All the Brass Instruments I've Ever Owned

Over the years, I have owned over a hundred brass instruments. I thought it would be fun (both for me to write, and for the reader to read) to show all of them in one place and give my thoughts. Enjoy!

Horns

Alexander 202ST

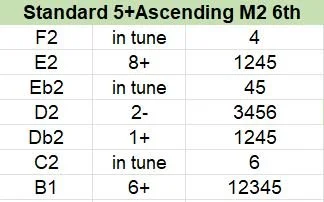

This is one of the coolest instruments I’ve ever owned, and possibly the best player out of all of them. It’s an Alexander 202ST, which is a compensating double horn with a stop valve and, most importantly, an ascending 3rd valve in the French style. This particular instrument was made for a Parisian player, and it is an exquisite instrument. It’s the kind of instrument I never thought I would own, but here we are! I traded my double descant horn for this, and I couldn’t be happier. The ascending 3rd valve fingerings take a little while to get used to, but the payoff is worth it!

1990 King 2270 Eroica

This horn exudes the old-school Hollywood horn sound. It has a massive bell throat that is even larger than a Conn 8D’s throat, and is extremely free-blowing. Designed by George McCracken, the Eroica is known for being one of the most open-blowing horns of all time and having a huge sound. The Eroica never caught on as a desired horn for professionals like the Conn 8D or Alex 103, but it is a wonderful horn nonetheless and I was able to acquire it for cheap thanks to its relative obscurity.

Yamaha YHR-321

This is a single Bb horn with stopping valve, and is one heck of a sleeper. Yamaha has a habit of making instruments they market as student models, but are secretly pro-quality gems, and the YHR-321 is no exception. It is a copy of the Alexander 90, a professional single Bb horn historically played by many professionals including Dennis Brain. The light weight and easy high range make this horn a good descant horn substitute for a fraction of the cost.

Selmer Thevet Ascendant

This is a true French horn, built by Selmer Paris as one of the last examples of the French tradition of small bore piston horns with ascending 3rd valves. I’ve dreamt of owning one of these for many years, and while it is not yet in playing condition I am so thrilled to now own one. These are extremely rare and command collector prices, but thanks to the severed leadpipe I managed to snag this one for an unfathomably low price.

Cerveny Vienna horn

This is a single F Vienna horn made by Cerveny, likely in the late-19th century. As you can see it is currently in project shape as it is missing the pumpenvalves. But I will eventually get new valves made for it so I can finally realize my dream of having a (working) Vienna horn!

E.F. Durand WH960B Wagner tuba

This is a Chinese compensating double Wagner tuba, made by Jinbao. These are reasonably affordable new, but I got this one for an absolute steal!

Dynasty M546 high F marching horn

Marching French horns are usually in B-flat, or G in the case of the drum corps French horn bugles. But there have been a few marching horns made in high F, including by Kanstul, Dynasty, and Blessing. I never quite understood the point of high F marching horns, as the Getzen frumpet proved that a bell front instrument the length of a mellophone with a French horn mouthpiece is usually not a good idea. I needed to try one out for myself, so when I had the opportunity to trade an instrument I didn’t need for this Dynasty M546, I took it.

I think my wariness was well-placed, because the M546 is just okay. It sounds like the weird stepchild of a horn and a mellophone, only retaining the worst parts of both. It plays and sounds much better than a frumpet (which isn’t saying much), but it’s still nothing to write home about. Like the frumpet, I think this instrument would benefit from using any mouthpiece that’s not a horn mouthpiece, so a receiver swap may be in this horn’s future.

Hampson Horns/Jackalope Brassworks corno da tirarsi

The corno da tirarsi, a.k.a. slide horn, is a very rare and unique instrument that J.S. Bach wrote for. I am fortunate enough to own this wonderful modern slide horn, which can be crooked to Bb, A, Ab, or G. It has a lovely sweet sound and is an impeccably-built handmade instrument. I used it extensively in my latest Christmas multitrack.

1975 Holton Farkas H180

This Holton double horn had a hard life in a school inventory, but my tech resurrected it from scrap condition back to a playable instrument. It’s certainly not the best horn out there, but it’s not the worst either!

1980s Holton H200 double descant horn

The Holton H200 is a copy of the famous Paxman model 40, and was also sold as the Conn 12D. These are great double descants for a much more affordable price than a Paxman or Alexander. I got this one for a steal in nearly new condition - it had barely ever been played! Though I enjoyed playing this instrument, I found that I actually prefer the feel of a good B-flat horn in the very high register over the feel of the high F horn on this double descant, so I eventually traded this horn for my Alexander 202ST compensating double horn with ascending 3rd valve.

1947 Conn 6D Artist

This is a 6D from the era where it was a top-of-the-line professional instrument, long before it became an intermediate horn meant for schools. As such, it has the quality and sound you would expect from a pro-model Elkhart Conn. Unfortunately, most 6Ds this old have had bell transplants due to the original bells getting damaged beyond repair, and this one is no exception. The bell looks to be an early Abilene bell, probably from a 4D student model. It’s a shame the horn lacks its original bell, but despite the transplant it still plays and sounds fantastic. This is the second early 6D I owned, and I used it extensively during the year and a half I owned it.

1938 Conn 6D Artist

This is the first early 6D that I owned, and it was my only double horn for awhile. Despite its totally worn-out valves, it was still possible to make it do your bidding and it had a special sound. I kept it around after getting another horn in hopes of eventually getting it restored, but money dried up and I had to sell it before I got the chance.

1936 Buescher 330

This is a license-built copy of the famed Alexander 103 double horn. It had the sweetest sound, but unfortunately the rotors were badly in need of a rebuild for it to be usable, so I sold it to a Buescher collector.

Josef Lidl double horn

This is a cool double horn made in the Czech Republic, which I bought from Ukraine. It was very heavy physically, but played very well with a nice sound and no issues. It stayed with me for awhile, but I eventually sold it on.

1971 Holton Farkas H178

Nowadays, Holton Farkas double horns are a common sight in high schools, and generally have a reputation for being student-level instruments. But a good one is every bit a professional instrument, and that’s doubly true for the early ones such as this one from 1971. This is the horn I replaced the derelict 1938 6D above with, and it was my only horn for quite a few years before being replaced by my King Eroica. This particular H178 was an exceptional example of the model, and every horn player who tried it loved it. However, the yellow brass medium-throat bell was neither fish nor fowl to me…the sound had none of the qualities of both small-throat (a la 6D, 103) or large-throat (a la 8D) bells that I love. Instead it languished somewhere in the middle, and I was never able to achieve a sound I was truly happy with on it. It was a solid workhorse, but I was happy to replace it with the Eroica.

1977 Holton Farkas H180

Like my 1975 H180, this horn had a hard life in a school inventory, and was brought back to life by my tech. I eventually traded it for the Dynasty M546 high F marching horn listed above.

Holton MH101

This Bb marching horn has to be one of the most Seussian instruments of all time. Its specs are just as odd as its looks, too; it has a tiny bell throat and a trumpet shank, the latter of which allows you to use a whole variety of mouthpieces with it. With a horn mouthpiece and adapter, it’s a decent little marching horn. But the other mouthpieces far more interesting. Despite being pitched a 5th lower, this horn could scream better than most mellophones with a marching mellophone or trumpet mouthpiece. It is a truly hilarious instrument, but at the end of the day I absolutely didn’t need it for anything, so off it went.

Getzen 383 frumpet

This doesn’t really belong with the horns, but it doesn’t really belong anywhere else either and it takes a horn mouthpiece so I’m putting it here. Anyway, if you’re reading this you probably already know about the frumpet. It is awful. Don’t buy one, no matter how cheap…unless you just want to use the valve block for parts.

Schiller Field Series Elite Bb marching horn (not pictured) - I briefly owned this Yamaha YHR-302MS clone, and it was exactly…ok. Not great, not awful. It was given to me for free, and I gave it away for free.

Trumpets

Yamaha YTR-737

This is my workhorse trumpet, and is the only trumpet to leave the house with very rare exception. It was made in the late 1970s, during a period where all of Yamaha’s professional trumpets were designed in collaboration with Renold Schilke. Some, including mine, were even assembled in the Schilke factory! The result is these horns play pretty much like Schilkes, for a fraction of the cost. The YTR-737 in particular is essentially a Schilke B5 with Yamaha written on it. This horn is excellent for the commercial work I do on trumpet. If I ever start getting classical trumpet gigs, I may need to acquire a darker-sounding Bach-style Bb, but until then the 737 does everything I need.

Selman 17001

I’ve owned this Chinese C trumpet for a long time, even longer than the YTR-737 above. I got it on eBay for $85, and it has exceeded my (low) expectations from day one. It is a perfectly competent C trumpet. Not perfect of course, but really no C trumpet is and the quirks this one has are very manageable. It also doesn’t have the sterling sound of a nice Bach or Yamaha Xeno, but for what I need C trumpet for (mostly just my own multitracks) it is completely fine. Sure, it would be nice to get a better C eventually, but why spend 4 figures when this $85 horn is decent enough?

JinYin JYTR-A688

This is a Chinese Eb/D trumpet that has same story as my Selman C trumpet above: I got it used for very cheap on eBay, I had low expectations, and the horn exceeded all of them. Again it is not perfect, but it genuinely plays very well and has a nice, light sound. For an instrument that I will literally never need, a really cheap one was the only way I was ever going to own one and this JinYin is good enough that it is a viable option in my arsenal.

Bach 351G alto trumpet

This is one of the coolest instruments I own - a Bach F alto trumpet with a gold brass bell. The Bach alto trumpets were built in very small numbers up through the early 2000s, in both F and E-flat. They are very rare and probably the best alto trumpets ever made. This one is in mint condition and plays like a dream. This is 100% a forever horn!

J. Melich Eb/D bass trumpet

This rotary bass trumpet is also a fairly recent acquisition, and replaced my Bb rotary bass trumpet. It is old and worn, but it has a fantastic trumpet sound and plays very well throughout the whole range of the instrument - down into the pedal register and up through sounding Gb5, the highest note in the repertoire.

Mendini MPT-N pocket trumpet

This Chinese Amazon-special pocket trumpet was a Christmas gift, and I love it because it is small enough to keep on my desk and noodle with whenever I feel like. I have actually used it on a gig before though - it was the perfect instrument to pull out for a Raymond Scott composition called “The Toy Trumpet”. It is a decent little trumpet - nothing spectacular, but there’s nothing actually wrong with it either. It just…exists. I also find the left hand grip and 3rd valve kicker to be more comfortable than they are on normal trumpets.

1968 Conn 8B Artist

I never actually took a picture of this horn by itself, which is surprising considering it was my main trumpet for quite a few years. I bought it for $50 via Craigslist from a farmer in the middle of nowhere in Illinois, who had used it as a wallhanger for 50 years. Looking back on it, I really should have prioritized finding a better Bb trumpet sooner, as it really wasn’t an instrument I should have been gigging on. The valves were worn, it was hard to play, and I never got a sound that I really liked on it. When I finally got my Yamaha YTR-737, I realized just how much the 8B had been holding me back.

1965 Conn 6B Victor

I got this years after selling the 8B, entirely because I was curious what a trumpet with the same basic design as the 8B but in much better condition would be like. I still didn’t like it very much, but it was definitely a better player than my 8B had been. I sold it on pretty quickly.

Carol Brass CTR-2000H-YSS

Another horn that I owned and sold long before I started taking pictures of all my instruments, this student-model Carol was my first Bb trumpet, naturally bought for cheap on eBay. It was…almost decent. I definitely wasn’t great at trumpet back then, but the trumpet felt harder to play than even the Conn 8B that I replaced it with. I gave it to my grad school roommate before I moved to LA.

Holton LT101

The LT101 is a fairly rare lightweight copy of a Bach 37 with a 25 leadpipe. I got this one for very cheap from a friend, and was interested to see if I took to Bach-style trumpets any better than I had when I owned the Carol trumpet above. Despite the fact that this LT101 was a good player, the answer was a resounding “no.”

Josef Lidl Bb bass trumpet

This was my first bass trumpet, which I replaced with my current Melich Eb/D. It was decent and had a real trumpet sound, which is why these Lidls are the gold standard cheap bass trumpets amongst trombonists. But it had plenty of challenges, and my Melich Eb/D bass trumpet played circles around it in every register, so it was an easy decision to sell it off.

Mollenhauer low Eb trumpet

This was a true orchestral low Eb trumpet. Not an alto trumpet or bass trumpet, but a proper long Eb trumpet like the Heldenleben parts were written for. It had a totally different sound that was much closer to a baroque trumpet than a modern one. But it was also very hard to play and had woeful intonation, and though I did manage to sneak a few stems of it onto a TV commercial, it didn’t last long before I sold it. I would love to own a long orchestral trumpet again, but it would need to be a better-quality instrument in F.

Cornets

Yamaha YCR-2310

This is my current cornet, and by far the best-sounding and playing out of all the Bb cornets I’ve owned. The YCR-231 and 2310 are interesting sleeper models, because although they don’t have Shepherd’s crooks, they have large bores and properly large British-style bell throats. The result is that they have a real, dark, beefy, British brass band cornet sound, despite looking like American cornets. Their Shepherd’s crook stablemates, the YCR-233 and 2330, were actually built with more American specs and sound brighter. A nice upside of this mix-up is that the 231/2310, which looks like yet another worthless student cornet, can be bought for next to nothing. I have used this instrument in a ragtime orchestra and in my multitracks, and have no complaints.

DEG/Dynasty 1220

This is an alto cornet in F, made for Dynasty by Willson. The 1220 was marketed in the United States as a “marching alto/French horn”, whatever that means, but is all cornet. These are great players, as you would expect from Willson. Not without quirks, but a totally manageable, giggable, and recordable instrument. This particular 1220 is a later example, branded Dynasty and with the largest bell I’ve seen on one at 7.5”. It’s the second 1220 I’ve owned, and plays wonderfully!

DEG/Dynasty 1220

This is the first 1220 I owned, which was an early example with the small 6.1” bell and circled DEG lettering on the bell. I used it a ton while I had it, but I ultimately sold it during a rough financial patch. Took a few years for me to get another one!

1964 Olds Ambassador

This cornet was decent. It was a nice player and well-built like all Ambassadors, but the sound was too bright and trumpety for my tastes, even with a deep Wick British cornet mouthpiece. That said, it was still a significant upgrade over my Bach CR310. The thing about student-model cornets is that they are basically worthless as they’re not used in schools anymore, so you can get a nice playing cornet for next to nothing. I found both this and the Yamaha above on eBay, without much searching, for about $50. So if you are looking to add a high brass instrument to your stable on a small budget, I would recommend looking for a student cornet rather than a student trumpet. With an American cornet mouthpiece it sounds like a trumpet, and with a British cornet mouthpiece it has a sweeter, mellower sound.

Bach CR310

I’ve had this student-model cornet (which is a Bundy in all but name) for a long time. It was my first high brass instrument, and I used it heavily in my 2013 Christmas multitrack. I’ve spent a lot of time with this thing, and…it’s not very good. It is currently in the shop having some mad science done to it in order to turn it into something entirely different, which is really the only way forward.

Flugelhorns

1972 Conn 24A flugelhorn

While stamped Conn on the bell, this instrument was manufactured by Willson in Switzerland. I was very surprised with this instrument. It has a dark, velvety flugelhorn sound that is very similar to my old Couesnon, but at the same time sounds clearer and more modern. It is also much easier to play than the Couesnon was, particularly in the high register. It is a great flugelhorn, and sounds better than many modern flugelhorns that I’ve tried. The excellent Bauerfiend pistons don’t hurt either! The only downside is that bell throat is so large that my H&B flugelhorn mutes don’t fit.

1890s Lyon & Healy “Silver Piston” flugelhorn in C

This adorable little C flugelhorn is only a little bigger than a pocket trumpet, and is a true antique from the late 19th century. It is in high pitch, somewhere between C and D-flat, and while it does need some work (there is a leak somewhere in the 1st valve circuit), the valves are fast and it has a sweet sound. It has an odd shank though, closer to a trumpet shank, and none of my mouthpieces are a great match for it. A safari is needed!

Couesnon flugelhorn

This pre-WWI Couesnon flugelhorn was one of my most-played instruments for about 10 years. Being so old, it was definitely not as easy to play as a modern flugelhorn, even with the GR/Melk leadpipe I had installed. But the luscious sound was very special, and it only cost me $300 plus the cost of the Melk pipe installation. When I got the Conn flugelhorn above, I couldn’t decide which one I liked better so I left it up to a friend who was in the market for a flugel to decide. She chose this Couesnon, so it now belongs to her and I kept the Conn.

Elkhart alto flugelhorn

This alto flugelhorn is in F, with Eb slide. It is stamped Elkhart, but was made by Couesnon. It was a perfect match to my Couesnon flugelhorn in both sound and feel, and was one of the easier-to-play weird alto brass instruments I’ve owned. But it still had its quirks, and I later acquired a Kanstul KMA-275 marching alto in F that, while technically not an alto flugelhorn, did the alto flugelhorn thing even better than this actual alto flugelhorn. So, I sold it off.

G Bugles

Dynasty G350A soprano bugle

The Dynasty 3-valve soprano bugle (essentially a trumpet in G with a large bore and bell throat) went through a few variations over the years. Some were made by Allied Supply in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, while others were made by Weril in Brazil. The G350A was made by Allied before 1993. Soprano bugles were known to be screamers, and the G350A is no exception. But its secret weapon is its fat sound in the low register; with the right mouthpiece, it is an excellent alto trumpet in G. This is mostly how I used it when I owned it - you can hear it used in this way in my Way Away multitrack.

King K-40 flugelhorn bugle

This is a very unique piece of drum corps history. It began life as a stock, 2-valve King K-40 flugel bugle in G. At some point in its life, Ken Norman added a rotor valve to make it fully chromatic. The rotor lowers the pitch by a minor third - aka a standard 3rd valve - and the result is a 3-valve G flugelhorn, but in just about the weirdest possible configuration. It is absolutely playable, but the 3rd valve being in the left hand obviously takes some of getting used to. The K-40 has a trumpet mouthpiece shank, and with my Denis Wick 5 alto horn mouthpiece it has a gorgeous, sweet sound. Despite being possibly the most cursed flugelhorn to ever exist, it also legitimately has one of the most pleasing sounds out of all the flugelhorns I’ve owned or tried. I plan to take Ken’s modifications a step further by swapping the 2-valve section for a Kanstul 3-valve G bugle section (which should drop right in). After extending the 4th valve circuit down another whole step, I’ll have an amazing-sounding 4-valve G flugelhorn.

King K-50 mellophone bugle

Arguably the most legendary mellophone bugle of them all, the 2-valve K-50 is the sports car of mellophones. The bright, crystal clear sound and effortless high register make the K-50 a weapon in the right hands, and up in the stratosphere the lack of a 3rd valve isn’t an issue. I had a blast with mine, and would have kept it if money permitted. Though I have an amazing 3-valve Kanstul 180 mellophone bugle now, I miss the K-50 and its intoxicating high range. That sound and feel sticks with you forever!

Olds Ultratone BU-06 mellophone bugle

This is a piston/rotor G mellophone bugle. I have even less use for P/R bugles than I do normal 2-valve bugles, but it is kind of fun to exercise your brain with both valves on your thumbs. Anyway, I bought this one because it was very cheap and in great shape, and I have a dastardly idea on something nefarious to do with it. Let’s just say it’s not going to remain stock for long. :)

Kanstul KMB-180 mellophone bugle

This is possibly the G bugle I’ve always wanted the most, especially after I owned and sold my KAB-175 alto bugle (seen below). When I saw this one come up for sale at a very reasonable price, I snapped it up. It is certainly showing its miles, but it still has it where it counts. It has a good dosage of that K-50 magic, including that clarity of sound that makes F mellophones almost feel muffled in comparison. It’s also a lot more useful than a K-50 thanks to the 3rd valve. I’m keeping this one forever!

Kanstul KAB-175 alto bugle

The alto bugle is a mellophone bugle with a much smaller bell flare, and while it was much less common than the mellophone or French horn bugles, it did see use in DCI. This early pattern Kanstul KAB-175 is legitimately one of the best instruments I’ve ever played. It was so easy to play, to the point where it was addicting and very difficult to put down. Yet despite this, I ended up selling it because the sound it made (in between a mellophone and a trumpet) was pretty useless. Out of all the instruments I’ve sold, this is the only one I regret selling.

Dynasty III alto bugle

This alto bugle was built for Dynasty by Willson, and is a very different instrument than the Kanstul alto bugle above. This one played and sounded like a big flugelhorn, and despite some odd intonation quirks was a very good instrument overall. It is also one of a handful of brass instruments I’ve owned where there is only one known example in the world. Before I found it on Canadian eBay and bought it, there was no evidence on the Internet of this particular model ever existing, and we still don’t know if any others were made.

Kanstul MFL meehaphone

The meehaphone is the most legendary G bugle of them all. Built for and used by the Blue Devils from 1987 to 1991, it is essentially a field descant horn in G. There is only one meehaphone in the world in private hands, and for awhile I was lucky enough to be the owner. I sold it mainly because, while extremely cool, the meehaphone didn’t have a special sound and wasn’t a great player. Still, I feel very privileged to have owned it.

Olds Ultratone BU-10 French horn bugle

This is one of two Ultratones I’ve owned. I don’t really have any interest in piston/rotor bugles, and least of all these long model French horns (which in my opinion look pretty hideous), but this one was selling for pocket change so I figured at the very least I could use the bell for a silly project. I was surprised to learn that this horn is a great player, sounds like a concert horn, and is easier to play (especially in the high register) than the 3-valve Kanstul 185 below. It’s kind of awesome. And while it is useless in its configuration, the sound and feel are good enough that I now want to have it cut to Bb and get a proper valve section installed.

Kanstul KHB-185 French horn bugle

Here’s another rare bird! By the time 3 valves were legalized in DCI in 1990, the French horn bugle was already an endangered species, and few 3-valve French horn bugles were built. Only 14 of these KHB-185s are known to have been made. It was a fabulous instrument, and may be the closest thing to a true horn sound from a bell-front instrument that’s ever been made. I loved it. I sold it in favor of the low alto bugle below, because with a horn adapter and a horn mouthpiece, the low alto could do the same thing while also having all the other available mouthpieces available.

Kanstul low alto bugle

The low alto bugle is essentially the Kanstul KHB-185 French horn bugle above, but with a trumpet shank. Only 6 were made, and they were used by the Mandarins in DCI. I got this one on eBay for about $100, with a crunched bell and listed as a marching baritone. It’s one of those instruments that I never thought I’d get to even see, let alone own. I’ve been fortunate enough to have many such instruments come through my collection, mostly via eBay. I really enjoyed playing the low alto, especially as the trumpet shank allowed for many different mouthpiece possibilities (like the Holton MH101 Bb marching horn) and the low alto somehow played great with all of them. I held until the low alto the longest out of my G bugles because it played well, made different sounds than anything else I had, and was just a really cool thing to own. But it too eventually got sold off because I had nowhere (other than my own multitracks) to use it.

Kanstul KBB-190 baritone bugle

In my opinion the best of the G baritones, this is an instrument that I would look at on the Kanstul website and dream of owning as a high schooler. (I’ve always been a nerd, what can I say?) Like all of my other G bugles, I found this for cheap on eBay. It was a wonderful player, with a huge yet colorful sound that distinguished it from any Bb marching baritone. But, like all the other G bugles, I eventually just couldn’t find a reason to keep it when there was no real use for it…not to mention that I already owned a flugabone, a British baritone horn, a marching baritone, and a euphonium.

Mellophones

Yamaha YMP-204MS

The Yamaha 204 needs no introduction - it is the gold standard of all mellophones. It’s not perfect, but it is SO much closer to perfect than most other mellophones. While this 204 isn’t the prettiest, it’s got it where it counts and is my workhorse mellophone for both live gigs and recording. The only reason this would ever leave my stable is if I lucked into a cheap 204 in nicer condition...and even then, I might still keep this one around as a backup.

1969 Conn 16E

This is the instrument that started my obsession with obscure brass instruments. I bought it on eBay in 2011, shortly after graduating high school, and it was my gateway drug. I still have it and use it on all my videos, and it’s not going anywhere. Despite its many flaws, this mellophonium is still my desert island horn. I will always love it!

Holton M602

The M602 was Holton’s second mellophonium model, after the more traditionally-designed M601. Holton marketed the M602 as a “marching mellophonium”, and it really does feel like an instrument that pulls from both mellophoniums and marching mellophones, which were both around at the time. It has the sound and feel of a mellophonium, but with the bore and ergonomics of a marching mellophone. In some ways it’s the best of both worlds, and it really does have a special sound. It is darker than the Conn 16E and perfect for smoky jazz. Do I need a darker mellophonium? Not really…but this is one of those instruments that I want to hold on to, and it’s not worth enough to be worth the effort of selling anyway. So this one is probably staying with me!

Yamaha YMP-201E

The YMP-201 (no M) was the first Yamaha mellophone. It also has the distinction of being the last circular mellophone design, and is arguably the only one that really feels like a modern instrument. It was designed for use in Japanese school bands in the late 1980s, as a cheaper alternative to the French horn (which was prohibitively expensive in Japan at the time). It really plays fantastically well and is a beautifully simple and functional design. However, using the 201 in a big band exposed the circular mellophone’s greatest disadvantage: the downward-pointing bell made it impossible to hear myself at all. I’ve owned two of these, and had sworn off circular mellophones after I sold the first one. But I traded my first 201 to my repair tech, and he took it and straightened the bell, turning the instrument into a mellophonium. That made me realize that I wanted to do that as well - to make this great instrument into something actually useful (well…relatively!). So I bought another one, and had my tech turn it into the beautiful mellophonium you see here! It is a wonderful instrument with a lovely, unique voice.

Kanstul KMA-275

This is a rare small-bell variation on the marching mellophone called a marching alto. Apart from the size of the bell flare, this KMA-275 is the same instrument as Kanstul’s late-pattern marching mellophone, the KMM-280. The marching alto and marching mellophone have the exact same relationship as the alto bugle and mellophone bugle. Much like the alto bugles I’ve owned, the 275’s smaller flare makes it lose much of the characteristic mellophone sound. However, unlike my Kanstul 175 alto bugle that was far too flat when using a tenor horn mouthpiece, the 275 will happily play in tune with a tenor horn mouthpiece, giving it a dark alto flugelhorn sound. This sound is so flugelly, in fact, that I sold my actual alto flugelhorn shortly after acquiring the 275. It’s also just an excellent instrument in general, with solid intonation, good ergonomics, and a main tuning slide kicker to let you fix any note on the fly. I sold this instrument to a friend, as I found that I prefer my Holton M602 mellophonium for alto flugelhorn duties.

King 1121

The 1121 is what replaced the 1120, and is an incremental improvement. The most notable differences are the angled leadpipe, spring-loaded first valve slide, and re-wrapped 3rd valve slide. I bought this one cheap mainly to compare it to my 1120, but once I got my Yamaha 204 the 1121’s days were numbered. I eventually sold it locally to a friend.

1993 King 1120

This became my workhorse mellophone the second I bought it in 2023. Its position was usurped by my Yamaha 204M, and I eventually sold it to a friend. Still, it was a solid mellophone that was very easy for me to acclimate to after owning its father and grandfather, and I can heartily recommend the 1120 to anyone looking for a good marching mellophone for cheap. It is by far the best mellophone that is readily available for less than $200 on eBay, and it served me very well.

Nirschl E102SP

This rare mellophone is the worst mellophone I’ve ever owned. It is so bad it may even be worse than the abysmal Getzen frumpet. Seriously…don’t buy one.

Yamaha YMP-201M

This was my first marching mellophone, acquired in 2022 after over a decade of owning pretty much every other variation of mellophone out there. It was a pretty good instrument, and I used it a fair bit before acquiring my King 1120. The reason I ultimately bought the 1120 and sold the 201M was because the 201M felt very tight and unforgiving to play, and I got tired of dealing with that quickly. It’s a shame because it had a lovely sound that, in some ways, was better than the newer models. But ultimately, there are good reasons why the 201M became the 204M.

Yamaha YMP-201

This was my first 201, which allowed me to discover how good circular mellophones could be. The one I own now is in better shape cosmetically than this one was, but they both play/played beautifully.

1925 Buescher 25 True Tone

This circular mellophone (in F) has two rotary change valves. One puts the instrument in Eb, the other puts it in D, and both together put it in C. Despite this 25 having worn-out valves consistent with an instrument this old, it was still a great player with a gorgeous, velvety sound - much darker than any of my other circular mellophones. It played well in all 4 keys, and had a unique sound in each.

1930 Conn 8E

The Conn 8E is a ballad horn in C and B-flat. While some ballad horns from the era were more like circular tenor flugelhorns, the 8E was a circular mellophone crooked in C by default with a slide to B-flat - essentially, a tenor mellophone. I enjoyed playing it, and the slanted valves did a lot to improve the usually-terrible circular mellophone ergonomics. It wasn’t the easiest instrument to play, as it felt pretty different from most other instruments (even other circular mellophones in higher keys). But after a short adjustment period each time I picked it up, I found myself unable to put it down. It felt, played, and sounded like an extra-large-bore single C or Bb horn, which I suppose isn’t far off from what it was. A ballad horn, and in particular a Conn 8E, was one of those instruments that I dreamed of playing but never thought I would even get to see one, let alone own one considering the collector prices they usually go for. But one day on eBay, there it was at a shockingly affordable price. When I owned this it was the crown jewel of my collection, and every time I showed it to someone I had a silly grin on my face. I couldn’t hide my passion for this instrument. I didn’t think I would ever sell it, but my brief flirtation with being a collector (at the time I owned 8 mellophones…) eventually wore thin. I’ve never really been a collector, as I hate having instruments I never use. So I eventually let the 8E go. I don’t regret selling it, but I do look back on my time with it fondly.

1918 Conn 6E

This E-flat only mellophone was marketed as a “French horn alto”, in reference to its wider, horn-like wrap compared to the more tightly-wrapped Conn 4E. But it was all mellophone, and also the same exact design as the 8E ballad horn above, just in E-flat instead of C. This instrument had a more familiar feel, and had a gorgeous, colorful sound - probably my favorite sound out of all the circular mellophones I’ve owned. But the valves were worn and I just didn’t need it (like all the other circular mellophones), so off it went.

Alto & Soprano Trombones

Conn 36H alto trombone with C valve

The Conn 36H usually has a Bb attachment, but this one has had the attachment tubing cut to C. The valve is the stock Conn rotor, and the valve tubing is the same .500” bore as the lower leg of the slide. The C attachment really makes perfect sense on an alto trombone - to me trill valves are gimmicks, and you really don’t need a Bb attachment when alto trombone repertoire never goes below low A. The C attachment is the most practical tuning for an alto trombone valve that I’ve encountered, and the alto it’s attached to is a wonderful instrument that is addicting to play.

Unmarked German soprano trombone

This is undoubtedly one of the coolest brass instruments I’ve owned. This unmarked instrument was likely an exam instrument made by a German brass-making apprentice, and is handmade and the highest quality. It has an old-school leather strap to activate the valve, 4 different slides for the valve that allowed you to tune the valve to A, Ab, G, Gb (via pull), or F, a nickel bell kranz, and about 5 positions on the slide. This instrument is likely the only one of this specific design in the world. With the right mouthpiece it had a real trombone sound, and it was a great player. I sold it because I had no real use for a soprano trombone…and because I got GOOD money for it.

Selman 11303N alto trombone

Somehow this is the only picture I could dig up of this basic nickel-plated Jinbao clone of a K&H Slokar alto trombone. These Chinese Slokar clones used to be EVERYWHERE, as they were the only option for an affordable alto trombone to learn on. Nowadays quite a few retailers who used to stock the Slokar clone no longer do, and there are other cheap Chinese options now. But back in grad school when I owned this, it was this or pay big bucks for a “real” alto. While it obviously was far from perfect, the Selman was good enough to learn on and play the occasional gig with. For the price, I really had no complaints.

Tenor Trombones

1970 King 3B

This is my workhorse tenor trombone, and has been since I bought it in 2015. It sounds great, plays great, can cut through anything, will work with any mouthpiece, and can fit in any style. The 3B is one of the most versatile trombones ever made, especially with an F attachment, and though I have tried dozens of amazing small bore trombones over the years, I have yet to find a reason to replace this 3B. I recently had the bell section delacquered, and I am in love with the dark, uneven finish that came out.

1970 King 3BF

I got this instrument years after the 3B above, but it plays EXACTLY the same. The valve really makes no noticeable difference to the sound or feel. It’s been really nice to have the option of valve or no valve depending on the gig, and I have used this 3BF a ton. However, I don’t REALLY need two trombones that play the same, so it is currently in the shop along with two King 607s below having mad science done to it.

1967 King 607

The 607 is marketed as an “intermediate” trombone, but in reality it is a King 3BF with a straight bell brace and a yellow brass .525” slide. The result is an instrument that plays the same as my 3B and 3BF, just a little bigger. It has a monstrous low register in exchange for a high register that’s only slightly more difficult than on the 3B/3BF. It also happens to record the best out of any of my trombones - on a mic, the 607 punches WAY above its weight. I’ve used this trombone a lot, and it is about to get even better (see above).

1976 King 605F

The 605F is not the same beast as all the 3Bs or 3B-based trombones above. It is truly a student-level instrument, and is just a garden variety Cleveland 605 with an F attachment. This means it has a .491” bore and a student-grade slide, bell, and leadpipe. It is nowhere near the quality of the Kings above, but it is fairly rare and interesting for being such a small bore with an F valve. However, I really only bought this (on eBay for cheap, naturally) to use as a parts horn for an alto trombone project, which is ongoing.

1978 King 1306 Tempo

The King 1306 is an all-nickel or nickel plated intermediate model with a .500” bore and 8” bell. It retains the curved bell brace of the professional models, but has the narrow chassis of the student model trombones like the 605 and 606. It has a reputation for being one of the loudest trombones ever made, and I think it lives up to that! But it’s a nice player at normal volumes as well, and plays easily. I had the tight-feeling stock leadpipe pulled and replaced it with a press-fit Kanstul HO .500” press-fit leadpipe, which opened up the horn considerably. This horn is a weapon!

1979 Olds Recording R-20 in C

This is an Olds Recording R-20 (.495/.510” dual bore, .515” valve section, 8.5” bell) that was cut from B-flat to C, with the valve tubing cut from F to A. Tenor trombones in C are very rare, with most being set up to stand in B-flat with an ascending C valve (so not really meant to play in C), like the Yamaha YSL-350C. This one is meant to be fully played in C, with the minor-third attachment providing the same functionality as it does on a Bb tenor (in G) or Eb alto (in C). The A valve also makes the lowest chromatic note E2, the same as a normal valveless B-flat tenor trombone. This instrument sounds somewhere in between a small (B-flat) tenor and an alto, and is a very fun horn to play. The biggest downside is that the left hand ergonomics are horrendous, just like all Olds trombones with valves.

2023 Y-Fort YSL-763L

This is my main large bore tenor, which I use for most classical tenor gigs. It is a fabulous horn that I bought straight from the Y-Fort booth at NAMM. It eliminates a lot of the headaches I usually have with large bore trombones, and just works everywhere, no matter how long it’s been since you’ve played it. I replaced an excellent Elkhart 88H with this, and I couldn’t be happier. It also came with an excellent Marcus Bonna-style screw bell case, for no extra charge!

Early (1990s) Willson 411TA with G valve

This large bore tenor trombone is extensively different than the standard 411TA you can order from Willson. The most obvious difference is that the valve attachment is in G rather than the usual F, but additionally the valve is an ULTRA rotor (instead of a Rotax), the attachment tubing matches the slide tubing at .547”, and the slide has a Saturn water key. This is a great-playing instrument with a dense, colorful sound, and the G valve allows for much more fluid slide movements in the middle and low registers. It’s also extremely cool, with a unique push-button slide lock and titanium nitride-coated inner slides.

Early (1990s) Willson 311TA with G valve

This is the 411TA’s medium bore stablemate, with a .525” slide and 8.26” bell instead of the 411TA’s .547” slide and 8.66” bell. Like the 411TA above, this 311TA also has a G valve with matched bore (.525”) tubing, this time furnished with a Caidex valve instead of an ULTRA. It plays and sounds very similar to the 411TA, but it has that .525” lightness, agility, and all-around ease that you just don’t get on a .547” horn. The sound is colorful and malleable, the Caidex valve is superb, and the instrument is addicting to play.

Bach 42G with G valve

This is another G valve conversion like the Willsons above. It also has an ULTRA rotor, and the valve tubing is the more typical .562”. The handslide is a lightweight nickel dual bore .547-562” slide, ensuring the lower slide bore matches that of the valve tubing. This is a nice playing example of a modern Bach 42, and the G tuning, ULTRA valve, and dual bore slide all work beautifully together. This horn now belongs to a friend of mine.

Conn 88HT with G valve

This is yet another G valve conversion, with an ULTRA valve and .547-.562” handslide (in this case a Conn SL5462). It is a rock-solid example of a modern 88H with the additional utility of the G valve. This one also now belongs to a friend of mine.

Yamaha YSL-3540R and YSL-456G

These are two nearly-identical dual bore Yamaha tenor trombones, which I bought directly from Japan. The top one is a YSL-3540R, and the bottom is a YSL-456G. As far as I can tell, the only differences are the bell material (red brass on the 3540R, rose brass (“gold brass” in Yamaha-speak) on the 456G) and nickel trim on the F-attachment loop on the 456G. Otherwise, their appearance and specs are identical: 8” bell, .500-.525” dual bore, small shank, all-yellow brass outer handslide, .530” F attachment. As a result, they play pretty much identically; to me the 456G plays a smidge better, but it’s a small difference. They are excellent players; beefy dark sound for a trombone this size that sounds like a mini .547 rather than a typical small bore, easy across all registers, and no quirks to speak of. Also a bit boring, to be fair. These have since been parted out; the valve sections were harvested for use in my double valve 3B project, and the rest was sold as parts.

1962 Conn 88H

This Elkhart 88H was my large bore tenor for quite a few years, until I replaced it with the Y-Fort 763L. It had that magic Elkhart sound, and when you were in tune with the horn it was a wonderful player. But if you didn’t play the horn every day, it would really punish you. As someone who rarely gets called to play classical tenor, that meant the horn and I rarely agreed and it was often a struggle.

Yamaha YSL-682G

I bought this mainly out of curiosity, and I learned that it was a solid, dependable large bore with a pleasant sound and no surprises. Nothing super inspiring, but a great workhorse large tenor. If I had still been on my 88H when I bought the 682G, I would have replaced the 88H with the 682G without hesitation. But since I had the Y-Fort, I had no use for the 682G and it was gone quickly.

Unmarked German quartposaune

This German trombone was really in project condition when I got it, but I still used it on a few gigs and a multitrack in spite of that. It had a beautiful dark German sound unlike any other trombone I owned, and sounded full and rich in all registers - a true tenor-bass trombone. However, I was totally unwilling to spend the money necessary to make it comfortable to use, so off it went.

Selmer Largo

The Selmer (Paris) Largo is a fairly rare and very French large bore tenor. It was my first large bore, and in hindsight I probably should have bought the world-beater Holton 156 that I also tried that day instead. But at the time, I was completely enchanted by the captivating, velvety sound of the Largo. It really did have a special sound, and would be fabulous as a classical trombone soloist’s instrument. But I am not a classical trombone soloist, and the totally alien intonation and bright sound made playing in ensembles a losing battle. I later acquired another Largo bell section with 9” bell and F-attachment, which helped somewhat, but was still not enough to offset the horn’s many quirks. So I sold the Largos, bought an Elkhart 88H (see above), and didn’t look back.

1982 King 3B+F

The 3B+F is the real deal .525” 3BF - no sheep’s clothing like the 607. It has a proper nickel slide like the 3B, a gold brass bell, and the signature curved bell brace. It plays very well as you would expect, though it does sound and respond a little differently than my other 3Bs/607s thanks to the rose brass bell. Ultimately, I concluded that I preferred the sound of my yellow bell 3Bs and 607s, so I sold this one on.

1965 Conn 77H Connquest

The 77H is an uncommon Conn model that was sold as an intermediate model, but is essentially a 6H with a half-inch smaller bell. My 77H (which came with a King Cleveland counterweight for some reason) was yet another cheap eBay acquisition to see if the 77H was a hidden gem. I concluded that while it was a nice player, it wasn’t for me as the 6H’s bigger bell (and the bigger sound it creates) is part of the reason that I love the 6H. So I sold it on.

1966 Holton 66 Galaxy

This is the first instrument I ever bought on eBay. I got it for $90 in high school, to use in the school jazz band. It was my only small bore trombone until I bought my King 3B after I graduated undergrad in 2015, and served me well. It had a very bright, cutting sound to match its all-nickel plate construction and .485-.500” dual bore, and was great for New Orleans/second line. But ultimately it was too small for me, and I was very happy to trade up to the 3B.

1940 Holton 63

This is a rare Holton small bore model (.480-.495” dual bore, 7.5” bell) that I owned briefly during grad school. It was a nice player with a very pretty sound, but ultimately I concluded once again that it was too small for me, and sold it on.

Bass Trombones

1963 Conn 72H

This is my main bass trombone, and has been since I bought it in 2017. It has an independent valve set from what looks to be a Yamaha YBL-830, and I bought it in that configuration. I bought it after having used a stock single-valve Conn 72H bass trombone as my only bass trombone for awhile, so it was the perfect upgrade. This bass trombone is a wonderful instrument that can go toe-to-toe with anything out there. It is perfect for big band playing, but I have also used it in big orchestras, opera pits, recording sessions, and chamber music and it fits beautifully in every situation.

Early (1990s) Willson 551TA

Willson bass trombones are rare and interesting, and this is possibly the most unique Willson bass trombone out there! This is a 551TA that heavily departs from the stock configuration. The valves are pitched in G and E instead of F and Gb, and the valve tubing is wrapped beautifully, with the E tubing flanking the G wrap on both sides. This tubing is also .562”, matching the slide bore. Everything else is standard: .562” nickel slide with unique titanium nitride inners, push-button slide lock, and a huge, dense sound. This instrument is an excellent complement to my 72H, as two instruments’ sounds and valve tunings are quite different and best suited to different musical situations.

1932 Conn 70H

Before the 70H became the single-valve workhorse used by George Roberts and others, it spent a few years looking like this. It has a manual change rotor from F to E and a dual bore .547-.562” slide, but it sounds and plays like every 70-series bass trombone that came after it. But it also has something more. Something extra special to the sound and feel. This is a very special instrument, and I found it in a Guitar Center!

C. F. Zetsche & Söhne G bass trombone

This is one of the most modern long bass trombones I have seen. I have owned two others, and each had a lion’s share of issues. Dead partials, non-existent high register, stuffy, horrendous slide, physically heavy, etc. This instrument has NONE of those issues. It is genuinely as easy to play as my B-flat bass trombones, and has a big open bass trombone (NOT contrabass trombone) sound. The valve plays nicely and is fairly comfortable to activate. Interestingly, the attachment wrap is a tritone lower (D-flat) rather than the usual perfect 4th (D), and it also has a very long pull that can lower it all the way to an in-tune perfect 5th (C). The slide has a full seven positions and a gimballed handle, and the slide bore is a modern .550”. This is the modern long bass trombone that I dreamed of!

1939 Boosey & Hawkes Artist’s Perfected

This is a traditional small-bore (.484”) British bass trombone in G. It has a full-length slide with handle, no leadpipe, and all the bark the G bass trombone is famous for. Unfortunately, the handslide is not plated, very heavy, and ultimately unusable. The instrument also has a common small British G bass trombone issue of a dead 3rd partial, and even with 2 counterweights is still very front-heavy. I eventually returned it to its original owner when I got my German G bass trombone.

1937 Julius Rudolph F bass trombone

This is a very heavy German bass trombone in F. It has a massive bell throat and a massive difference in upper and lower slide bores: .540-.610”! Despite being designed as a bass trombone, it has an enormous sound that sounds as broad and powerful as a modern contrabass trombone to my ears. I’m so glad I got the chance to own this, but I was searching for a true bass trombone sound rather than a near-contra sound, so I sold it to a friend who has since had a ton of work done to it, including adding two valves.

Benge 290

The Benge 290 was the successor to the King 8B, which was the successor to the 7B and 6B Duo Gravis bass trombones. It was the swansong of the King style of bass trombone design, with a narrow slide and round yellow slide crook like the tenors. The 290 balances this slide with a heavy 10” bell with a large, Bach 50-like throat, resulting in a bass trombone that has a pretty unique sound and blow. The sound is a big and dark, yet has some cool vintage color…but not a color you can place as being similar to anything else, like a Conn or a Bach. It is kind of its own thing. This particular 290 was in excellent shape, and while it was fun to play, I didn’t gel with it enough to keep, so off it went.

196x Conn 72H

This is the stock (apart from the valve slide stopper, which I never used) single-valve 72H I was playing on when I found the double-valve 72H. This came with a modern Conn SL6262 slide when I bought it, which really wasn’t a match for the bell as it was too short, but I made it work. Once I got the double 72H, I sold the SL6262 and just swapped single and double bell sections with the proper 72H slide. I kept that up for awhile, but eventually sold the single valve bell section as it didn’t provide a big enough difference in sound compared to the double valve section to be worth keeping around.

1972 Olds S24G

The Olds S24G was the first production independent bass trombone in history, and this one came to me with these modified open wraps. It was a great player, with a dense, colorful sound that I really loved. Unfortunately, the small rotors made the trigger register stuffy, and the trigger paddles were the most uncomfortable setup I have ever tried on a bass trombone - my left hand would be in pain within 30 seconds. If I had had a boatload of spare cash at the time, I might have had new valves and linkages put on it and had a world-beater. But I also still liked my indy 72H more, so I sold it.

2006 Getzen 1052FD

This was my first bass trombone, and it took me all the way through my undergrad. It was a great starter bass that was made even better when I eventually got a BrassArk leadpipe for it.

1964 King 1480 Symphony

While some people think of the King 1480 as a large tenor, it is really a small bass trombone, and Bart Varselona played bass trombone in the Kenton orchestra on one. This was the second 1480 I owned, and I bought it to use in a small opera orchestra that stopped using trombone shortly after I bought it. So the horn sat and sat unused, and I eventually sold it. Oh well!

1960 King 1480 Symphony

This was my first King 1480, which I owned many years before I got the later one above. Note the different F wrap compared to the 1964 model.

Conn 71H (not pictured) - I very briefly owned an Elkhart Conn 71H. I saw it on eBay for a good price and Buy It Now, so I snagged it. However, once it arrived I only had to play a few notes on it to know that it was a dog. Fortunately, the seller accepted returns so I packed it back up and took it back to the post office that same day.

Valve Trombones

1985 King 1130 flugabone

This is the classic flugabone, and the model that coined the term. I got this on eBay for a whopping $67 many years ago - no small feat considering the prices they go for nowadays. I have owned several other flugabones (as well as a valve trombone and a trombonium), but the King is the one I kept. It has a shouty sound and is much louder than the Olds design, both of which are advantages for the situations I use it in (mainly cumbia). I’d love to get another one and cut it to C. I recently had this instrument delacquered, and as you can see the results are spectacular.

Olds O-21 flugabones

The Olds O-21 is regarded as one of the best flugabones, along with the King 1130. It seems to be a more refined design than the King; the sound is closer to a slide trombone and is smoother than the King, and the instrument plays very well with no stuffiness or bad quirks to speak of. The only disadvantage I can think of that it does not have the 3rd valve slide kicker like the King does, and it does not project as much as the King does. But for somebody who does not need to compete with amplified instruments and very loud trumpets and trombones, the Olds is the better instrument. It sounds the closest to a slide trombone out of the flugabones I have played, and its generous .515” bore really helps to keep it feeling nice and open. These are wonderful instruments, and I have had 3 different ones in my possession at various times. The two pictured are a 1977 (lacquer) and a 1978 (silver), both of which came to me in rough shape before being rehabilitated by my tech.

Blessing Artist M-200 flugabones

The Blessing M-200 is the same basic design as the Olds O-21s above, as is the Reynolds TV-29. The Olds and Blessing play similarly, though the Olds is more suited to classical flugabone playing (if such a thing existed) while the Blessing is more suited to smoky jazz flugabone playing. Like the Olds, the Blessing cannot match the projection of the King 1130, but is a great player nonetheless. I’ve owned two of these, and I enjoyed them quite a bit, but the King is a better match for the situations I use flugabone in.

1940 King 1140 trombonium

This is the original trombonium, and the same one that J.J. Johnson and Kai Winding played on occasion. I bought it out of curiosity, but I was not prepared for just how good this instrument is. The 1140 blew every flugabone I’ve owned out of the water in both sound and playability. It was an excellent instrument and great fun to play. However, I could not get past the bad ergonomics, hugely inconvenient form factor, and awful factory case (with no available aftermarket replacements), so I made the tough call to sell it.

Jupiter JVT-528

A bog standard Bb valve trombone. It has great valves and a nice sound, and is a fun player. There is absolutely nothing to complain about with this instrument, but I choose to stick with my flugabone for its more compact and ergonomic form factor, so this valve trombone now belongs to a friend of mine.

Alto & Baritone Horns

Boosey & Co. Solbron Class A alto horn

This is my compensating (!) Boosey alto horn. It has a beautiful engraving on the bell and has a lovely sound. Unfortunately the valve compression isn’t the greatest, but with thick valve oil it still plays well.

Jinbao JBBR-1240 baritone horn

This British-style baritone horn is one that I had tried many times at conventions before buying one. I have tried all the big name baritones - Besson Prestige, Besson Sovereign, Yamaha Neo, etc…and this little Jinbao (I think a Sovereign clone?) is as good or better than all of them. So when this one showed up on eBay for cheap, I was quick to snap it up. I have used it quite a bit since then, and it still impresses me as much as it first did.

Blessing Artist M-300 marching baritone

This is the same model of marching baritone that I used in high school marching band. My high school had a couple of these old Blessings, and a few newer Kings. The Blessings were traditionally given to the freshmen, while the upperclassmen got the shiny Kings. But I quickly found that not only did the Blessings play better than the Kings, they were genuinely good instruments in their own right and not just by marching band standards. When I eventually became section leader, I assigned myself a Blessing while everyone else got the Kings. I liked it enough that I tried to buy mine from my band director when I graduated, but she wasn’t allowed to sell it to me. 13 years later, I finally have my own Blessing M-300, and this one is sticking with me.

Tubas & Euphoniums

Kanstul 902-4C tuba

This is a 3/4 C tuba that, while looking very worn, plays wonderfully. It is very easy to play in all registers, has good intonation and easy slide pulling, and sounds bigger than its small size would suggest. I also got it for an absolute steal of a price, so it really checks all of the boxes for a tuba doubler like me. It would be nice if it had a 5th valve, but it is already heavy as is so I don’t mind that it doesn’t.

Schiller Elite IV euphonium

This is yet another weirdly-great Chinese clone - in this case a clone of the Yamaha YEP-642. I actually replaced a Sterling Virtuoso with this, because it was more consistent between registers and because I could no longer justify owning a fancy $3k+ euphonium when it never leaves the house. Such is the plight of most euphonium players after college. But this Jinbao model is hardly a bad instrument - it is a good euphonium by any standard. Would I like to have a nicer euphonium? Of course…but how could I justify it?

V.F. Cerveny Eb althorn

This althorn is essentially an alto tuba, and sounds like it. It makes a very dark, euphonium-like sound, but in the alto register. I eventually plan to either add valves or put on a totally new valveset to make it better, and maybe finally realize my dreams of having a fully-chromatic alto euphonium.

2007 Sterling Virtuoso

This is a very early Sterling Virtuoso euphonium, and is one of the coolest-looking euphoniums I’ve ever seen. It played great, too - in the upper register it had the colorful, lyrical sound of a Besson, while in the middle and low register it had the broad, dark sound of Willson. It was an interesting combination, and a great overall result. But despite everything I just didn’t gel with this instrument, so I eventually replaced it.

2008 Kanstul 975

This is a very early Kanstul 975 - likely a prototype. It was my first euphonium, and I had it for 11 years. It served me very well especially in my undergrad, and there was a lot to like about it. It remains the most comfortable euphonium to hold that I’ve ever played, which is a huge deal when most euphonium designs apparently don’t consider left-hand comfort at all. It had a nice sound somewhere in between the Besson and Willson extremes, and it had a monstrous low register. But it also had the usual intonation quirks present on every euphonium, and a few additional quirks not present on others. The worst one was that F in the staff was very sharp played open, so you had to play it with the 4th valve, which changed the sound a lot. It also had very heavy pistons, which were hard on the fingers when played for long periods. It was those two quirks that were the primary motivation for me to find a replacement after 11 years, and the 975 was eventually sold to a local high school band program.

Pelisson bass saxhorn in C

This early-20th century French bass saxhorn had a lean, compact euphonium sound. Being in C meant it was a pretty different experience from playing euphonium, which I liked. However, the valves were totally worn out and it really needed a full restoration to be worth keeping, so I sold it on.

Boosey & Hawkes Imperial Eb tuba

This is a classic 15” bell British compensating Eb tuba. It had a sweet sound and was essentially a big euphonium, which was exactly what I wanted. Unfortunately, it didn’t stick around too long for three important reasons. First, the pistons were totally worn out and the instrument really needed a total restoration to be usable. Second, I pretty much never used it. And finally, I lived in an absolutely TINY bedroom at the time, and a massive tuba that I never used was the last thing I needed. It was a very easy decision to sell it.

Brass Instruments I Have Yet to Own, but would like to

Natural horn

Parforce horn

Alexander 103 double horn (or similar…203ST, Yamaha 869GD, etc.)

Kanstul 285 Bb marching horn

Dynasty II 2-valve G French horn bugle

Cheap rotary piccolo trumpet

High F trumpet

Bb and/or C rotary trumpets

Kanstul 3-valve G soprano bugle

Contrabass trumpet (probably made from parts)

Eb cornet

C cornet

Pro-model British Bb cornet

Rotary circular alto horn

A nice Bb oval tenorhorn

Eb (or F) soprano flugelhorn

4-valve flugelhorn

Corno da caccia

Kanstul KMM-280 F marching mellophone (early pattern)

Harry B. Jay Columbiaphone

Large bore Bb soprano trombone

G soprano trombone

F alto trombone

Conn 6H (Elkhart) tenor trombone

F contrabass trombone

F cimbasso

Superbone

Alto, tenor, and bass sackbuts

F tuba

Valved ophicleide

Alto Flugelhorn

There are alto trumpets, alto cornets, alto bugles, and of course alto horns, along with many other alto-voice brass instruments that have more interesting names. But what about an alto flugelhorn? This would be an instrument a 4th or 5th below the standard flugelhorn, still with a flugelhorn bore profile. This instrument does exist, but it’s not very common. It’s even rarer than alto trumpet or alto cornet, but it seems to bring more to the table than either of those do.

Here’s an alto flugelhorn - an “Elkhart”-stenciled Couesnon alto flugelhorn in F or E-flat:

This instrument has a gorgeous low flugelhorn sound that matches my Couesnon flugelhorn very well. In my opinion the sound is so purely flugelhorn that if someone heard an audio sample without knowing what instrument was playing, I’m guessing most brass players would immediately guess a 4-valve flugelhorn or maybe some other kind of flugelhorn. It does have a subtle hint of euphonium to the sound as well.

This alto flugelhorn plays just as well as my fabulous pre-WWI Couesnon flugelhorn, and is one of the better-designed/easier-to-play bell-front alto brass instruments that I’ve owned and played. It’s wonderful, and the sound is creamy smooth.

These Couesnon alto flugels used to grow on trees on eBay, but in the past decade or so they sort of disappeared. I was surprised when this one showed up, and this time I didn’t let it pass me by. I enjoyed owning it and used it on my 2023 Christmas multitrack, but I no longer own it. First, I realized that my Kanstul 275 marching alto was actually better at being an alto flugelhorn than this actual alto flugelhorn…and then I realized that I didn’t even need that as my Holton M602 mellophonium is equally as good at being an alto flugelhorn as the Kanstul 275, while also having much more character. So off both went.

I have owned an alto trumpet, alto cornet, alto flugelhorn, and 2 alto bugles, but sadly none at the same time (so no back-to-back demos). But this alto flugelhorn sounded VERY different than the alto cornet did. It had that velvety flugelhorn darkness that the alto cornet just didn’t have, much more like the Dynasty III alto bugle in G (which is essentially an extra-large G flugelhorn).

Couesnon alto flugelhorn (left), Couesnon flugelhorn (right)

Here’s a quick back-to-back comparison I did of my Couesnon flugelhorn and the Elkhart (Couesnon) alto flugelhorn. Hopefully, despite the phone microphone, you can hear the subtleties in each instrument’s sound.

Lastly, here are some photos of other types of alto flugelhorn out there. Most are in E-flat, which makes sense as the even rarer soprano flugelhorn is also in E-flat.

B-flat Tenor Brass Audio Comparisons

Bass trumpets. Flugabones. Trombones in various bore sizes. Baritones in various shapes and sizes. Euphoniums. There are so many different kinds of 9-foot B-flat brass instruments that broadly function in the tenor register, so how do you justify them all?

Easy: they all sound different! Admittedly sometimes the differences are small, but the differences ARE there. Each was designed for a different purpose, but how do they compare when you put them head to head? Time to find out!

What follows is a cornucopia of audio files from various 9-foot instruments that I owned or had access to long enough to sit down and record for a while. This is by no means complete yet; I have a bunch more instruments and instrument/mouthpiece combinations to record, and I will continue adding to this as I gain access to different instruments. It is a forever work in progress, but hopefully before long it will be a comprehensive archive of most of the B-flat low brass out there. I may add tenor brass in other keys as well, but I’ll have to rework the excerpts to accommodate their ranges.

For now, let’s take a brief look at the instruments I’ll be demoing.

1970 King 3B Concert tenor trombone (.508” bore)

This is my main gigging commercial tenor trombone. It is extremely versatile, equally at home knocking down buildings on a funk or salsa gig or playing in a brass quintet. I use two mouthpieces with this instrument - a Warburton 8S/4* (very shallow lead mouthpiece) and a Hammond 11M (normal-depth V-cup general purpose mouthpiece).

1979 Conn 5H tenor trombone (.500” bore)

This is an Abilene Conn 5H, which is a lightened 6H. It tends to have a bright sound with lots of core, great for pop work. I only trialed this instrument and ended up not buying it, but I had it in my possession long enough to use it on these demos as well as a few other things. It didn’t like my Hammond 11M, so I used it only with my shallow Warburton 8S/4* (which it liked very much).

1985 King 1130 flugabone (.500” bore)

The source of the word “flugabone”, and a very good player. I’ve gigged on this a ton and its shouty sound is a great asset to have. Gotta be careful with mouthpiece choice though!

1973 Olds O-21 flugabone (.515” bore)

Another flugabone (or “marching trombone” in Olds-speak) that feels more refined and restrained than the King 1130. The better choice for classical flugabone playing (???). This specific O-21 is another instrument that I trialed but ending up not buying, though I ended up owning multiple O-21s later.

Josef Lidl rotary Bb bass trumpet (~.440” bore)

An old-school bass trumpet with a very small bore, that makes up for its difficulty with its piercing trumpet sound.

Blessing Artist M-300 marching baritone (.562” bore)

An older model of marching baritone that plays very well with a nice, colorful sound. I used this model baritone in high school marching band! This model also has a Bauerfiend valve set for some reason???

The Excerpts

I’ve prepared five contrasting excerpts to showcase the differences in all the instruments that will be playing them. (And by “prepared”, I mean “improvised on the spot when recording the first instrument”.) They are all very short, but give some good information. All instruments were recorded close-mic’d into my Cascade Fat Head ribbon microphone. I generally left intonation foibles in rather than re-taking until it was perfect, as tricky intonation is an important part of playing each instrument.

First up is a short marcato excerpt with 3 parts. I divided up the takes into 1 part solo, 3 parts (1 on a part), and 3 parts tripled (3 on a part).

Solo first:

3 parts (1 on a part, no doublings):

3 parts tripled (3 on a part) and panned to simulate a large section:

The next excerpt is a very short, softer triadic statement that starts high and ends low. As with the last excerpt, this one has 3 parts and was recorded the same 3 ways.

Solo first:

3 parts (1 on a part, no doublings):

3 parts tripled (3 on a part) and panned to simulate a large section:

The next excerpt is quick, high, and loud. 3 parts, nothing else. Very simple.

This one is a brief jazz excerpt in a typical 4-part big band trombone section style.

The last excerpt is a short 4-part chorale on the softer side. Starting with just the 4 parts, we’ll go through some fun variations later.

4 parts, no doubling:

The same stems as above, but this time drenched in some nice reverb:

This time each of the 4 parts is doubled, making for 8 total players.

Now we take the doubled parts and bring the reverb back.

Just for fun, after I finished recording the first 6 instruments, I unmuted all tracks on the chorale and exported that result too. This makes 48 players on 4 parts - 12 on a part, 2 per instrument. Just in case you ever wanted to know what a massed choir of bass trumpets, trombones, flugabones, and marching baritones sounded like.

Finally, I thought the massed chorale sounded so good that I decided to try pitch shifting the whole thing to see how it would sound in different ranges. I started by pitching down, but I was not prepared for the heavenly trumpet sound I got when I pitched up!

That’s all for now. As mentioned at the top of the post, there are still more instruments to record. At the very least, I have 4 trombones, possibly a bass trombone or 3, British baritone horn, and euphonium to add to the pile. In time!

In the mean time, if you’re interested in more comparisons, I uploaded some quick phone mic comparisons of some of these instruments on YouTube a few days ago.

Brass Instruments That Don't Exist (But Should)

It goes without saying (especially on this particular website) that there are a lot of brass instruments out there. Some probably shouldn’t exist, and others are probably not distinct enough to really deserve their own name. But they exist nonetheless, and going down the rabbit hole to discover and make sense of all of them is an endeavor that takes years.

But even though the concept of a mouthpiece attached to a metal cone has been tried hundreds or even thousands of ways, I believe we have not explored all that is possible in the brasswind medium. More to the point, I believe there are some brass instruments that should exist…but don’t. That’s what I’m going to discuss here, and hopefully inspire intrepid makers to make them a reality. (I can dream, ok?) Naturally, these are just my personal opinions, and if you have a different idea of a non-existent brass instrument that you wish was less non-existent, I’d love to hear about it.

Yamaha YEH-901ST alto euphonium in E-flat (picture from Hidekazu Okayama’s website)

Alto Euphonium

This might be the instrument I wish existed the most - a true F or E-flat alto tuba in the British euphonium style, with 3+1 compensating valves, a much larger bore and bell throat than an alto horn, and a small trombone mouthpiece shank. Technically, an alto euphonium does exist: the Yamaha YEH-901ST, which was made in a very limited (14 or 15) run in 1984-85 for Yamaha artists. It only had 3 valves, none of them have ever been for sale, and Yamaha no longer has the tooling to make any more. So although it technically does exist, practically speaking it might as well not. But this is the idea.

I plan to get an alto euphonium custom made for me from parts, as I really believe in its potential. Hopefully that project might inspire makers to give the concept a try. If my alto euphonium project is successful, I may then think about trying a soprano euphonium as well.

Besson BE765C-2 euphonium in C (left), Besson BE765-2 euphonium in B-flat (right). Picture from Hidekazu Okayama’s website.

(Compensating) Euphonium in C

A similar (but less radical) instrument I’d like to see more of is a professional compensating euphonium in C. This did exist as the Besson BE765C, a special order instrument available until the company moved to Germany in 2006. That tooling is also likely long gone, and the picture below is the only evidence I have ever seen of the model. I can’t imagine more than a handful were ever made.

C euphoniums do exist and are used in some parts of the world, but apart from the Besson above there are none that I know of that are British-style professional instruments. C tubas are a standard for orchestral tubists…I see no reason why a British-style compensating euphonium in C couldn’t also have merit, especially as a doubling instrument for tubists used to C fingerings.

6/4 American-Style Tenor Tuba

There have been some extra-large compensating euphoniums in the past, but what I’m proposing goes a step further. Massive 6/4 York-style C tubas are very much in vogue…why not try that same blueprint an octave up? Give it 4 front-action pistons with a 5th rotor and orchestral tuba players will flock to it as a doubling instrument even more than the C compensating euphonium mentioned above.

Bass Euphonium

I know what you’re thinking: “Isn’t a bass euphonium just an F tuba?” And I don’t blame you for thinking that, especially when small bell British F and Eb tubas that look and sound like big euphoniums exist. But my thought for an instrument called “bass euphonium” would be to take the dimensions of a modern compensating euphonium (.590” starting bore size) and use them to build an instrument in low G. The goal is an instrument somewhere in between a euphonium and bass tuba in sound. I will admit, this one isn’t that important to me, but I think it would be an interesting experiment. I have seen a few very small bass tubas for sale that have seemed like really good candidates to cut down into a bass euphonium. I’ve even seen a piston F tuba with a 12-inch bell!

A custom Holton Bb soprano mellophonium, made from parts

Soprano Mellophone/Mellophonium

A soprano mellophone in high B-flat is something I’ve wanted for a long time. A couple have been cobbled together from parts using trombone bells (see the above picture), but that’s not really the real deal. I’m talking new mandrels and tapers that match a modern mellophone, just a scaled down for an instrument a 4th higher. I would suggest still using a trumpet shank and the same bore size as an F mellophone, as you still want it to feel like a mellophone. Truthfully, I would love a soprano mellophonium with a .500” bore, the same as the Conn 16E mellophonium. But as no maker makes a bell-front mellophone that large anymore, you’d have to do that first and then make the high Bb version. Which…I would also welcome with open arms. I love my 16E, but that design leaves a ton of room for improvement by a modern maker.

Lower Mellophones

If the mellophone formula can be expanded upwards, why not downwards as well? I used to own a Conn 8E ballad horn from 1930, which is essentially a tenor mellophone in C or B-flat. But (to my knowledge) a modern bell-front tenor mellophone is not something that anyone has ever attempted. I even think a bass mellophone in F (an octave below the standard mellophone) would have a lot of potential.

I have been fascinated by the idea of a complete mellophone or mellophonium family for a long time, and even drew freehand sketches of what I would imagine some of the non-existent members could look like.