-goers I know thought it was unfortunate. Still, they had a few interesting things on offer.

Most notably to me was the Bach Peter Steiner tenor trombone. This is a model that I’ve tried multiple times in the past at previous NAMMs and at ITF last year, and every time I hated it. Very dead playing and sounding, and much worse than the Bach 42BOF that usually sat on the stand next to it. One of the Conn-Selmer reps recognized me as I walked over to their booth this year, and he told me I had to try the Peter Steiner this time, promising it was different. Well, he was right: this example of the Peter Steiner model was amazing! It had a great classic Bach sound and instant response, and was very easy and fun to play. I asked him what changed, and he said they deliberately slowed down production time on the horns, so more time is spent on each one. I told him they shouldn’t allow any Peter Steiner that doesn’t play like that one out of the factory, because that horn was what a modern Bach should be. Hopefully this is a sign of better things in the future for Conn-Selmer’s pro horns.

The Bach C trumpets at NAMM are consistently great, and the two they had here were no exception. I preferred the 229C over the 229X, and it played just as a Bach C should.

Conn also had a new compensating euphonium model, which I believe is still not for the American market. It doesn’t really matter though, because I thought it was nothing to write home about.

Other than that, I didn’t play much at the Conn-Selmer booth as it was the same stuff as last year. 8D, H179, KMP611 mellophone, a few assorted Bach B-flat trumpets, a couple other Bach large tenors, the Conn 88HNV (which I did try, and it was as okay as ever), and so on.

Eastman/Shires/Willson

Eastman-Shires always brings a lot of horns to NAMM, and such was the story again this year. They had some notable new models, as well as other models that have been present at the booths in previous years. I focused mostly on the new models.

The biggest draw, of course, was the new Shires Q38 and Q39 contrabass trombones. They brought both versions, the Q38 in European tuning and the Q39 in American tuning. I played the pre-production Q38 at ITF, so I knew what to expect, and the Q38 at NAMM was very solid. Weirdly though, the Q39 was a lot worse. It was much stuffier and not easy to play, which does not bode well for the average quality of these instruments. While they are cheaper than the high-end European instruments that cost as much as a decent used car, $7k is still a very large sum of money to spend on an instrument that might be good. It’s not a good sign, especially when Shires is usually excellent at bringing the best possible examples of their horns to conventions.

The other interesting new model at Shires was the Vintage LA bass trombone. This is a single valve bass that they say was designed in the Williams style. From the start I don’t really know why they decided to make this instrument, as nobody is asking for a new Williams-style bass trombone, let alone one with only one valve. If any region would be interested in it, it’s here in southern California, but even here we don’t really get the point. And unfortunately, it only gets worse from there. First, it did not play or sound anything like a Williams. Second, ignoring the Williams influence it just didn’t play well to begin with. And third, it is so front-heavy that it’s really not usable at all. No counterweight, no braces, and only one valve is an obvious recipe for left hand injuries. This thing is useless, and I have no idea how or why it was approved for production.

Shires also brought the slightly less new Vintage LA small tenor trombone, which was also apparently intended to be like a Williams. But just like the bass, it just isn’t. I have played multiple Williams 6s from different eras of production, and they are still the best small bore trombones I’ve ever played. The Vintage LA tenor is nothing like that in sound or feel, and I also just don’t think it’s very good on its own either. I tried this model at ITF last year, and had the same opinion. I’ve spoken to a few other top studio LA trombonists who were there, and they have the same opinions as I do about both Vintage LA instruments. They are just not good, and not even in the same dimension as the instruments they’re supposed to be emulating.

In better news, the Shires Rejano large tenor is still amazing, and the Shires Q41 is still one of the best euphoniums on the market. The Willson Q90 euphonium is still a mystery to me, as it seems like it’s not much different than the Q41, except for having the signature Willson bracing. They play very similarly, but I prefer the Q41 overall. A new model this year was the Willson K56 euphonium, which slots below the Q90/Q41 in the lineup. The K series sits in between the student A series (which are still often excellent, pro-quality instruments) and the Q series. I found the K56 to be a very good instrument, not quite as good as the Q90/Q41 but also retailing for $1k less. For those whose euphonium budget tops out at $6k, I think the K56 is a great option. I prefer it immensely to every Eastman euphonium I’ve played, as well as the Besson BE165. There is also a K46, which is a non-compensating 3+1 version and the real competitor to the BE165. I think the Willson A27 (which might be my favorite euphonium they make) and K56 are the only cheaper-than-Q41 euphoniums worth considering in the Shires/Willson lineup.

Eastman brought a bunch of tubas, and I tried the 834 (4/4 C) and 836 (6/4 C). Both were excellent, which is not surprising as so many people play Eastman tubas. I have yet to play one that isn’t top tier.

Shires also brought their new Custom series double horns, as long as the Q-series double horns from last year. All were yellow brass Geyer wraps, and I didn’t really like any of them. I had better luck with the two Shires flugelhorns, which were not great last year but much better this year. Both were very good, but I preferred the Q19.

I didn’t spend much time with the Shires trumpets and cornets this year as I tried them all last year, but I briefly tried a couple at random and found them very good as before. The 4S8 C trumpet was the standout for me.

Apart from the tubas, the only Eastman-branded instrument I tried was their marching mellophone, a clone of the Yamaha. I wasn’t a fan.

John Packer/Rath/Taylor/Sterling

The JP family booth was once again huge, with lots to try. A lot was the same as last year, but I still spent quite a lot of time at the booth trying everything. The reps also immediately recognized me from last year, which felt good!

Rath had a fleet of trombones there, and my favorite was the yellow brass R2. Since my main small bore tenor is a King 3B, the R2’s .510” bore feels right at home, and I had lots of fun playing it. The Rath reps could apparently tell, because they ended up filming me playing it and posting it all over their social media, which was fun.

There was a nickel-bell R3F as always, which I appreciated because I can’t get enough of that instrument. I think there is some magic in Rath’s nickel bells, and they pair so well with the R3. I’d love to own a nickel bell R3F one day. As before, I found the R6 to be excellent and much better than the R4F next to it. The R9 and R9DST were good, but not my favorite examples despite being pretty standard configurations. The R11 alto was very nice.

The cheaper side of the trombones held some surprises. The John Packer 131, which is the lowest model in the range (and apparently identical to the BAC Elliot Mason student model), was excellent. I’d even say it was one of the best trombones at the booth. The JP Rath 231 next to it was also very good, as were the Rath R100 and JP Rath 333 bass trombone. I’d gladly own and play any of those instruments.

John Packer also recently acquired Sterling when the original single craftsman retired, and they brought along their new euphonium and baritone horn models. The euphonium was very good, but the baritone horn was exceptional. They said they have a tenor horn in the works, which I’m very excited about if it plays anything like the baritone does.

There were a ton of Taylor trumpets as usual, and there were some new favorites. The star for me was the short model Taylor E-flat trumpet, which was my favorite instrument in the entire show this year. It played SO easily, as all Taylors do, but it was another level on this particular horn. And despite being an E-flat, it sounded much bigger, like a big C or even B-flat. I was addicted. There was another heavier E-flat with a red bell and sheet metal bracing that I didn’t like as much, but that yellow brass E-flat is a new dream horn for me. The Orpheus cornets played great but didn’t have that dark British sound I look for in a cornet, and the B-flat trumpets all played very well but none stood out to me, except for visually. There was an incredibly heavy trumpet with a hexagonal bell that was wild to look at and even wilder to hold, but still played great, and of course there was the trumpet with sharp bends they’re famous for, which also played great. Sadly Taylor didn’t bring along the Phat Boy flugelhorn this year, instead only bringing their odd trumpet-shaped flugelhorn, which I didn’t like at all.

Finally, Taylor also had a trumpet with bent leadpipe so the bell pointed upward - essentially the sax-shaped trumpet thing (properly called a soprano normaphone) but done in a jankier way. I did not enjoy playing it, as it did not seem very well thought out even compared to the two Chinese normaphones present at NAMM.

Schilke/Greenhoe

The Greenhoe trombones at NAMM this year were ALL some of the best in the show, just as they were at ITF last year. The Conn-style GC4 tenor/GC5 bass, the Bach-style GB4 tenor/GB5 bass, and the GC2-Y/GC2-N jazz horns, were all wonderful instruments that I would gladly play every day. My favorites were the tuning-in-bell GC4 tenor and the tuning-in-slide GC5 bass, but for my money all of the basses were better than any other bass at the show. Greenhoe really has it down right now, and it’s great to see.

I didn’t spend too much time in the Schilke side of the booth, as it was all the same horns as last year, which I tried extensively then. I did try the two flugelhorns they had, one of which had a screw bell. Good horns, but can’t compare to the Adams flugels. I really like Schilke trumpets, and the brief time I spent on a few of them just told me what I already know. They are great!

Valkyrie (Opus)

Valkyrie/Opus was back with a big booth this year, and it was hard to get some time there as there were often banda players flocked around it giving impromptu banda concerts (which was awesome). A lot was the same as last year, including the brushed-finish nickel marching euphonium and their normaphone (sax-shaped trumpet). There were two new interesting things, though.

First was a purpose-built mellophone mouthpiece, not sold separately but sitting in their King 1120 clone. It had a much bigger rim than most modern mellophone mouthpieces, closer to the Conn 1 that the Conn 16E mellophonium came with. I found the rim very comfortable, but unfortunately the mouthpiece was wayyyyy too deep and the high register (or any edge to the sound at all) was completely nonexistent. Still, I was excited that a Chinese company bothered to make a new mellophone mouthpiece instead of just including a trumpet mouthpiece.

The other new thing was a very small sousaphone. This is an instrument still in contra B-flat just like a normal sousaphone, but MUCH smaller in every dimension. It’s also much lighter as a result, which meant I was happy to try it on and see what was up. It was a good player, with a much raunchier sound at low dynamics than most sousaphones. Not so much when I played it, but when the banda guys got a hold of it, they made it scream. It seems perfect for that kind of sousaphone playing, but I also had the thought that it would work as a sort of cimbasso with the right mouthpiece. It would be interesting to experiment more with it, but I was glad I got to try it and very happy a company would try something different.

The rest of the horns were business as usual for Valkyrie. The normaphone, marching euphonium, marching baritone (Yamaha copy), and tenor horns were all good. The C valve trombone, in silver this time, was not as good of an example as in NAMMs past, but still decent. The King mellophone clone was fine, nothing special.

Yamaha

The brass portion of Yamaha’s huge 3rd-story booth essentially ran it back from last year, so there’s not much to say about most of what’s there. The BR trumpets are still the best in show, with the non-BRs only slightly behind, the YBL-835D bass trombone is still very good, the tenor trombones are still so unfun to play, and the euphoniums and tubas are still some of the best in the business. My favorite instrument at NAMM last year, the YHR-872ND Kruspe-wrap double horn, is still as pure magic as I remember. This year it brought a new stablemate, the YHR-871II Geyer-wrap double horn. This horn was just as easy and addicting to play as the 872, and one of the best factory horns out there, but ultimately I still think the 872 is the magic horn with the magic sound. For some reason, Yamaha also threw a plastic valveless Bb bugle in with the trumpets. It sure played notes!

ZO

ZO is always one of the booths I look forward to the most at NAMM, because they have so many great and unique instruments. I started with the travel line of tubas, euphonium, and baritone, only spending a brief time on each because I’ve already played them many times. They are just as great as ever, sounding MUCH bigger than they are. The brass tubas also met expectations from previous years, and were excellent across the board. One difference from years past is the plastic tubas with brass valves. In previous years they did not play very well, but they must have updated the model because this year I thought they were very good. I would love to have one for polka gigs and really anywhere that a light tuba is advantageous.

The compensating euphoniums were solid but nothing special, similar to some other Chinese euphoniums. I’d say the same for the brass French horns (single and double) that I tried - there was no standout like before. ZO brought along two new plastic single horns instead of the plastic double horn they had last year. One of the singles was in B-flat and the other in F. The F was not great, and was very out of tune with itself. But the B-flat was great! It played great, responded lightning quick, and had a nice bright sound that would be perfect for outdoor and jazz applications. I was a big fan of this one! And of course, extremely light, so nice for long gigs.

Continuing with the plastic instruments, they had multiple examples of their trumpet, cornet, and flugelhorn. I didn’t bother with the trumpet as I didn’t like it last time. The cornet was just okay, but the flugelhorn remains quite good and something I could absolutely envision picking up as a car and travel instrument for the right price. The plastic euphonium and F-attachment trombone were the same story as before (not great), and the plastic small bore tenor with the King-style curved brace was also the same as before (amazing). I actually wanted to buy one of the plastic small tenors, but when they told me they only accepted cash I lost interest. Who’s going to walk around NAMM with hundreds of dollars in cash??

Anyway, the brass trombones were a mixed bag, with the small bore being the standout. Just like last year, it was very good and fun to play.

I did end up buying two trumpet mutes from ZO. They were there last year, I liked them, and kinda regretted not buying them afterwards. So when I saw they were here again this year, and only $10 each, I gave them $20 cash and walked out with them. They are good, fun little plastic mutes!

Other Manufacturers

As always, NAMM featured a variety of Chinese manufacturers trying to break into the American market. There were some interesting instruments this year!

Hunter had a small booth like they always do, and while I found their compensating euphonium and double horns meh at best, their King mellophone clone was the best one there. It was very good!

Jiangyin Seasound only had a few brass instruments, but one of them was a normaphone! It was the best out of the 3 there (Seasound, Valkyrie, Taylor) by a big margin, and the only one that really felt like an instrument I’d really play instead of just a gimmick. It was excellent! Their normal trumpets were very good as well, and they even had a clone of the Taylor trumpet with the sharp bends. I was impressed with everything they had on offer.

New Bee Music Supply was an interesting one, only carrying standard B-flat trumpets but in a few crazy finishes. My favorite was the pearlescent color-changing finish. They were all pretty good instruments, nothing to write home about it but fun party horns.

Conclusion

That was my experience at NAMM this year! I didn’t try everything, especially a lot of the things that were there in years prior, but I still spent a full two days going around trying a lot of stuff, running into a bunch of friends and colleagues, and generally having a great time. It was also exhausting though! That much walking will take it out of you, but it’s always worth it.

The G Valve

For trombones with a single valve, a valve loop tuned to a perfect 4th below the open horn is the universal standard. This is the F attachment on a tenor or bass trombone, or Bb attachment on an alto. Trombonists generally just accept that that’s how their valve is tuned without giving it a second thought. After all, we must have settled on a perfect 4th for a reason, right?

After all, in the early days of brass instrument valves, other tunings were tried. Turn of the century trombones sometimes had their valve tuned to a tritone (E attachment) instead of a perfect 4th (F attachment), for example. And, logically, the F valve on a tenor-bass trombone makes logical sense in theory; you combine the tenor trombone in B-flat and the old bass trombone in F into one instrument. Right???

Well, not entirely. The bass trombone in F has a full length slide that allows you to play low C and B. The F attachment doesn’t really have access to either of those notes. Yes, I know generations of trombonists have accepted the common wisdom that low B is the only note missing on an F attachment, but unless you have an extra-long handslide like on a Conn 70-series bass trombone or some traditional German trombones, that’s not actually true. Modern trombone slides are too short to actually be able to play an in-tune low C at the end of the slide. Of course, players learn to adapt, and many a powerful low C has been played on a modern single-valve trombone. But in these cases, the low C is being lipped down into tune (and sometimes the player doesn’t even realize that they’re doing this, because low C is supposed to be at the end of the slide!) …or it’s just very sharp. In any case, this point is only somewhat important to the real topic at hand, so I digress.

Anyway, the F attachment obviously works well enough that there isn’t a strong reason for most trombonists to consider trying a valve tuned differently. The hardest repertoire ever written for the trombone has been played brilliantly on trombones with F attachments.

However, a perfect 4th valve is far from the only way to get the job done. And, more to the point, there is another way to tune the valve on a single-valve trombone that I would argue is significantly better than the F attachment for the majority of players. Enter the minor-third valve, aka the G valve on a tenor or bass trombone.

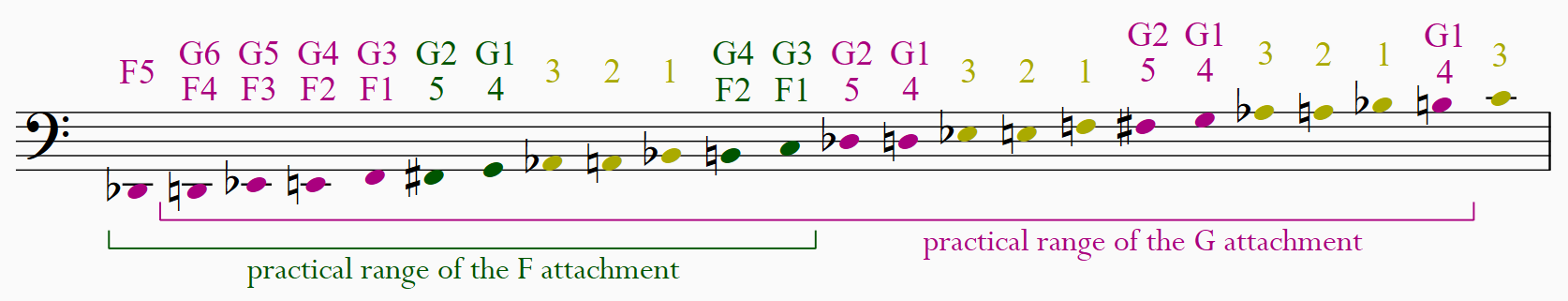

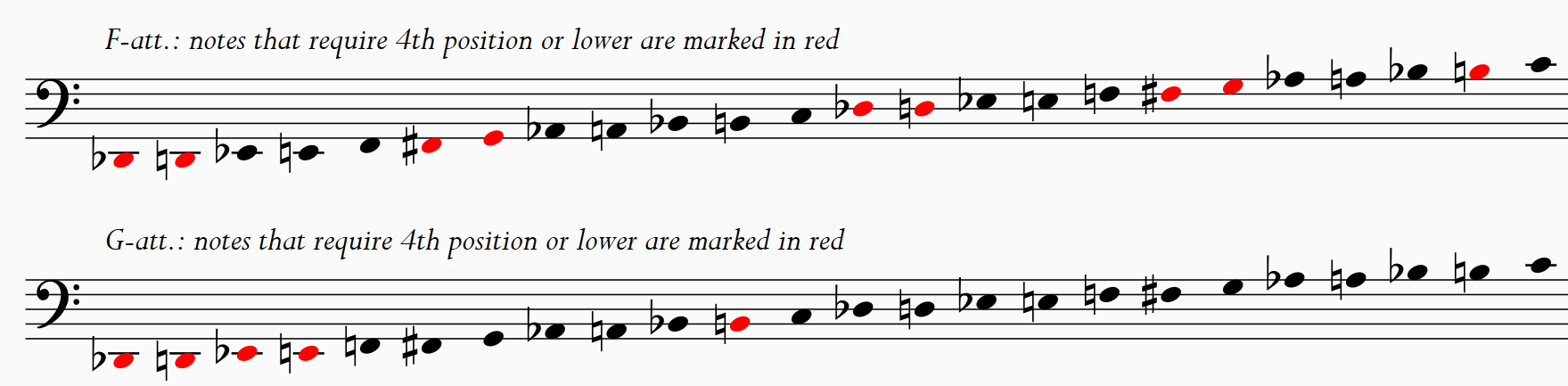

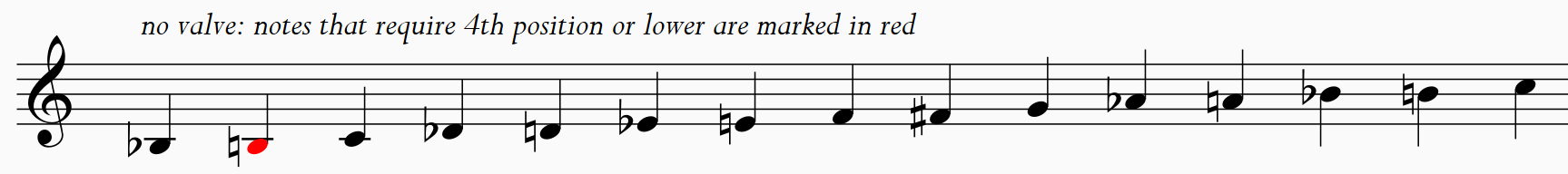

The minor-third valve (G attachment) does as you would imagine: rather than lower the pitch of the trombone by a perfect 4th to F, it lowers it a minor 3rd to G. Put another way, you are using a 3rd valve on a typical valved brass instrument instead of a 4th valve. With the G attachment, you have a range down to low D right in 7th position, so you are really only losing one real note (Db) to the F attachment. Below the staff the F attachment is more convenient, but the notes are still perfectly doable on a G valve. However, once you get into the staff, the G valve becomes drastically more useful than the F valve.

Shown above are the practical positions for the F and G attachments. This is obviously not every possible note the valves can play, but instead the notes that are either not possible without the valve, or they replace the only or most common open slide position. This is an important distinction because, for example, you can play A3 (top of the bass clef staff) in T1 with an F valve, but doing that is the equivalent of playing it in 6th position on the open horn, which is something that is rarely needed when you have a much better option in open 2nd. Contrast that with the B at the top of the staff you have access to in T1 with the G valve. Playing this note in T1 is functionally identical to playing it in 4th position without the valve, which is the standard position for that note. Yes, you can also play it in 7th (which is what playing it in T2 with an F valve is equivalent to), but you would never do that except for specific circumstances like glissandi because 4th is much more secure.

With this criteria in mind, you can immediately see why the G valve is much more useful than the F valve in the staff. The F valve’s highest practical note is C in the staff, while the G valve’s highest practical note is B on top of the staff, nearly an entire octave higher. And on tenor trombone especially, notes in the staff are infinitely more common than those below it, so why would you greatly reduce your valve’s utility in a range you play in constantly to only get a minor improvement in a range you play in occasionally?

With that usefulness in the staff comes the G valve’s greatest strength: with a G valve, the agility you can achieve in the staff is equivalent to that above the staff, an octave higher. There is a reason jazz trombonists often hang above the staff when playing solos at fast tempos; once you get above the staff, you never have to go past 3rd position, so you are far less encumbered by the physical distance you need to move the slide. With a G valve you never need to go past 3rd position all the way down to C in the staff, which is a full octave lower than without a valve and a perfect 5th lower than with an F valve.

I own several trombones with minor third valves: an alto, a small tenor in C, a medium bore tenor, a large bore tenor, and a bass trombone (valves in G and E). They have each proven to me just how useful the minor-third valve is many times over. Of course I own tenors and basses with F attachments as well, and they do the job just fine. But when playing on one of my single F attachment trombones, I often find myself wishing the valve was in G. It is just infinitely more useful for most playing situations.

Of course, there are times when you do need an F attachment. The unison, exposed low D-flat in Mahler 3, for example. But providing an F extension, or even a Gb extension, for a G attachment is perfectly doable and covers these eventualities. When playing a single-valve bass trombone, you deal with a lot more writing below the staff, so in that case the F attachment makes more sense, especially if it has a flat-E pull for a true low B. But for alto trombone, tenor trombone, and even plenty of bass trombone repertoire, the G valve would not only do the job, but do it better than an F valve.

A Shires tenor trombone with a G-flat attachment. The G-flat/major 3rd valve could be a nice compromise for orchestral tenor players who do need the occasional low D-flat, or bass trombonists used to the G-flat valve on an independent bass trombone.

At the end of the day, 99.99% of trombone players will never get a chance to try a G valve for themselves because nobody sells them. Of course custom makers can always do custom orders, but most players would (understandably) want to try a new tuning before committing to an expensive custom order. Not many people will be willing to chop up an F attachment to give the G valve a shot, which is also fair. The only real way for the G valve to gain more widespread appeal is for manufacturers to offer it off the rack, WITH an F extension as standard equipment. Then, just maybe, more people will realize just how great the G valve is, and just how suboptimal the F valve is for a lot of trombone playing.

Thank you for coming to my TED Talk.

ITF Exhibit Report 2025

This month (July 2025) I traveled to London, Ontario to be a featured artist at the 2025 International Trombone Festival. It was an unforgettable experience that I could write a novel about, but I was specifically asked (by multiple people!) to do a write-up of all the trombones I tried at the exhibit hall, so here we are.

Before we begin, I have a couple of disclaimers: 1) the exhibits were smaller than usual, I suspect due to the ongoing trade nonsense, and 2) a lot of the instruments there were models I already tried a few months ago at NAMM, so I did not play everything. I revisited some of them, but for the most part I skipped over the instruments I’d already tried this year. For my opinions on those, see my NAMM 2025 report.

Conn-Selmer

I have nothing too special to report from the Conn-Selmer booth. They had a couple of prototype improved CL 88Hs (one yellow bell, one red bell), which I thought were both worse than the 88HNV next to them. The 88HNV was the best Conn tenor…and it was just pretty good. The Bach side of the booth was a similar story. I thought the 42BOF played the best of anything at the booth, but that was also just good, not great.

Courtois

Courtois showed up with an octet of trombones, which were quite popular on the second day. I tried all but two of them, the 551 bass and the Mezzo 280 large bore tenor.

One of the highlights for me was the trio of Creation tenor models all next to each other. I had tried (and loved) the New Yorker at NAMM 2023, and tried (and loved) the Florida and Paris models at NAMM 2025, but never back to back. I played them all back to back to see how they stacked up against each other. The New Yorker was the yellow bell model, rather than the gold bell model at NAMM 2023, but otherwise it was all the same. I went in expecting to like the New Yorker the best, but I actually ended up picking the Florida as my favorite, followed by the Paris. All three horns were excellent and fun to play, but the Florida was so easy to play and the Paris had a special sound and blow. I’d be happy to own any of them, but if it was my choice I’d walk out with the Florida model.

The 402 Xtreme (.508”) was just as I remembered it from NAMM 2023 - plays exactly like a King 3B (which was by design), but with a more refined sound. A very nice instrument that I’d be very happy to own and use every day if I didn’t have my 3Bs. The 430 Xtreme (.500”) played very similarly to the 402, but it felt too tight to me. It’s not a big-feeling .500” like a 6H, 2B Plus, or Williams 6…it feels closer to a 2B to me. Definitely a nice instrument for those that prefer smaller horns.

The last Courtois I tried was the Mezzo 260 intermediate model, pretty much just because it was a .525”. It played well enough, nothing to write home about but nothing spectacular either. Definitely a true intermediate horn, rather than a world-beater mislabeled as “intermediate”.

Courtois also had the new Besson 969 euphonium (from their parent company Buffet Crampon) there, but I didn’t play it because I had tried it extensively at NAMM 2025. It was my favorite euphonium at NAMM!

Eastman-Shires

The big news from Shires was of course the new Q-series contrabass trombone. I tried it and thought was pretty good - definitely a significant step up from the Chinese contras (including Wessex). I could play up to A above the staff down to the lowest notes with a consistent sound - not too dull or woofy, just a nice very big trombone sound. It’s far from the best contrabass trombone I’ve played, but for a price that I assume will be significantly cheaper than the handmade German instruments, I think it’ll be an excellent option that won’t feel like it’s holding you back.

I only tried some of the other Shires instruments at the booth, as I played a lot of them at NAMM and I also just kind of know what to expect from Shires at this point. Highlights were the Rejano model (I checked to see if it was still as great as it was at both NAMMs I tried it at, and I’m happy to report that it is) and a random custom tenor with a gold bell and a Trubore (seen roughly in the top middle of the photo above) which was excellent. The rest that I tried, including the new “Vintage LA” jazz horn, were what I usually expect from Shires: easy to play, but uninspiring.

Greenhoe

I was pleasantly surprised with Greenhoe’s offering at ITF. While I played some good Greenhoes at NAMM, nothing was too memorable compared to other things at the show. However, I think Greenhoe had the 3rd best instruments at ITF, after Thein and Littin. I didn’t gel with every instrument they had, but I liked several very much - and this is after trying the Littins and Theins! The two GC2 jazz horns there (one yellow bell, one nickel bell) were both excellent - for my money, the best jazz horns at the show. The tuning in slide Conn-style large tenor and bass were spectacular instruments, with that vintage Conn-like sound I love so much. It felt like coming home. I also really enjoyed the yellow screw bell, lightweight slide large tenor (seen on the far right above) - super snappy response, great lively sound, and just a fun horn to play all around. I’m not sure if that was a GB5 or a GC5, but based on how much I liked it I would guess it was a GC5. I should have checked!

Littin

I had heard nothing but rave reviews about Littin, a new German maker, so I was delighted to discover they had a booth at ITF. I tried all 6 instruments they had on offer, and while I felt the bass was straight up bad and the alto was just ok, the tenors were very special. Of the four, my favorites were the Szabo model without the valve weight (2nd tenor from the right above), and the Abbie Conant model with the valve weight (to the right of the Szabo). I couldn’t decide which one I liked better, but with a gun to my head I think I’d pick the Conant model. They were both absolutely exquisite instruments…true works of art shaped like a trombone. The response was instant, the agility effortless, and the sound captivating. I could not put them down, and I could have easily stayed there playing them all day long. They were intoxicating instruments, and as other instruments have done for me in years past, re-taught me just how wonderful a large tenor trombone can be. New dream horn unlocked.

Also shout out to the Littin rep in the picture above, who was so kind and definitely the most fun rep to interact with in the whole show.

Thein

Speaking of dream horns, the Theins were so popular that every time I walked by there were fewer horns on display as people bought them! I tried eight of their instruments, starting with a Universal alto and Maxim jazz trombone. Both were very good - nothing that I would spend Thein money on, but very good nonetheless. The Universal and Hecht bass trombones were excellent with my Bach 1¼GM, while the Ben van Dijk bass trombone really came alive with a Thein BMW mouthpiece that Max Thein had me try after it was clear that the horn was not a good fit for my mouthpiece. All three basses were fantastic instruments that I would happily own and play, but again…for Thein money? I’ll keep my 72H!

There were three large tenors - a Universal I, Universal II, and a more American model with axial whose name I don’t remember. That axial instrument didn’t gel with me very much, but the two Universals sure did. Much like the two Littin tenors I had fallen in love with minutes prior, these two Universal tenors totally captivated me from the first note. They sounded very different from each other, but each sound was very special and addicting. The Universal I was my favorite between the two, with a gorgeous, colorful, European sound that I couldn’t get enough of. And like the Littins, the response was instant. These two Theins and the two Littins all fall into a category I like to call telepathic instruments - instruments that feel like they are reading your mind as you play them. It was very hard to stop playing the Universal I, and Max Thein told me that I sounded very connected to that instrument, playing from the heart in a way he didn’t hear from any of the other Theins at his booth.

I truthfully have no idea if I would walk out with the Thein Universal I or the Littin Abbie Conant model if I had the kind of money to do that…I would have to play them back to back, probably for hours and with trusted ears listening. But I do know that either one would be a forever horn, and I have a new target to aspire to one day.

Yamaha

Yamaha always gives a good showing at conventions, and ITF was no different. I spent quite a bit of time at the Yamaha booth, chatting with the reps and being a nuisance on the valve trombone. Most was what I expected, but there were a few surprises along the way. I’ve also tried Yamaha’s entire lineup at one point or another, so there was a lot I skipped over this time.

The biggest surprise to me was how the YSL-882II and 882GII large tenors felt. If you’ve read my NAMM articles, you’ll know that I place the 882 (not 882O or OR) on a pedestal and think there is something magic about it that no other current Yamaha model has. To me the 882II was easily the best large tenor at NAMM 2025, beating out a few truly excellent instruments like the Shires Rejano and Rath R6 without much effort. But ITF was different. I walked straight from the Littin booth to the Yamaha booth, and straight to the 882II at that. And compared to the Littin tenors, the 882II felt…sluggish. Dead. Disappointing. It became clear to me that I hadn’t tried any of the exquisitely-handmade German tenors since ITF 2016 in NYC, nearly a decade ago, and I didn’t know what I had been missing.

Despite this, I still maintain that the 882II is one of the best large tenors you can buy if you don’t have Thein or Littin money. I tried the yellow-bell 882II and gold-bell 882GII back to back, and found that I preferred the 882GII for its slightly more interesting sound.

I didn’t bother with any of the other large tenors or basses, as I’ve tried all of them (including the new 835 and 835D basses) many times at NAMM and elsewhere. I did finally try the YSL-350C tenor, which has an ascending C valve. I’ve been researching and writing about ascending valves for a long time, and I knew I would probably love it in practice. And I was right! It was very fun to experience playing an ascending C valve on a trombone for the first time. Unfortunately, the instrument the ascending C valve was attached to had a very boring sound…but it was still a fun experience.

The Yamaha altos were fine, nothing special but nothing bad either. The YSL-354V valve trombone was great fun to noodle on. I never saw anyone else even touch it when I was there, but I had a hard time putting it down each time I walked by and picked it up. Definitely not the best valve trombone out there, but it sure is fun!

Y-Fort/Princeton/Sierman

I’ve lumped Y-Fort, Princeton, and Sierman together because they were all in the same booth, all brought by the Y-Fort guy even though he only represents Y-Fort.

I didn’t try the Y-Forts because I own one and I tried them all at NAMM, so nothing would have been new there. I felt the Siermans played as heavy as they felt, and wasn’t really a fan. The Princetons were a mixed bag, but there was one large tenor they had with a red bell that played great! Very nimble and quick-responding, with a nice sound. I was told that model retails for $1700, so around Y-Fort price. I’m not sure I would choose one over a Y-Fort, but they don’t feel or sound the same so there are now multiple good options at that price point, which is exciting!

Flugabone

While the flugabone is certainly an uncommon brass instrument, it isn’t nearly as obscure as many of the others on this website. However, it is still niche enough that many brass players are unsure exactly what it is, or how you can use one. In addition, there have been many different models by many different manufacturers over the years, and I thought it would be useful to collate them all.

First off, what is a flugabone? It may be simpler than you expect: it is literally just a valve trombone wrapped like a trumpet, just as the trombonium is just a valve trombone wrapped like a bell-front baritone. Flugabone, trombonium, and valve trombone all play essentially the same, so why do they all have different names? The answer is simple: marketing. American manufacturers have had a habit of inventing new names for less-common instruments for marketing purposes, especially in the first half of the 20th century. (See also: “Holtonophone” for Holton’s sousaphone.) King was one of the most common offenders, and King coined both “flugabone” and “trombonium”, for their models 1130 and 1140, respectively. While other manufacturers often use other, more generic names, the name “flugabone” has become the generic term for this type of instrument, as the King 1130 is the most well-known, and it’s much snappier to say “flugabone” than “marching trombone” or “compact valve trombone”.

In my opinion, the flugabone is the superior choice compared to a trombonium or traditional valve trombone, entirely because of the form factor. It is more ergonomic, more compact, and much more convenient to carry around than the other two. Valve trombones and tromboniums generally have horrendous ergonomics, while flugabone is perfectly comfortable to hold. The flugabone can also be played one-handed, which is a nice additional perk. I have owned all three types, and the flugabone is the one that I’ve kept around.

So, what kind of flugabones are out there, and how are they different?

We’ll start with the eponymous King 1130. This instrument is an excellent player, with a loud, shouty sound that is perfect for playing in street brass bands or with amplified groups. Although I have owned flugabones that played a little better than the King, the contexts I use my flugabone in the most benefit greatly from the King’s punch and projection, so that’s the one I’ve stuck with. The King is fairly mouthpiece sensitive; if you use a mouthpiece too small or shallow, it will get very barky, and not in a good way. And if you use a mouthpiece too deep, it just sounds like a malnourished baritone horn. But if you use the right middle-of-the-road mouthpiece, it is incredibly fun and plays incredibly well. I use a Hammond 11M in mine, and it is an excellent match. The 1130 has a .500” bore and 8” bell.

Like all of King’s marching line at one time, the King 1130 was also stenciled as a Conn, in this case the 138E. Kanstul’s flugabone, the 955, was a clone of the King. I’ve played a 955 and it played quite a bit heavier and less lively than the 1130, but it could have been just that example. Dynasty and Weril have made several King-like flugabone models, including the M565, M566, M567, Weril F371, and the Cellophone in G. Most modern Chinese flugabones (Lake City, Wessex, Schiller, etc.) seem to be based on a specific King-based Weril design that departs from the King wrap significantly on the left side of the instrument. I haven’t been able to determine the model number of that specific instrument, but I would guess it preceded the M565/F371.

In addition to the cellophone in G, the basic King design also led to what I assume is the only factory-built flugabone in C, the Weril F310.

After the King, the next most common kind of flugabone is the Olds O-21. Olds marketed the O-21 as a “compact valve trombone”, and the basic design was then used and by several other makers, including Bach (883), Reynolds (TV-29), Blessing (M-200), and Boosey & Hawkes (Regent). The O-21 is more compactly wrapped than the King 1130, but it loses the 3rd valve slide kicker as a result. It has a larger .515” bore, and is freer-blowing than the King as a result. It is more refined, as well; the O-21s I’ve owned and played sounded closest to a slide trombone out of any valve trombone of any type that I’ve played. If classical flugabone gigs existed, the O-21 would be the flugabone to use. But it is excellent at everything you might want a flugabone for. I have owned 2 O-21s and trialed another in like-new condition, and it was hard to let any of them go. But what I really don’t need is multiple flugabones, so I stick with my King. I also owned a Blessing M-200, which played similar to the Olds but leaned more towards smoky jazz playing. I used it for exactly that on a run of very quiet, background music jazz trio gigs, and it was better at any other instrument I owned for that role. It sounded so good played softly, and it could get VERY soft.

Generally, the two families of flugabone designs detailed above are the only flugabones people know of, and the only ones that turn up for sale. But there are actually two other types of flugabones that are much rarer, at least outside of Brazil.

The first centers around an older Weril flugabone design, whose model number (if there is one at all) I am unaware of, but have seen listed as models “Junior” or “Bentley”, each stamped on the bell of that instrument. This model has also been cloned by Chinese makers. Although it is essentially unknown in the English-speaking world, this model of trombonito (as flugabones are called in Brazil) is common in Brazilian classifieds.

The final type of flugabone that I’ve come across, very rarely, is the DEG compact marching trombone. This instrument was built in the 1970s for DEG by Willson, like all of their DEG’s marching brass at the time. I have only ever seen a handful of online sale listings for this instrument over the years, and as you can see from these pictures from two of them, the design clearly evolved over the years. Like all of DEG’s Willson-made instruments, I have read high praise about how this flugabone plays, but I have yet to have the chance to find out for myself. I have a suspicion that, just like more common DEG/Willson 1220 alto cornet made during the same period, this instrument is really a tenor cornet, with conical leadpipe and cornet-like bell taper.

In recent years, the demand for flugabones has actually been quite high from trombonists, similar to the bass trumpet. As a result, used prices can be quite high. However, you can still find flugabones for cheap if they are mislabeled as a mellophone or marching baritone in the sale listing. I have owned four flugabones, and I bought all of them on eBay for very cheap prices.

So why do people want flugabones so much? I think it’s the convenient/ergonomic form factor compared with just being something different, for both trombonists and trumpeters. The players I see with them are generally jazz, funk, and/or commercial players who want a new sound in their arsenal. For trumpeters, it’s the most logical low brass double in many ways, as the design and ergonomics are very similar to trumpet. And for trombonists or euphoniumists, a good flugabone is much more easily available and affordable than a good valve trombone, and a flugabone has many advantages anyway. The flugabone might be the perfect instrument for brass players who want a new sound to play with that they can actually use, but also don’t want to spend a fortune or play something uncomfortable. I know trumpeters, trombonists, euphoniumists, tubists, and even hornists who have picked up flugabones for all of the above reasons. The DEG alto cornet previously mentioned has the same charm for those who are comfortable playing in F, but the universality of B-flat (even among hornists) makes flugabone the everyman’s weird brass instrument.

With that out of the way, here are some examples of flugabones being played at a high level. First up is Reginald Chapman’s group Bone Apple Tea Brass, which features multiple flugabones as the front line of the ensemble. This ensemble plays live in NYC and has an EP out on Spotify.

Next up is this German Brass recording (sadly audio only), the 3 trombone players are using flugabones. In the early days of YouTube, there used to be a live video of the German Brass performing this, and they appeared to be using Olds flugabones. I wish I could find that video again!

And here’s my own contribution, demonstrating one unique advantage you get from being able to play flugabone one-handed. This is from a live performance at the NAMM Show, and I’m using my King 1130. I have also used the flugabone’s one-handed ability to play flugabone with one hand while playing keys with the other, which I sadly don’t have any video evidence of (yet!).

Finally, if you’ve gone through all this and still want more flugabone content, here is a deep dive (over an hour long) on the flugabone, featuring a few excellent players and proponents of the instrument.

“Real” Bass Trombones

If you’ve gone down the trombone history rabbit hole at all, you’ve probably run across old bass trombones in keys lower than B-flat. While there is a lot of information scattered across the Web about these instruments, this is my attempt at summarizing the historical points and showing off some of the different kinds of long bass trombones that are out there, with my firsthand experience with a few of them thrown in.

The history is pretty simple. The trombone was invented in the mid-15th century, but brass instrument valves didn’t come around until the early 19th century. So for almost than 400 years, the only way to get lower notes was to build a physically longer instrument. Below the tenor trombone in B-flat, you had bass trombones, in G, F, E-flat, and other keys.

By the Classical period, the instrument had mostly settled on G or F. The G bass trombone was used briefly in France (along with C tenors and F altos), and at some point some of these instruments were imported into Britain. In France the G bass trombone (and indeed, the bass trombone in ANY key) did not last, but in Britain the G bass trombone flourished. In fact, the British G bass trombone tradition in brass band and orchestra lasted longer than anywhere else in the world, with G basses being regularly used all the way up to the 1960s. In continental Europe, the F bass trombone was the standard instrument for orchestras and military bands, though it was replaced by the Bb/F bass trombone much sooner than in Britain. Once the Bb/F bass trombone was invented, it spread like wildfire and (apart from in Britain) long bass trombones didn’t last very long.

Why is that?

Well, simply put, the Bb/F instrument was much easier to play. Trombones lower than B-flat are cumbersome instruments. The slides are too long to be able to reach all of the positions with just your arm, so they are equipped with long handles that allow you to reach the outer positions. But these handles are harder to use than just holding the slide brace directly, especially in fast passages. And on top of that, because the instrument is pitched lower, it is harder to play high and just more laborious in general. So when the Bb/F bass trombone came around, the long bass trombone’s days were numbered.

This isn’t to say that long bass trombones are impossible to play, or even difficult if you know how to play them. I personally love playing on the longer instruments, as they get cool sounds you just don’t get with a B-flat instrument, and I find the handle and lower pitches to be fun and rewarding challenges to overcome. Bass sackbut is one of my favorite instruments to play, and it is immensely satisfying to get right like all sackbuts.

The above image shows my British G bass trombone - a 1939 Boosey & Hawkes Artist’s Perfected. This is a British small-bore G bass trombone, and is a fairly typical example of the breed. The majority of British G bass trombones had very small bores (usually smaller than .490”), which matched the tenor trombones commonly in use in brass bands at the time. Because of the very small bore, these G bass trombones got a notoriously bright sound when played loudly, with people coming up with colorful things to say about it, such as it sounds like tearing paper, or that the G bass trombone is really a percussion instrument. In addition, because of the extra-long slide and the trombones’ position in the front row of parades (where the slides could be bad news for errant children running in front of the band), the G bass trombone earned the nickname “Kidshifter” in Britain.

A few larger bore British instruments were built for orchestral use, the most famous of which being the Boosey & Hawkes “Betty” model.

1939 Boosey & Hawkes “Betty” bass trombone in G, with attachment in D or C

This instrument had a relatively huge .5265” bore, and was much better suited for the modern orchestra than the narrow-bore brass band instruments, especially once large bore Conn trombones imported from the United States began to take over. The Betty models are rare and desirable today, and play nicely even with modern large bore tenor trombones. The attachment was pitched in D, but it came with an alternate slide to put the valve in C if you so desired.

(While the British G bass trombone tradition has long since evaporated, the general musical instrument maker Hakam Dim does claim to still offer a G bass trombone which appears to be based on an old small bore British design. However, I have not seen evidence of one apart from the single picture on their website, which appears to be a lifted picture of an original British G bass in a museum.

Meanwhile, in continental Europe, the long bass trombones (usually in F, but sometimes in E-flat or G) tended to be big and dark. An excellent example is this German F bass trombone I used to own, a Julius Rudolph from 1937.

1937 Julius Rudolph bass trombone in F

This instrument was just about the polar opposite from my small-bore British G bass trombone. It was all nickel silver, extremely heavy, and with the most drastic dual bore in the slide that I’ve ever seen: .510-.590”! It had a massive bell throat and sounded so huge that it sounded much closer to a modern F contrabass trombone than an F bass trombone. (This is also why I sold it…I wanted a real bass voice, and this instrument didn’t really give that to me.) It was made in 1937, which is very late for an F bass in Europe, but the manufacture of long basses did soldier on for a few decades after they fell out of favor in the orchestra, as they were still used in military bands and church trombone choirs (Posaunenchor).

Ideally, a truly modern long bass trombone would be somewhere in between the two extremes detailed above. No absurdly large throat, dual bore, or heavy weight, but also not a peashooter that only blends with similarly-small tenor trombones. I figured if I was to realize this dream I would have to get it custom built, but fortunately I ended up not having to, because I found this:

This is a German bass trombone in G, made by C.F. Zetsche & Sons in Berlin. Continental bass trombones in G are rare enough, but this one is a true unicorn. It has a .550” slide bore and a 10” bell - exactly the specs you would expect from a G bass built yesterday. It has a single valve in D-flat (not D!), with pull to C, allowing it to play fully chromatically. The slide is plated and has good action, and is totally usable with or without the handle. But more importantly than all of that, this instrument FEELS and SOUNDS like it was made yesterday. Apart from the physics of the longer slide, this instrument really isn’t any harder to play than my B-flat bass trombones, completely dispelling the notion that a longer instrument will always be difficult to play. This plays with the refinement and ease one expects from a modern bass trombone, in all registers. And the sound is…well, it’s a bass trombone. Not a bass trombone with an asterisk - just a great, modern bass trombone sound. It has a little bit of contra-ness in the pedal register with a big mouthpiece, but otherwise this is exactly how I would want a modern long bass trombone to sound. It’s perfect, and eventually I plan to have two independent valves fitted. But even as is I would be happy to use this in an orchestra.

Other modern G or F bass trombones are a rare thing, but a few do exist. Here is a brief overview of the ones I know of.

This first one is possibly the most well-known modern F bass trombone. It was made in 2004 by Yamaha as a surprise gift to Doug Yeo, who was the bass trombonist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the time. It has a full-length slide with seven positions.

This one is a modern instrument in F built by Gronitz, and while it originally had two valves (as seen on the picture on the right) it was later converted to a single valve. It has been for sale at the BrassArk for a long time now.

While there are no full-body pictures of this trombone, this gives you an idea. This is a modern bass trombone in F built by Josef Lidl, and later outfitted with independent Hagmann valves in C and D. It has a full-length slide with handle, and a .525” slide bore. It has been for sale at Swisstbone for years now, and is listed as a contrabass there.

This is a one-off bass trombone in F made by Matthew Walker of the world-class custom trombone maker M&W. It uses a lengthened 10.5” Bach 50BGL bell, a long .562” slide, and bass trombone rotors.

S.E. Shires, the popular modular trombone maker, used to offer the pictured conversion kit for their B-flat bass trombones that turned them into F bass trombones, complete with a long slide.

Likely the oldest instrument here (but still very much a modern instrument), this is a Holton bass trombone in E-flat with double slide. A few E-flat instruments with double slides were made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by a few makers, including Conn, Rudall & Carte, and the Salvation Army. Most were marketed as contrabasses, but some (like the Holton pictured here) were 100% bass trombones.

This is another rare continental G bass trombone - an East German instrument made by VEB. The “Great Bass” trombones in G made for Jeff Reynolds by Larry Minick are also worth mentioning, but those are really G contrabasses, rather than G basses.

Minick G “Great Bass” trombone

Personally, I think that modern long bass trombones have a lot more potential. It’s been a dream of mine for many years to have modern, double-valve bass trombones in both G and F, and to actually use them on appropriate repertoire. But they are a very niche interest, as even most bass trombonists have no interest in a lower bass trombone. With modern trombone-making techniques and the many stellar makers out there, I have no doubt that a modern G or F instrument could be a wonderful player with an incredible sound. (I also think that contrabass trombones in G, like the Minick above, deserve more experimentation as well.)

Bass Valve Trombones

While long bass slide trombones are much rarer than their B-flat counterparts, bass valve trombones in F (while still rare today) are much more common than bass valve trombones in B-flat. To my knowledge, B-flat bass valve trombones have only been offered by Thein and Jürgen Voigt (in cimbasso form), with the rest that exist being cobbled together from parts (such as the Robb Stewart “cimbassina”). Meanwhile, F bass valve trombone was the standard bass trombone in a few parts of Europe around the turn of the 20th century. The trombone section Antonín Dvořák had access to and wrote for used valve trombones, with an F bass on the lowest part. The one time Gustav Mahler wrote for bass trombone (his sixth symphony), he wrote for a valved F bass as that’s what was available in Vienna at the time. Bass valve trombones were also manufactured in E-flat, and while I haven’t heard of any made in G it is certainly possible. Drum corps trombonium bugles and cellophones, while not really bass instruments, are the closest thing I know of.

An important clarification is that the modern cimbasso is a contrabass valve trombone, not a bass valve trombone. Much like F bass and contrabass slide trombones, or B-flat tenor and bass trombones, both bass and contrabass valve trombones can be in F. Cimbassi have also been built in “straight” (valve trombone) form, but they are still contrabass instruments.

The Bartók Gliss

While the modern slide F bass trombones shown earlier in this article were constructed to utilize the full capability of a modern F bass trombone, quite a few modern F basses have been built specifically to play one famous glissando in the orchestral repertoire. This glissando occurs in Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, and is completely exposed with nobody else in the orchestra playing. It is a simple passage, glissing from B1 to F2 before the 2nd trombone continues the passage with another gliss. The reason why people have constructed new instruments for one glissando is because low B to F is not technically possible on a modern B-flat bass trombone. Bartok wrote the part for a bass trombone in F, and on that instrument the glissando is trivial - a simple 7th to 1st affair. But on a B-flat bass trombone, you have to come up with creative solutions to accomplish the gliss. As a fun aside, here are all the Bartok gliss solutions that I know of.

The easiest solution is to lip down from C to B, then gliss up as normal. This is what I did when I performed the piece, but that low B definitely doesn’t sound very strong when lipped down that far.

The most common choice is to start the gliss from low B with both valves, then at some point switch to just the F valve to complete the gliss. In my opinion this is the worst option and not even a real solution, as it produces a break in the gliss and does not achieve the composer’s desired effect.

A fun and effective solution is to pull the F valve tuning slide as far out as it will go, and then have the tuba player push the slide in as you ascend through the gliss. While the low B is sharp as most modern bass trombones do not have a long enough F pull to get an in-tune low B at the end of the slide, it is close enough for this excerpt, which is supposed to musically depict the composer vomiting (seriously!). Here’s a video demonstration of this solution:

Another fun and clever solution is to pull the F valve tuning slide as far out as it will go, and have a long string tied to the end of the valve slide with a ring at the other end. Wrap the other end of the string around your foot and use your foot to pull the slide back down as you ascend through the gliss. This might be my favorite solution that does not involve using a real F bass. Here’s a video demonstration:

The most expensive solution is to use a specially-built instrument designed to play that glissando in particular. There are two ways to go about this: either a B-flat bass with a special trigger mechanism allowing you to manipulate the valve slide while playing, or a real instrument in F. The B-flat method is less common, as this requires you buy or modify a B-flat bass trombone specifically for this purpose. Thein makes a dedicated Bartok model for this, and it has also been done as a modification to existing single-valve bass trombones.

Doug Yeo holding a double-slide Bartok F bass

As for real F bass trombones, several have been made for the Bartok gliss specifically. They are all double-slide affairs, sometimes with a matching bell sections and other times designed to mate up to a standard B-flat bell section. The most well-known example was made by Edwards, who rents it out for performances of the piece.

Of course, you could also use an existing F instrument to do the job, though most low F trombones are not F basses and thus don’t really get the right sound. Even so, because they are more widely available, players have used F contrabass trombones, B-flat contrabass trombones, and even F bass sackbuts to play the gliss. Regardless of what instrument is used, bass trombonists will usually only use the instrument for the glissando (along with the four staccato notes immediately preceding it), and then switch back to their normal instrument after.

I find it funny that bass trombonists have all sorts of solutions for “the Bartók gliss”, when in fact that single gliss in the Concerto for Orchestra is not the only low B to F glissando that Bartók wrote - there are many of them in The Miraculous Mandarin!

Piccolo & Sopranino Trombones

If the soprano trombone isn’t comically small enough for you, you are in luck! There are technically three smaller members of the trombone family, though two are so rare they might as well not exist. Welcome to the absurd world of piccolo and sopranino trombones.

Let’s start with the piccolo trombone. This instrument is pitched in B-flat, one octave above the soprano trombone, two octaves above the tenor trombone, and the same length as a B-flat piccolo trumpet. It is hilariously tiny, and despite the fact that renowned brass maker Thein offers one, it is not at all a serious instrument. In my opinion, soprano trombones are about the limit of real musical usefulness for a trombone, and an instrument an octave higher is only useful as a toy and curiosity. Still, piccolo trombone is a real thing that exists, so let’s talk about it.

As mentioned, Thein makes a piccolo trombone. I would assume they first made one for the German Brass, who often use the piccolo trombone as a “show instrument” according to Thein’s website. But they decided to make it a standard offering, and for whatever reason it was then copied (roughly) by at least one Chinese instrument factory and is now sold by Wessex Tubas and other Chinese retailers. It is typically marketed as a toy that happens to be a functional instrument, which I believe is an accurate assessment. Wessex states that their piccolo trombone is “the perfect gift for special occasions such as birthdays or Christmas”, and “ideal for the light-hearted brass musician in your life”. And indeed, generally people buy a piccolo to have around as a fun toy or conversation piece, rather than aspiring to use it as a serious musical instrument.

The availability of piccolos cheap enough to buy on a whim has resulted in this member of the trombone family being made and purchased far more than it really has a right to. To be fair, the same could also be said about the even cheaper and more-widely available Chinese soprano trombones. But more than anything, the piccolo trombone is a funny little horn and makes the world a little more whimsical.

The only other piccolo trombone I know of (apart from 3D-printed examples) is a one-off experiment that was made by the legendary brass technician Robb Stewart. He mentions in this article that he made it “more as a novelty or experiment” than a serious instrument, but says that it “actually does play well enough to be used in performances if used judiciously.” The article does not mention when he made this experimental piccolo, nor do I know when Thein started making theirs, but I would guess that Robb Stewart’s was first.

Robb Stewart’s B-flat piccolo trombone

The sopranino trombone has not enjoyed the same popularity as the piccolo or soprano. Quite the opposite, in fact; the sopranino is so rare that it is somewhat mythical. This is an instrument in between the soprano trombone and piccolo trombone in length and sound, sounding an octave above an alto trombone. In all of Internet history there have only been whispers of the sopranino’s existence, and we only have one video example of one being used: the famous all-trombone Peanut Vendor by the German Brass.

This video features 8 (!) different sizes of trombone, from contrabass up to piccolino. The piccolino trombone (in F, a fifth above the piccolo) was a gag horn made by Thein specifically for this bit, and unlike the piccolo it’s not fully functional. It can reportedly only play two partials, both of which are demonstrated in the video. Thein also made a page on their website for the piccolino, which makes one wonder if you can technically order one. Thein themselves refer to it as a “joke instrument”.

Two Thein piccolino trombones in F on the right, unknown other tiny trombone on the left

Anyway, that video also features the only known video evidence of a sopranino trombone being played. The sopranino in question was also made by Thein, and can be deduced to be in F (a fifth above the soprano, or a fourth below the piccolo) by the slide positions. (For those following along, here are the timestamps: soprano 2:19, sopranino 2:45, piccolo 3:21, piccolino 4:46.)

There are a few crumbs of evidence around the internet of other sopraninos’ existence. According to Robb Stewart, the famed brass maker and technician Larry Minick built a few sopranino trombones in E-flat using piccolo trumpet bells, including one for Jeff Reynolds, and they were apparently used in Jeff’s Moravian trombone choir in Downey, CA. I have yet to track down a picture of one. Moravian trombone choirs like those in Downey, CA or Bethlehem, PA are likely to be the only context sopraninos have been used in outside of the German Brass.

I remain a bit more optimistic about the potential of a sopranino trombone than I am about the piccolo trombone, but to me a truly useful sopranino trombone would have to have a (relatively) large bore and bell, to mirror the few large bore (~.500”) soprano trombones out there. The sound those instruments make is ALL trombone, big and dark. And I believe there is a bit of room to move that sound (not the small, trumpet-like sound of sopranos made with trumpet parts) upwards.

If you have any or know of pictures or videos of sopranino trombones, please do send them to me! I’m sure there is more information out there waiting to be found.

Trombones in C

The trombone family is very firmly based in B-flat. Modern tenor, bass, and soprano trombones are in B-flat, and the first contrabass trombones were in B-flat as well (with a few still made that way today). E-flat and F are the other standard keys - E-flat for alto trombone (though F altos do exist), and F for modern contrabass trombone. Anything else is much rarer. At one time G was the standard key for bass trombones in a few parts of the world (most notably Great Britain), and has also been used for a handful of modern trombones such as the Minick G “great bass” trombones made for Jeff Reynolds, and the Carol Brass CTB-2005-GLS-G-L soprano trombone in G. But apart from truly odd keys like D-flat and A-flat (both of which have had trombones made or modified to be in those keys), for a slide trombone the key of C is probably the rarest of them all. (We’ll discuss valve trombones later.)

Why is that?

You’d think that C, the most basic of all keys, would have a little more representation in the trombone world. However, since the trombone has been based in B-flat since its invention in the 15th century (though it was originally thought of in A due to different pitch standards at the time), there has been little demand for a trombone in C. There was a brief time where the standard trombone sizes in France were F alto, C tenor, and G bass, but the only lasting remnant of that time was the widespread use of the G bass trombone in Britain. France largely abandoned alto and bass trombones for a while, and the B-flat tenor became the standard there (like everywhere else). The result of all this is that there are very few trombones in C out there, and they are mostly regarded as odd curiosities at best. Additionally, most that do exist have a valve that puts the instrument in B-flat (and sometimes it is reversed so the instrument stands in B-flat), rather than fully embracing the key of C.

So what trombones in C do exist?

Possibly the most well-known example is the Conn 60H “Preacher” model. This instrument was built in the early 20th century, a time when many people in the United States played instruments at an amateur level and trombone parts were often written in transposing treble clef. Instruments like the 60H were built so that a trombonist could read from church hymnals, songbooks, and other music written in concert pitch treble clef.

Conn 60H “Preacher”, from a 1924 Conn catalog (scan from saxophone.org)

Conn 60H “Preacher” description from the same 1924 Conn catalog (scan from saxophone.org)

Although the 60H had a B-flat valve, not all C trombones built for its purpose (reading concert pitch treble clef music) did. H.N. White offered the King model 1125 in C, and according to the catalog description it was designed from the ground up in C rather than just being one of their B-flat designs cut down.

The modern equivalent to the Conn Preacher model is the Yamaha YSL-350C. This instrument was designed for young players who can’t yet reach 6th and 7th position, but still need a simple and lightweight instrument. To accomplish this, the YSL-350C stands in B-flat with the valve engaged, and pressing the trigger bypasses the valve to put the instrument in C. The C valve is then used for 6th and 7th position notes. Unlike the Conn Preacher, the YSL-350C does not have a slide long enough for 7 positions in B-flat, as it is designed to be used with the ascending C valve rather than exclusively in B-flat or C. So although this instrument is technically pitched in C, it is functionally a B-flat instrument and we think of it as such. The few other trombones with ascending C valves function in the same way (see my ascending valve article for more details), and I don’t count them as trombones in C as they stand in B-flat are designed to primarily play in that key.

Yamaha YSL-350C

Apart from the early-20th century C/Bb Preacher instruments and the ascending valve trombones (if you count them), slide trombones in C are extremely rare. Most that do exist are cut-down B-flat tenors, and I own one such instrument myself:

This is a 1979 Olds Recording R-20 tenor trombone, which has been cut down from B-flat to C. The valve attachment was also cut down significantly from the original F to become a minor-third attachment in A. This modification was made to fully commit to the key of C, rather than having a B-flat option or crutch. The slide gives 7 full positions in C, and its .495/.510” dual bore makes it feel similar to my Conn alto, which has a slightly smaller dual bore of .491/.500”. It has a neat sound roughly in between a (normal, small bore, B-flat) tenor and an alto, but leans a bit more towards alto in feel and sound when played with a small mouthpiece (which it prefers over larger pieces). But for all its alto-like characteristics, the R-20’s relatively large 8.5” bell helps it maintain a more tenor-like broadness to the sound, especially in the low register. With a smaller bell, it may very well be better described as a C alto rather than a C tenor.

My experience with this instrument leads me to wonder what a larger instrument cut to C would sound like. The R-20’s design lends itself well to a more alto-ish experience, but perhaps an orchestral tenor trombone would keep a more tenor-like character. The R-20 is a fairly unique design to begin with, so a more mainstream design might give different characteristics.

Conn 36H alto trombone in E-flat (top), Olds R-20 tenor trombone in C (middle), Willson 311TA tenor trombone in B-flat (bottom); all with minor-third attachments

Another thing I’ve noticed with this instrument is that a C tenor trombone slide might just be the perfect length. On a B-flat tenor, 7th position is far out enough that most people have to contort their body to reach it. It’s a big reason why trombonists tend to avoid 7th position most of the time. An alto has the opposite problem; the slide is short enough that it’s easy to accidentally overshoot 7th position and take the outer slide completely off. On C tenor, 7th position is roughly where 6th position is on a B-flat tenor, which is reachable with a fully outstretched arm without any contortion necessary. There is no danger of overshooting, and no discomfort necessary to play all 7 positions. Additionally, the slide positions feel closer to tenor positions than alto positions, meaning fine pitch adjustment is easier and the whole instrument feels more stable. Of course, human arms come in many different lengths, so no commentary on trombone slide length will be a universal experience. But for me at least, tenor C might be the Goldilocks slide length.

Recently, the Swedish maker Lars Gerdt added a tenor trombone in C to their lineup, the model 316:

Lars Gerdt model 316 tenor trombone in C (image from gerdt.se)

This trombone has a .500” bore, a 7.9” bell, and tuning in slide. As far as I’m aware, this is the only currently offered trombone in C as a standard model (rather than a custom order). Lars Gerdt offers quite a few other interesting brass instruments as well, including the model GS contrabass trumpet.

In contrast to the modern instruments above, here is a very old and very weird trombone in C:

This instrument was built in 1850 and is in high pitch C. It has no markings and I have no idea why it was made, but its owner has said that it is a great player.

Apart from the rare C tenor trombone, there have been a handful of contrabass trombone in C. The most modern example is the Miraphone 670 CC:

Miraphone 670G in C (image from hornguys.com)

The Miraphone 670 contrabass trombone is usually a single valve instrument in B-flat, in the style of the famous Conn B-flat contra. In this form it is…not a good instrument, to put it lightly. Steve Ferguson of the Horn Guys wrote to Miraphone one night suggesting a version of the model in C with 2 valves, and Miraphone made it. It is reportedly a big improvement over the B-flat model, but I haven’t played one myself.