Soprano Trombone

Do you want to buy a soprano trombone? Do you want to know why the soprano trombone exists? Do you want to explore the weird world of comically small trombones? If you answered “yes” to any of those questions, this article is for you.

The soprano trombone isn’t as endangered as most of the other instruments I write about on this site, and there is a good amount of information about it online. But I’ll start with a brief summary of what it is in case you’ve discovered it first through this article.

Thein soprano trombone

The soprano trombone is a trombone pitched one octave above the standard tenor trombone; in other words, it is pitched the same as a standard B-flat trumpet. It usually has a trumpet shank and can be played with a variety of mouthpieces. Nowadays you can buy extremely affordable Chinese soprano trombones from quite a few vendors, but almost nothing has ever been written for the instrument and professional-quality soprano trombones are very rare. Soprano trombones are sometimes referred to and marketed as slide trumpets; it’s easy to understand why, as the cheap ones are usually made with trumpet parts and they sound like trumpets when played with a trumpet mouthpiece. But the name “slide trumpet” was already taken by an interesting Renaissance trumpet variant centuries before anybody ever applied it to the soprano trombone, so it is better to avoid. Interestingly, in the early 20th century manufacturers sold both “slide trumpets” and “slide cornets”, the only difference being the mouthpiece shank.

Despite being a logical member of a very well-established instrument family, the soprano trombone has almost never been explicitly written for. There are good reasons for this, and good articles and academic publications have written at length about the subject (especially regarding early music). The only place where the soprano trombone gained a permanent foothold was in Moravian trombone choirs, whose core instrumentation was a large mass of trombones from soprano to B-flat contrabass. Even the German Posaunenchor ditches the soprano trombones for Kühlohorns (a variety of rotary flugelhorn) on the top parts, and most trombone choirs do not use anything above alto trombone at all. More recently, the soprano trombone has garnered some attention from its use in jazz by Wycliffe Gordon, but apart from this and the efforts of contemporary classical soloist Torbjörn Hultmark and avant-garde jazz soloist Steven Bernstein, the instrument remains essentially unused in any notable capacity.

In my opinion, there is a simple reason for this: nobody knows what mouthpiece to use for it.

Cheap Chinese soprano trombones always come with a generic 7C trumpet mouthpiece. This makes it sound like an out of tune trumpet and is not desirable. Wycliffe Gordon uses his own custom hybrid mouthpiece with a trombone rim and cup on a trumpet shank, but while you can order these from Chasons, they are very expensive. Someone interested in dipping their toes in the soprano trombone is not likely to want to spend $300 on a mouthpiece for it, especially if its only documented use is by Wycliffe Gordon, who is hardly a normal player like us mere mortals! As a result, the few who do buy soprano trombones typically don’t venture very far off the trumpet mouthpiece path.

I have long held my own theories about what the ideal soprano trombone mouthpiece would be, and I have been able to test some of these theories to favorable results. I used to own an extremely cool soprano trombone, which I have to share here:

This is a handmade German soprano trombone, with a rotor that has slides to put it in A, Ab, G, or F. The rotor is activated by an old-school leather strap rather than a modern paddle, and the bell has a kranz. There is no maker’s mark to be found, and it is likely an exam instrument made by a journeyman apprentice. It is impossibly cool, and I am so thrilled to have owned and played it. It’s gone now, in the hands of someone who will use it more than I did.

Now, on to the mouthpieces. I tried a fleet of mouthpieces on that soprano, to varying degrees of success. These are my findings:

Trumpet mouthpieces: it sounds like a trumpet. Very fun to play this way, and there are certainly musical uses for a trumpet that can do true glissandos and other slidey things, but the goal here is to get a proper trombone sound that fits perfectly on top of alto and tenor trombones. For that, trumpet mouthpieces are not the way.

Bach 9AT alto trumpet mouthpiece: I always thought this would be the solution, but thanks to its oversized shank (it is not just a normal trumpet shank!), it does not work very well in the soprano. It does get an amazing beefy trombone sound, but it is very difficult to play high on, so much so that it offers no real improvement in range over an alto trombone.

Schilke 24 trumpet mouthpiece: This is a massive trumpet mouthpiece, somewhere in between any normal-sized trumpet mouthpiece and the Bach 9AT above (inner diameter 18.29mm). I thought it might do well, but it ended up being nearly as hard to play as the 9AT but with a thinner sound. Not the move.

Denis Wick 2 alto horn mouthpiece: even harder to play on than the 9AT, which is not surprising as the DW 2 is the biggest alto horn mouthpiece Denis Wick makes. It is BEEFY.

Kelly 3W alto horn mouthpiece: the Kelly is a deeper British-style alto horn mouthpiece like the Wick 2, but it is significantly lighter (being plastic) and is not as large or deep. The result works well in the soprano. The tone is nice and dark, with a trombone-like broadness. Range is good too, with a comfortable range up to Bb5. It still feels too deep both from a sound and effort perspective, but it doesn’t feel too far off the mark for a broad classical soprano trombone sound. The alto horn-sized rim also feels right for instrument, and my bass trombonist face certainly appreciates the additional room.

Marching mellophone mouthpieces: I tried 3 of my marching mellophone mouthpieces (Hammond 5MP, Benge Mello 6V, CKB Mello 6) and they all worked about as well. These get a bright sound that is definitely not the right move for classical playing, but for playing jazz on top of small tenor trombones the sound feels just about perfect. There is lots of snap and sizzle to the sound, but it is still much fatter and noticeably more trombone-like than with a trumpet mouthpiece. Articulations also sound like a trombone rather than a trumpet, and the range is unaffected with an easy C6.

Holton 55 alto horn mouthpiece: after my experiences with all of the above, I had postulated that an American alto horn mouthpiece with a shallower bowl cup might be the perfect solution. So far, I think my hypothesis was on the money. It has a nice fat tromboney sound like the bigger options above, but I can still play comfortably up to around high Bb and it works nicely all over the horn without too much effort (unlike any of those others).

Although I still have not tried every possible kind of mouthpiece yet, I feel that I’ve found a solid formula for both sound and playability that gives the instrument a unique trombone voice: American alto horn mouthpiece for classical, marching mellophone mouthpiece for jazz. That said, there are a few more options I still have to explore the next time I own a soprano:

German flugelhorn mouthpiece - German flugelhorns use a shank essentially identical to a trumpet shank, so you can use them on anything with a trumpet shank (like soprano trombone). German flugelhorn mouthpieces are also generally not quite as deep as the dark, rich Denis Wick-style flugelhorn mouthpieces, nor are they as shallow and thin as Bach-style bowl cup flugelhorn mouthpieces. It could be a really nice middle ground that would mesh well with the soprano trombone, and given the history of rotary flugelhorns being used in their place, it seems like it would be a good fit.

Curry TF/ACB FX - these hybrid trumpet mouthpieces with deep flugel-like cups are an interesting option. I’m not very confident that they would be the right move, but considering how well the marching mellophone mouthpieces work I could be wrong.

Chasons hybrid trombone/trumpet mouthpiece - this is the kind of mouthpiece Wycliffe uses on soprano trombone. While I would love to try one of these, they are very expensive and I’m not motivated to spend that kind of money on a possible soprano trombone mouthpiece!

As you can see, I didn’t quite complete my soprano trombone mouthpiece safari. But I did get some excellent results that gave the instrument a proper soprano trombone voice, and I would encourage other soprano trombone owners to expand your horizons beyond trumpet mouthpieces to get the most out of your instrument.

Of course, there is also the question of what soprano trombone to buy if you don’t already have one. Fortunately, there are not too many choices to be confused by and I’ll give you a quick summary of each.

Cheap Chinese sopranos - if you just want a soprano to mess around with for fun or to see if you have any interest in pursuing the instrument further, this is the tier you should be looking at. There are a million different brands, but you should ignore them all and buy the Thomann SL-5. Why? Because they are all the exact same instrument, and the Thomann is the cheapest by a significant margin. It’s VERY cheap, so if you really want a soprano and don’t want to budget very much for it your search ends here. Even used Chinese sopranos cost more than this.

Jupiter 314 - this was the most popular entry-level soprano when it was in production, as it came before all the cheap Chinese ones. They are no longer made, but you can find them used occasionally for around the same price as most new Chinese sopranos ($200-300). The Thomann is still much cheaper, but you probably won’t get a bad example with a Jupiter and it will hold its value better.

Carol Brass CTB-1005-YSS-Bb-L - In addition to being made by the good maker that is Carol Brass, the CTB-1005 is superior to any cheaper soprano for one big reason. All the Chinese sopranos and the Jupiter 314 are tuned via the tenon attaching the bell to the slide, which is the cheapest and worst method. The CTB-1005, on the other hand, has proper leadpipe tuning like a flugelhorn. As far as affordable sopranos go, it is far and away the best option. Its price varies depending on the retailer; it lists at $479 at Carol Brass of the Rockies, but $900 at Austin Custom Brass.

Carol Brass CTB-2005-GLS-GL - Carol’s mind-numbing alphanumeric naming scheme makes it seem like this should be a simple variation of the above soprano trombone, but this is actually a completely new model, recently introduced. Notably, it is pitched in G rather than B-flat! It uses the bell (including that big shepherd’s crook) from the maker’s Phat Puppy flugelhorn, and does sound much more flugel-like than most soprano trombones. A very interesting new development for the soprano!

Carol Brass CTB-2005-GLS-GL soprano trombone in G - see the full product page here

Miraphone 63 - this is the only factory professional-level soprano trombone on sale today. I haven’t played one so I don’t know how well it plays, but at $2300 this is really only an option to the most dedicated players.

Thein - this is probably a soprano that is really worth the money, but it is a LOT of money. If you absolutely must have the very best soprano money can buy, this is your ticket.

Custom - honestly, if you have a tech you trust and access to a cornet bell and a small bore trombone slide, I would rather get one custom made than buy a cheap factory instrument. You can make it whatever bore you want, whatever mouthpiece shank you want, add a valve if you want, and so on. It will probably play at least as well as a new Chinese instrument and be infinitely cooler.

Vintage Used - Occasionally, used sopranos from the early 20th century will turn up for sale online, often for prices in the new Chinese range. If they are in decent shape and going for the right price, they could be a good option. The one model I would avoid is the DEG/Getzen with the ultra-narrow handslide.

Minick - The famed brass maker Larry Minick made a few sopranos, including a few with valves for studio players. They are extremely rare today.

Wessex PB455 - The PB455 was a large bore (.500”) soprano with F attachment that Wessex only very briefly offered on their website. It was removed almost immediately due to quality issues. They sadly never fixed the issues and relaunched the product, though the owner of Wessex did tell me a few years ago that you could still custom order one if you wanted.

Brazilian Slide Bugles

In low brass circles, the topic of “slide euphonium” is occasionally brought up. Do they exist? Is it even physically possible?

The answer is usually “no” to both counts, and to be fair that’s technically correct if you’re trying to preserve the euphonium’s conical bore throughout. You could try a variation of E.A. Couturier’s conical trombone slides I suppose, but that would be unlikely to even be functional on a wide-bore cone like a euphonium.

The real, better answer is “kind of.”

A euphonium with a full-length 7-position slide is impossible. However, you could easily make a “slide euphonium” by putting an appropriately-sized cylindrical handslide with 1-3 positions early in the tubing. It would physically work, but the euphonium would be drastically less conical than a valved one. This would likely result in an intonation nightmare and a sound noticeably different from a normal euphonium, not to mention understandable debates on whether it still qualifies as a euphonium at all.

What’s more interesting than all that is that the instrument just described not only exists but is performed with regularly. Welcome to the wacky world of the Brazilian cornetão gatilho, or slide bugle.

These instruments are used in Brazilian carnival music in sizes from soprano to bass. The two largest members of the family are slide euphoniums!

There is almost nothing about these instruments on the English-speaking Internet, which is the main reason I wrote this article. What I have been able to find from Brazilian websites are the following instruments:

Corneta Gatilho Soprano

Pictured is a Weril B-flat model, but these come in B-flat, F, and E-flat. Whole step handslides seem to be universal.

Corneta Afinação Soprano

These instruments have both a short handslide and a whole-step piston valve. Unlike the slide-only sopranos, these seem to only be in B-flat.

Cornetão Gatilho Contralto

The least common ones out of those I could find online. This one (by Weril) is in E-flat.

Cornetão Gatilho Tenor

These are mostly in B-flat, but I have seen them in alto F as well, still taking a trombone mouthpiece. They are often furnished with only half-step slides, though this Weril model seems to have a whole-step slide.

Cornetão Gatilho Eufônico

Slide euphonium!

Bombardino De Marcha Sem Pistos

Literally “marching euphonium without pistons”, this is the bass of the slide bugle family. Although it sounds like a euphonium and plays in the same range, it is pitched in bass F or E-flat.

There are also cornetão with just one whole-step piston valve and no handslide (including in odd keys like G), and others with no handslide OR piston. However, it seems that the cornetão gatilho with just the slide is the standard.

Far be it from me to just talk about these instruments. Here is a Facebook video of them in action. This band looks like it includes sopranos, tenors, and the bass euphoniums (which seem to be in E-flat based on the slide positions). Although it presents more intonation challenges, I think the short handslide is an intriguing solution to the “make bugles be able to play more notes” problem that North American drum and bugle corps tackled in a different way.

This is the extent of what I’ve been able to find online (as a non-Portuguese speaker) about this family of instruments. If you are Brazilian and know more about them or have experience playing them yourself, please feel free to reach out to me! I would love to learn more about the history and common practice of these instruments.

Ode to a Blue House

On September 1st, 2018, I and my overloaded Subaru completed an arduous 3-day drive across the country as we crested a hill and came to a stop in front of this blue house. Moments after getting out of my car and taking in the fact that I was now officially a resident of Los Angeles, I was standing in a small empty bedroom on the second floor of this house, which ended up being my home for the next four and a half years.

Yesterday, on January 1st, 2023, it finally hit me that I was really leaving when I took my last possession out of that room and was left with that same empty room from 4.5 years prior staring back at me.

I had expected to feel a lot of things when it hit me: excitement for my new place and the journey ahead, relief that I was finally done moving things out of there, and maybe a bit of nostalgia for the time I spent in that room. Instead, I was greeted with a sharp pang of sadness.

I grew up in a military family, so we moved around. When we finally settled in the DC area, it was the first place I grew to know as “home”. But we also moved houses within the area years after we initially got there, so the longest I ever spent in one house before going off to college was about 3 years. In college I bounced around dorm rooms and off-campus apartments every year, and left for the West Coast having lived in 7 different spots in 7 years. What this means is that the 4.5 years I spent living in the Blue House on the Hill is by far the longest I have ever lived in one residence. This turned out to not be as easy to say goodbye to as I originally thought.

There are many practical reasons why I moved and why I’d been looking for a new place for a long time. But in the moment I saw the empty room, I forgot all of them and had to fight back tears as all of the memories came flooding back. How I started my Los Angeles journey in that room, calling my parents to tell them I made it safely and then walking to Guisados to get my first LA meal. All the nights in the house laughing or crying the night away with friends and housemates. Playing happy birthday on the roof as the party looked on from below:

…and many more, lots of which were preserved in the Polaroids we took in the moment.

In many ways, living in the house felt like living with a family - a family that at one time would go exploring on Bird scooters every Monday and cook a feast together every Wednesday. And though I am beyond excited for my new place and what lies ahead, I will always cherish the good times at the blue house and recognize its significance in the history of my life. After all, I started my LA career there, lived through a global pandemic there, and started living as my true self there. It’s impossible to overstate how important the Blue House chapter of my life was.

It’s going to be really hard not answering “Echo Park!” when somebody asks where I live. Because I lived there for so long compared to everywhere else in my life, it almost feels like I just left home for the first time. It’s going to take time to fully process and get used to, and I think a part of me will always feel like I belong there until I live somewhere else even longer. Echo Park almost feels like part of who I am. My time there was far from perfect and in truth I am glad to be out, but it was hugely important all the same.

So long, Echo Park. Thanks for everything.

…except the Dodger traffic. 🙄

Mutes

Brass instrument mutes are amazing tools and are lots of fun, but can be daunting for a new player or a composer to dive into. There are so many different kinds out there. If you’ve ever asked yourself “what mutes do I need?” or “what mutes can I write for?”, or if you’re just curious about mutes in general, you’re in the right place.

MUTE TYPES

Straight

The straight mute is by far the most commonly used mute in band and orchestra music, and is what you use when the part simply says “mute” or “con sord.” without any further description. In jazz it is less common than cup, Harmon, or plunger, but still good to have around for the Swing Era or David Baker charts that call for it. The modern default is a metal (usually aluminum) straight mute, but fiber and wooden straight mutes are also used in certain circumstances. In general, metal mutes sound the brightest, wooden mutes the darkest, and fiber somewhere in the middle. They are all noticeably different sounds, and occasionally a composer will specify the material of straight mute desired. Most of the time however, brass players will choose what straight mute to use on their own. It is common for trumpet players especially to own a few different straight mutes for different purposes.

The three most popular brands of metal straight mute for trumpets and trombones are Jo-Ral, Denis Wick, and Tom Crown. Any are good choices, but I tend to favor the Jo-Ral. Tom Crowns sound great but do not have a felt ring on the small end, making it much easier to put dents in your bell, and make a racket while doing so. Of course, those three brands are far from the only metal straight mutes out there. I have a Humes & Berg aluminum trombone straight mute that is wonderful, especially considering H&B is not really known for its metal mutes!

If you are a freelance trumpet or trombone player, it is a good idea to eventually pick up a Humes & Berg Stonelined fiber straight mute. Like its cup mute sibling, the H&B has a unique sound that is sometimes desirable in jazz. Nowadays it’s not nearly as common to need one as it once was, as metal straight mutes have become the accepted default even in jazz. That said, I have needed my H&B on few gigs, including one where the bandleader explicitly called for “Stonelined straight mute” in the part. Plus, they are very inexpensive so it won’t set you back that much to get one.

In the French horn world, the straight mute is the only mute ever called for. Unlike with trumpets or trombones, horn players typically always use wooden mutes as they match the instrument far better than the other types (though fiber and metal horn mutes do exist). Ion Balu makes a fabulous horn mute, but there are a few others (Marcus Bonna for example).

Cup

Cup mutes are the most common mute in big band jazz, and are the second most common (but a distant second) elsewhere. In jazz, the classic red and white Humes & Berg Stonelined fiber cup mute is the default, and nearly always the desired sound. Any jazz brass player absolutely must own a Stonelined cup mute.

While still ubiquitous in jazz for its unique sound, the H&B Stonelined is outdated (and can even be seen as amateurish) in the classical realm. In orchestra and band, the standard is the Denis Wick adjustable cup mute. This mute is a mixture of metal and fiber, and the cup can be removed to give a passable fiber straight mute. As any working classical trumpet or trombone player will have a Denis Wick cup mute on hand, writing for and specifying fiber straight mute is a safe bet. Additionally, as the Wick is an adjustable cup, writing for “tight cup” and other specific settings is also safe. Markings for “tight cup” do appear from time to time in jazz and Broadway shows, so jazz and commercial players will often carry a Wick adjustable cup in addition to their Stonelined. The Wick cup is not the only adjustable cup out there, and a player may prefer a different brand. But even if you use a different adjustable cup when you are the only player on your instrument, you should also have a Wick to match with a section. Matching mutes is advisable whenever possible.

There are cup mutes (as well as bucket mutes) for French horn, euphonium, tuba, and even British tenor horn and baritone horn. However, these are very rare and almost never called for, so it is best to avoid writing for them unless you are writing for a specific player or ensemble that has them. Similarly, as a player you will never show up to a gig with “cup mute” written on your euphonium part unless you play in a high-level British brass band that probably owns their own set, so you don’t need to buy one unless you want to. (And I don’t blame you for that…they sound extremely cool!)

Plunger

The humblest of mutes. There are plenty of specialty “plunger mutes” out there made of metal, fiber, or rubber, but the best plungers are still the bendy red ones from a hardware store. This also means they cost literally a dollar or two, so no player of a bell-front brass instrument should ever be without one. If you are playing Ellington and similar older big band music, you may need a pixie mute (typically an H&B Stonelined) to compliment your plunger.

Harmon

The Harmon mute is so named (with a capital “H”) because the original comes from the Harmon brand. Also called a “wah-wah” mute, the Harmon has a very unique sound with or without the stem. (As a composer, when writing for Harmon you should always specify “Harmon mute - stem in” or “Harmon mute - stem out” in the part. Or even “stem extended” if you’re really daring!) Although there are Harmon mutes for trombone and bass trombone, they are used very rarely. They sound very different from the trumpet Harmon, which is extremely common in jazz.

In jazz, the Harmon is almost never used with the stem, so much so that big band charts often don’t specify stem in or out - it is always assumed the stem is out. You can find stem in or out in Broadway shows, and in the rare occasions when Harmon is called for in classical music, it is usually with the stem in. There are quite a few trumpet Harmon mutes out there, including the original Harmon B Model. The Jo-Ral “bubble mute” Harmon is likely the most popular, and plays easier than the original Harmon. Jo-Ral also makes a bubble mute for flugelhorn! Needless to say, it is very unnecessary like all flugelhorn mutes…but it is very cool regardless.

For composers, writing for trumpet Harmon is normal in jazz, and fairly safe in band or orchestra. It is a standard mute in the trumpeter’s quiver, and only trumpet players who ONLY play classical might not own one. Writing for trombone Harmon is more risky, as many trombone players don’t have one. But plenty of contemporary orchestral and trombone choir music has made extensive use of trombone Harmons, so there is certainly precedent for it.

Bucket

The bucket mute is an interesting beast. Much like the cup mute, the Humes & Berg Stonelined bucket (called the Velvet-Tone) is still desirable in jazz for the sound. However, the Velvet-Tone is by far the most cumbersome and time-consuming bucket mute to attach and remove. This is not good for things like Broadway parts which are littered with notoriously quick mute changes, so trumpeters and trombonists usually start with a quicker bucket mute like the Jo-Ral and pick up an H&B later. The reason for having both is that the Jo-Ral bucket especially sounds VERY different from the H&B. This effect is most pronounced on trumpet, but present on trombone as well. The Jo-Ral bucket sound can be desirable (Wynton Marsalis often uses one when soloing), but it is generally not the desired sound for jazz section work.

Solo-Tone

In my opinion one of the coolest mutes out there, the solo-tone makes you sound like you’re playing through an old Gramophone. It is an acoustic “lo-fi” mute! However, it is also mostly absent from a trumpet or trombone player’s needs; the one place where Solo-Tone is frequently called for is Broadway, so if you play a lot of musical pit gigs, you’ll need to pick one up. It is generally a mute that brass players will not own otherwise, but I think more people should as it’s a lovely sound. The original Solo-Tone mute was made by Shastock and original ones are rare and fetch high prices, so most players use a new production mute made by one of a few brands such as Humes & Berg, Emo, TrumCor, Walt Johnson, and Warburton. If you don’t have a Solo-Tone mute and a part that calls for one lands on your stand (which can be marked “Solo-Tone” or “wood mute” in shows), use a Harmon mute with the stem in as a substitute.

Practice

Practice mutes are designed to make your sound as quiet as possible, so you can practice in places you otherwise would be too loud to play in (hotels, apartments, warming up backstage, etc.). There are a ton of practice mutes out there, and which one is best comes down to personal preference. They are not intended to be performance mutes, and don’t give a pleasing tone quality to be used as one in my opinion. Still, that hasn’t stopped some contemporary composers from writing for practice mutes in their brass parts. Practice mutes range from expensive and clever mutes like the Yamaha Silent Brass series, to DIY practice mutes made from a $2 Renuzit air freshener. I have both and several in between, and they all have their place. If you’re looking for a cheap practice mute (that isn’t made from an air freshener), I use and heartily recommend the Pampet practice mutes from Amazon. They are very affordable at $19 (trumpet) and $20 (trombone), and I prefer them over many much more expensive practice mutes.

Whisper

Whisper mutes are rare. Few manufacturers make them (Bremner and Emo are the two I know of) and not much is written about them. They are essentially practice mutes adjusted to be legitimate performance mutes that are louder and have better tone quality than a real practice mute, but can also be used as a practice mute in a pinch. I have never seen a whisper mute explicitly specified in a part, but it’s probably out there.

Buzz

Originally a model from Humes & Berg called the “Buzz-Wow” that is now very rare, the buzz mute essentially makes your instrument sound like a kazoo. Hirschman currently makes a buzz mute for trumpet and trombone called the Chicago Stinger, and you can get buzzers on Huber’s straight and pixie trumpet mutes. Daniel Schnyder’s subZERO bass trombone concerto calls for one, and performers of the piece have made their own using an old cone-shaped mute and a few kazoos. The legendary vintage trombone guru DJ Kennedy also made a few in a similar way.

Derby

Also called a “hat mute”, this kind of mute was originally an actual derby hat hung from the music stand or manually operated like a plunger. Nowadays players usually use actual derby mutes designed for the purpose, but apart from period jazz ensembles it is rare today for hat mutes to be used. Typically “in hat” instructions are ignored or faked by simply pointing the bell into the music stand. Although hats show up quite often in Swing Era big band charts, owning your own derby mute is not very common.

Others

While the above mutes cover anything you could possibly be asked to play, there are a few other types of mutes out there. These include the Emo megaphone mute, the Humes & Berg Stonelined 127 satellite mute, and a few custom homemade mutes. The aforementioned DJ Kennedy had a few trombone mutes made out of trumpet bells (“Trump-O-Tone”) and clarinet bells (“Clari-Tone”) that offer a unique sound. I own a Clari-Tone that I bought from DJ, and it sounds like a cross between a straight mute and bucket mute.

FIRST MUTES

If you are just starting your mute collection, these are the types of mutes I’d recommend.

Trumpet (band/orchestra): Jo-Ral aluminum straight mute, Denis Wick adjustable cup mute

Trumpet (jazz): Humes & Berg Stonelined cup mute, Jo-Ral bubble mute, hardware store 4” sink plunger

French Horn: Ion Balu or Marcus Bonna wooden straight mute

Trombone (band/orchestra): Jo-Ral aluminum straight mute, Denis Wick adjustable cup mute

Trombone (jazz): Humes & Berg Stonelined cup mute, hardware store toilet plunger

Bass Trombone (band/orchestra): Jo-Ral aluminum straight mute, Denis Wick adjustable cup mute

Bass Trombone (jazz): Humes & Berg Stonelined 199 Mic-A-Mute, hardware store toilet plunger

Euphonium: Denis Wick aluminum straight mute

Tuba: Denis Wick aluminum straight mute

ESSENTIAL CAREER MUTES

These are the mutes essential for any gigging freelance brass player. My brand recommendations are in parentheses.

Trumpet: metal straight (Jo-Ral), fiber straight (TrumCor), fiber cup (Humes & Berg Stonelined), adjustable cup (Denis Wick), Harmon (Jo-Ral), plunger (4” hardware store), bucket (Humes & Berg Stonelined Velvet-Tone), solo-tone (Shastock or Humes & Berg Stonelined Clear-Tone)

French Horn: wooden straight mute (Ion Balu or Marcus Bonna), stop mute (Tom Crown)

Trombone/Bass Trombone: metal straight (Jo-Ral), fiber cup (Humes & Berg Stonelined), adjustable cup (Denis Wick), plunger (hardware store), bucket (Humes & Berg Stonelined Velvet-Tone AND a quicker one, such as Jo-Ral)

Euphonium: straight (Ion Balu)

Tuba: straight (Schlipf)

MUTE COMPATIBILITY

If you’re into weird brass instruments as much as I am, you’ve probably thought about using them with mutes. Here are all the compatibilities I’ve found.

Bass Trumpet: small trombone or flugelhorn mutes (which one works better depends on the model)

DEG Alto Cornet: flugelhorn mutes

Dynasty G Soprano Bugle: NOT most trumpet mutes (throat is too large!)

Getzen Frumpet: bass trombone mutes

Flugabone: small trombone mutes

Kanstul G Alto Bugle: large trombone mutes

Marching Mellophone: tenor or bass trombone mutes, depending on the specific mute

Mellophonium: tenor or bass trombone mutes, depending on the specific mute (except plunger and wa-wa effects on a Harmon, because the reach is too far)

Soprano Trombone: some trumpet mutes

MUTE RECIPES

Oboe substitute: trumpet (C or E-flat) with wood or fiber straight mute

English horn substitute: flugelhorn with cup mute or trumpet (B-flat) with dark-sounding cup mute

Bassoon substitute: trombone, bass trombone, or flugabone/valve trombone (depending on passage) with cup mute

Clarinet substitute: trumpet with bucket mute (ideally wood)

MUTE MANUFACTURERS

aS

Bach

Best Brass

Beversdorf (rare vintage metal straight mutes for tenor and bass trombone, with the darkest sound of any metal straight mute I’ve heard)

Brass Spa

Bremner/sshhmute (practice mutes and a whisper mute)

Care for Winds

Charles Davis

Clary Woodmutes (wooden trumpet mutes)

DEM-BRO

Denis Wick

Eazy Bucket (H&B-style bucket mutes that are easier to attach/remove)

Emo (a wide range of affordable plastic mutes)

Engemann (traditional wooden mutes)

Facet (unique wooden mutes)

Faxx

Harmon

Hawkins

Hickman

Hirschman (buzz mutes and plunger mutes)

Horn-Crafts Mutes

Huber Mutes

Humes & Berg (creators of both the iconic Stonelined red-and-white fiber mutes and a line of “Symphonic” aluminum mutes)

Ion Balu (wooden mutes)

Ira Nepus (innovative Softone rubber mute that can be a bucket or practice mute)

Jo-Ral (originally Alessi-Vacchiano)

Marcus Bonna

MG Leather Work

Michael Rath (metal trombone and bass trombone mutes)

Mike McLean (a full range of fiberglass mutes for all British brass band instruments)

Mutec

Okura+mute

On-Stage

Pampet (affordable practice mutes)

Peter Gane

P&H

Pöltl (Esser Dämpferbau)

Powerstopf (French horn stop mute)

Pro Line (light fiber mutes)

ProTec

Ray Robinson (a vintage mute maker with highly desirable fiber jazz mutes)

Rejano (trombone practice mutes)

RGC Mutes

Schlipf (tuba mutes)

Shastock (makers of the original Solo-Tone)

Soulo

Thomann

Tools 4 Winds

Tom Crown

Trapani (a new high-quality 3D-printed mute company)

TrumCor (high-quality black fiber mutes used frequently by orchestral trumpeters)

Ullvén

Upmute

Vhizzper (practice mutes)

Voigt Brass

Wallace (a full range of metal mutes)

Walt Johnson

Warburton

Windy City

Yamaha (mostly known for the Silent Brass practice mutes, though they do make other kinds of mutes as well)

Valve Tuning Theory

There is a small tuba-oriented website that offers a fascinating valve tuning/fingering calculator for download. It will take the valve tubing lengths (as proportional to the overall length of the instrument) you input and spit out every possible fingering, what pitch would result, and how close to in tune that pitch would be. As someone who enjoys brass instruments, numbers, and spreadsheets, I had to download it right away. Since then, I’ve spent many hours trying countless theoretical valve combinations and recording the results. I would hate for my findings to only exist in my downloaded copy of an Excel spreadsheet, so here we are.

It is important to clarify that the calculator only models the 2nd partial, as it was designed originally to figure out what valve lengths work best for low register intonation on tuba. On a real instrument, if the tubing is cut to the correct length the modeled tuning tendencies will also be correct. However, this accounts only for that 2nd partial, and all brass instruments have partials less in tune than others. So things like the viability of alternate fingerings in the upper register can’t be predicted. Additionally, all brass instruments have a zone in which the note you’re aiming for locks in, called a “slot”, rather than fixed points at which each note sits. It is still up to the player to tune the instrument and individual valves properly, and then hit the center of the slots to play in tune.

That said, a theoretically-perfect valve configuration will make the player’s job much easier, and eliminate the need to manipulate valve slides while playing or lip out-of-tune valve combinations into tune. Thus the goal for fully-chromatic instrument is to find a configuration where every note in the 2nd partial all the way down to (at least) the note a half-step above the 1st partial fundamental is as close to perfectly in tune as possible. On a 9’ tenor B-flat instrument such as euphonium, this means Bb2 down to B1 (with Bb1 being the fundamental). Of course, fingerings will also work the same in higher partials, with the player only having to compensate for the individual instrument’s partial quirks. (Typically: 3rd partial slightly sharp, 6th partial very sharp, 7th partial unusably flat. The other partials vary more between individual instrument models, such as the 5th partial being flat on some trombones and sharp on others.)

It is also important to clarify that on some instruments, especially smaller ones like trumpets, it is often much more practical to have a slide kicker or two than have a totally different valve system. This is why the standard 3 valves are so ideal on trumpet and flugelhorn, despite being a very imperfect configuration in the absence of slide kickers/triggers. But for large instruments like tubas, getting the valve configuration as close to as perfect without manipulation is more valuable.

Let’s start with six valves. The obvious disadvantage to six valves is that you have a lot of valves to work with. Not every instrument will have room for them, and of course more valves = more cost. However, six valves provide multiple near-perfect configurations that any fewer valves cannot match.

The first and most logical system is the standard 6-valve setup. This is the setup seen on all modern 6-valve F tubas, and consists of 3 normal valves (whole step, half step, 1.5 steps), normal 4th valve (perfect 4th), a long whole step 5th valve, and a long half step 6th valve. (A "long step” is one that is in tune with the 4th valve down. So on a B-flat instrument, a long whole step would be a whole step in F.) When plugged into the calculator, the most optimal fingerings end up as follows:

For everything in this calculator, I set it to a 9’ B-flat instrument such as euphonium, as that is what I am the most familiar with. Additionally, the 3rd valve is always tuned for 2-3 to be in tune (slightly lower than tuning to just 3) except where noted.

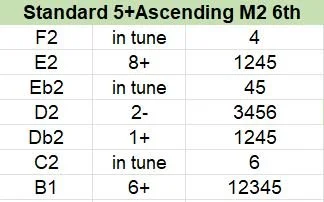

I was most concerned about the 4th valve register, as the first 3 valves are a known entity and work well enough. They aren’t perfectly in tune, but brass players are used to compensating for that. So, although the calculator spits out every possible fingering starting at the first note below the open 2nd partial (in this case A2) and goes down as far as the valves will take it, I only input the optimal 4th valve register results for the sake of clarity. These are not the ONLY possible fingerings, but the most in-tune. The left column shows the note, the right column shows the fingering, and the middle column shows how close to in tune that fingering is. “9-” means the note is 9 cents flat, while “1+” means it’s 1 cent sharp. For reference, the standard 1-2 fingering is 10 cents sharp, so these are all well within acceptable deviation. Not perfect, but close enough. Adding up all of the middle column (in tune = 0) gives a deviation score of 19.

As if it wasn’t already not good enough, you can further optimize this configuration. By shortening the long half step 6th valve by about 1.39”/35.39mm so that 13456 is in tune, you get the following beautiful result:

This has a deviation score of just 7 and is the closest to perfection that I have found. It requires no new fingerings and is so close that it might as well be perfect. You could even make the 6th valve dependent on the 4th or the 1st if you wanted.

To be frank, you could stop reading here if you just wanted to grab the best solution and run. It’s already standard, it’s near-perfect, it just works. But we’re just getting started!

The next 6-valve configuration we’ll look at is one of my favorites.

This configuration uses the same first 5 valves as the standard 6-valve arrangement, but the 6th valve is an ascending whole step. Ascending valves are relatively rare, but can be very useful. Although less familiar than the unoptimized standard 6-valve setup, this setup scores a slightly better deviation score of 17.

Now, if you have an instrument that you want to punch well above its weight (or more accurately length) in terms of low-end prowess, it turns out the old French tuba in C (as written for in Ravel’s famous orchestration of Pictures at an Exhibition) had a very competent valve system for doing just that. Taking that template and updating it to use a modern 3rd valve (1.5-step instead of the old 2-step), and you get the following:

To clarify, this configuration includes 4 normal valves, a long half step 5th valve, and a perfect-5th 6th valve. Apart from the 1.5-step 3rd valve, it is the same as the original French instruments. As you can see, it takes you far lower than a modern 6 valve setup could, thanks to the quint valve. It’s not the most in tune in that pedal-replacement register, but we can improve that by making the 5th valve a long whole step instead of a long half step, thereby resulting in a standard 5-valve configuration plus the P5 6th valve:

While neither of these setups are as ideal as the standard 6-valve setup, higher-pitched instruments intended to still be able to play commandingly down to the pedal register and below could benefit from such a setup. The Half-Modern setup (long half step 5th) works better above the bonus pedal-replacement register, with a deviation score of 16 above Bb1, while the Modern setup (long whole step 5th) works better in the bonus pedal-replacement register but significantly worse above it (scoring a deviation score of 26). Still, even 26 is very usable in the real world.

These four configurations are the only ones that I classified as optimal, denoted by the green background underneath the configuration name. Any of them would be an excellent choice. There were unsurprisingly some excellent 7-valve configurations, but they didn’t provide any real advantage over the best 6-valve setups so I didn’t consider them optimal. Here are most of the other 4, 5, 6, and 7 valve configurations I tested and their derivation scores (all ignoring any bonus pedal-replacement notes):

Modern French Tuba 6 with ascending whole step 3rd valve (a la true French double horns): 26 (great except for D2, at 17 cents sharp)

Standard 6+Long 1.5-step 7th (aka 3 normal valves, normal 4th, and 3 long valves in tune at the length of the 4th valve; functions the same as a full double instrument but with more fingering possibilities): 9 (almost perfect, but…the optimized standard 6 is even better with one fewer valve. Still, if you have 7 valves lying around…)

3+3 (3 normal valves, 3 long valves; aka the setup above but without the 4th valve): 45

Modern French Tuba 6+ascending whole step 7th: 13 (SO not worth the trouble)

Modern French Tuba 6 with ascending whole step 5th: 15

Modern French Tuba 6+long half step 7th, tritone 7th, or Major 3rd 7th: they became clear it was so not worth it I didn’t even progress far enough to get a derivation score

Standard 5 valves (long whole step 5th): 48

Standard 5 with ascending whole step 3rd: 38

Standard 4 valves: 77 (and that’s not including the non-existent low B and so-bad-it-might-as-well-be-non-existent low C!)

Standard 4 with ascending whole step 3rd: 41 (no low D or Db)

Standard 4+perfect-5th 5th valve: 59

Standard 4+ascending whole step 5th: 66

Standard 4+tritone 5th: 65

Standard 4+Major 3rd 5th (2 whole steps): 96

Standard 3+P5 4th+ascending 5th: 54

Standard 3+tritone 4th+ascending 5th: 50

Standard 3+Major 3rd 4th+ascending 5th: 87

Standard 3+tritone 4th: 88 (…and still no low B)

The moral of the story is that I couldn’t find a single configuration with less than 6 valves that was any good. The standard 5-valve setup with the long whole step 5th was the best of the lot, but still several dimensions behind any of the good 6-valve setups. The situation with only 4 valves was even more dire. Regarding possible 4 to 7 valve configurations starting with the normal first 3 valves, I think we can pretty safely close the book with our knowledge of the Four Good Tunings™.

…however…

…what if you DON’T start with the normal first 3 valves?

While pondering what one could do with a 2-valve G bugle to make it fully chromatic in a way that’s not annoying, I had an idea and spontaneously invented a beautiful 2+2 valve system that has the same range as a normal 3 valves and eliminates the need for any slide kickers or adjustment.

First, let’s take a look at the standard 3 valves for comparison. When the 3rd valve is tuned to 2-3, you have 0, 2, and 1 in tune, 12 at 10 cents sharp, 3 at 16 cents flat, 4 in tune, 13 at 15 cents sharp, and 123 at 38 cents sharp. It is hardly a good system on paper, with a derivation score within that partial of 79. Of course, kickers solve all of this…but not every instrument has room (physically or ergonomically) for even one kicker.

My 2+2 system works as follows. The first two valves are your standard 2 valves (whole step and half step), as found on any 3 valve set with the 3rd valve ignored, or any 2-piston G bugle. The next two valves are also a whole and half step to start, but tuned very specifically. The third valve is tuned so that 123 = an in-tune 1+3 fingering on a normal valve set. This means lengthening the slide from its standard whole step position by about 3.22”/81.75mm on a 9’ B-flat instrument. The fourth valve is tuned so that 124 = an in-tune 2+3 fingering on a normal valve set. This means lengthening the slide from its standard whole step position by about 1.93”/49.10mm on a 9’ B-flat instrument.

The result?

A derivation score of 12.

Additionally, 2-valve G bugles have a kicker on the 1st valve slide that kicks inward, in order to bring the 7th partial 1st-valve note (which is extremely flat, and able to be completely avoided on 3-valve instruments) up to pitch. Given as the 2+2 configuration was designed specifically for 2-valve G bugle valve sets that would otherwise be useless, it is likely then that a 2+2 instrument would have at least one inward kicker on the 1st valve. On the data above, 1+2 is listed as the fingering for G2 because it is the closest to being in tune. As it is sharp and not flat, an inward kicker wouldn’t help. However, 1+4 is another available fingering, which is 16 cents flat. The inward kicker, long enough to bring a note a full quarter step flat into tune, would undoubtedly be able to bring that 1+4 fingering up to pitch.

Having this 2+2 valve block as a base opens up another world of possibilities with additional valves. So far I have run through 15 configurations with 6 valves (2+2+2?), and while none are perfect, nearly all of them are very good and several are among the closest to perfection of any configuration I’ve found thus far.

Of course, none of those configurations is that practical. Even just the 2+2 system requires learning a new fingering pattern, even though it is arguably more logical than the usual 3 valve pattern. The basic pattern of the left hand 3rd and 4th valve is identical to the right hand 1st and 2nd. But the 2+2 system is only worth doing over a standard valve set in a very specific circumstance involving 2-piston G bugles.

What makes it even more viable for that context is that the 3rd and 4th valves can be made dependent of the 1st and 2nd. Since every standard fingering involving 3 or 4 has both 1 and 2 down, 3 and 4 can be inset in those valves’ tubing. What this means is that you could set both valves in alternate slides that plug in to the existing valves’ valve slides, without modifying the original bugle in any way. And because the valves are dependent, the bugle would feel exactly the same to play until you used one of the additional valves.

Eventually, I would love to be able to 3D-print 2-valve sets for G bugles and sell them so that players could slot them into their 2-valve bugles whenever they needed the missing pitches. A +2 valve set would drastically expand the musical possibilities of a 2-valve bugle, and would do so without altering the original instrument in any way. What’s not to like?

Cellophone

The cellophone is one of the rarest and least-known competition bugles in G, made by DEG Dynasty in 1984. It is really just a flugabone in G, and was based on Dynasty’s B-flat flugabone (which they called a “Marching Trombone”), itself a derivation of the original King 1130 flugabone.

The principal production run of the cellophone was a single group of four 2-valve instruments, built for and used briefly by the Phantom Regiment drum and bugle corps. No further 2-valve cellophones were built.

A catalog spread showing off the 2-valve cellophone.

However, there are currently also a handful of known 3-valve cellophones, which were presumably made for the European market.

One of the ultra-rare 3-valve Dynasty cellophones.

If you really want a cellophone, the easy way would be to get a normal B-flat flugabone and add tubing to get it down to G (as this is what Dynasty did). For the 2-valve cellophone experience, you could even just clamp down the 3rd valve and tune the first two valves appropriately. Dynasty flugabones rarely show up for sale (and the King flugabone pattern is not the only model of Dynasty marching trombone out there!), but fortunately there are quite a few King 1130s floating around. The King is likely the better instrument, but a less authentic base for a cellophone.

I have not played or heard a cellophone myself, so I can’t comment on the sound or how it compares to my King flugabone. But based on how B-flat marching baritones compare to the ones in G, I can’t imagine it’s a huge difference.

Nirschl Mellophone

You’d be forgiven if you didn’t know that Nirschl, the esteemed German brass instrument manufacturer responsible for lots of enormous 6/4 CC tubas, once sold a marching mellophone. There is very little record of the instrument on the Internet; its entire presence consists of a Middle Horn Leader review, a discussion in episode 73 of the MelloCast podcast, an old Reverb listing, and a couple of derelict shells of online store pages for the instrument from over a decade ago (listed price was $899!).

The instrument is called the E-102 (E-102SP in silver plate), and while it was not actually built by Walter Nirschl, it is still an intriguing instrument. Even among mellophone enthusiasts this instrument is usually forgotten, if it was ever known about to begin with. It might as well not exist…right?

Nirschl E-102SP

Well, I suspect the primary reason it gets forgotten as a mellophone is because it’s not very good at being one. In fact, it’s so bad at being a mellophone that I think it being marketed as one was a mistake. The reason for this deficiency is the bell; one of the mellophone’s defining features both visually and sonically is the extra-wide 10” or larger bell flare. Nirschl decided to skip this feature entirely, instead giving it a relatively small 8” bell. In a way, this makes it somewhat of a poor man’s alto flugelhorn or marching alto.

So, how does it work as an alto flugelhorn? The answer is, unfortunately, not very well. Using the mouthpiece from an alto horn or alto trumpet results in a woefully flat instrument - with a Denis Wick, the instrument is so flat it’s almost down a whole step to E-natural (but not quite low enough that you can actually use it that way). This is a problem shared with the Kanstul KAH-175 alto bugle in G, though that instrument is of infinitely better quality. The Kanstul is at least in tune when you use a marching mellophone mouthpiece like a Benge Mello 6, which is what it was designed for. The same cannot be said of the Nirschl E-102, as even with the shallowest marching mellophone mouthpiece it still plays flat with the main tuning slide all the way in!

Weirdly, the mouthpieces I found to work best with the Nirschl don’t even have the right shank: a French horn mouthpiece and an antique Conn circular mellophone mouthpiece. Despite not seating in the Nirschl’s mouthpiece receiver at all, they gave the best sound and intonation out of all the mouthpieces I had, and I gave its new owner the old Conn mouthpiece when I sold it. That mouthpiece never worked well in any of my circular mellophones!

I can see now why the Nirschl E-102 never took off. In its factory state, it is thruthfully as useless as the Getzen frumpet, and bears the odd distinction of being the only marching mellophone (or mellophone-adjacent object) I know of that actually works better with a horn mouthpiece. With marching mellophone or alto horn mouthpieces, your only real option is to get the horn lengthened to E-flat, as the main tuning slide has no room to shorten up to pitch with those mouthpieces.

If you really want a small-bell mellophone in F, I’d recommend waiting to get lucky and find a Kanstul KMA-275 marching alto. It’s everything the Nirschl wishes it was and more.

Kanstul KMA 275 marching alto in F

Yamaha Mellophone Sisters

The Yamaha YMP-200 series of marching mellophones is the standard by which all other marching mellophones are measured. It is well-known to be arguably the best marching mellophone there is, so it often commands significantly higher prices on the used market than any other brand. The current model, the YMP-204M, is the pinnacle of mellophone design; however, even the first YMP-201M is an excellent instrument leaps and bounds ahead of most other marching brass.

However, the YMP-201M was not the first Yamaha mellophone. That honor goes to the rare and mostly unknown (at least in the West) YMP-201 (no M) circular mellophone.

On the left is my YMP-201; on the right is my YMP-201M. They’re sisters!

However, the 201M is not just a 201 re-wrapped to point the bell forwards; there are some significant differences. The 201 has a huge 12” bell and a small .449” bore, while the 201M has a more standard 10” bell and .462” bore. The 201 can play in F or E-flat just by rerouting the two tuning slides built into the instrument - no extra slides needed! (This was also a feature on certain York mellophones.) Meanwhile, the 201M only plays in F. The 201 also has the traditional cornet shank, while the 201M uses a trumpet shank like other marching mellophones. Despite the only difference in designation being a single “M”, the two instruments are completely separate designs.

They play and sound different, too. The 201M sounds like a marching mellophone should, has a fabulous upper register, and can sound like an alto flugelhorn with an alto horn mouthpiece. It is light, balanced, and easy to play. The 201 meanwhile has a smaller yet darker sound that blends with anything. While other circular mellophones have more colorful, interesting sounds (my 1925 Buescher 25 and 1918 Conn 6E come immediately to mind), the 201M could be the ultimate gigging circular mellophone. It plays in tune, it has fast modern valves, it has a transparent, chameleon sound, but it can still light up and is easy to play in all registers. It is not the most glamorous circular mellophone, but it just works.

It is also how modern it feels in comparison to all other circular mellophones that makes it as interesting as it is. It feels modern because it IS modern; it started production in the 1980s! From what I have been told by a Japanese source, French horns were too expensive for many school bands in Japan, so they used the traditional mellophone into the 1990s as a French horn substitute. Yamaha thus made the relatively affordable YMP-201 exclusively for the Japanese domestic market, hence why it is so rare in the West.

If you can find either a YMP-201 or any YMP-20xM for a good price, I would highly recommend it. Both are the most competent instruments of their type and can be played to any standard. I never thought my Conn 16E would step down as my primary gigging bell-front alto brass instrument, but once my 201M arrived I knew it had been dethroned. With a Hammond 5MP marching mellophone mouthpiece, the 201M is unbeatable.

Alto Cornet

The alto cornet in F or E-flat is a rare bird. The easiest way to get your hands on one (at least in North America) is to find a DEG model 1220 from the 1970s. This is tricky to do, because they are usually labelled as mellophones on sale ads. DEG themselves marketed the 1220 as a “marching alto/French horn”, but that is a very inaccurate description of the instrument. It is a true alto cornet in F, with optional E-flat slide. Over the years I have seen several come and go on eBay, and it seems that they were made with at least three different bell sizes. The one I owned had the smallest and most common size that I have seen, at about 6.1”.

The 1220 was manufactured for DEG by Willson, as were many DEG/Dynasty instruments in the 1970s. Willson also sold a (non-DEG-branded) version standing in E-flat in their home market of Switzerland; I would love to know if it was marketed there as an alto cornet, and which model came first. It has a trumpet shank, accepts flugelhorn mutes, and is not much larger than a standard B-flat cornet. Alto horn mouthpieces are the best fit, though I’ve also had good results with an extremely small trombone mouthpiece.

DEG 1220 alto cornet (bottom) next to Bach CR-310 B-flat cornet (top)

It plays very well, and despite overwhelming external similarities to the 1970s Dynasty III alto bugle (also made by Willson), it sounds noticeably different even when both are played with the same mouthpiece. The Dynasty III sounds like a big flugelhorn (which is essentially what it is) with a horn-like edge when pushed, while the DEG 1220 is all cornet. Noticeably brighter and easily colored, with a rocking low register and a secure high register that requires a good deal of effort above written high C (sounding F5). Unlike many uncommon alto brass instruments, the 1220 has lock-tight slots. Intonation is not perfect but easily manageable.

While I don’t believe the 1220 is much of a soloist’s instrument, it is a champion at playing in a brass section. It can blend seamlessly with trombones or flugelhorns, and I have used it very successfully in recording sessions to do just that. In a 6-part horn section consisting of 2 trumpets, flugelhorn, alto cornet, and 2 trombones, the alto cornet is the perfect middle voice. The Yamaha YMP-201 (non-M) circular mellophone has similar qualities, but the DEG 1220 is more convenient to bring to a session due to its very compact size and forward-facing bell. This also makes it an excellent desk instrument for the alto brass player, or even the low brass player.

In short, the DEG 1220 is an excellent instrument that any multi-brass player could find good uses for, especially in the studio. They don’t show up for sale very often, but they usually go for a few hundred dollars. You’ll have the most luck finding one hiding in the mellophone ads.

Meehaphone

The Meehaphone is an enormously rare breed of 2-valve competition bugle in G, built and used from 1987 to 1991. It was designed by Jack Meehan and Zig Kanstul for the Concord Blue Devils drum and bugle corps, in an effort to streamline their middle voice section from three types of G bugle (mellophone, flugelhorn, and French horn) to one.

The exact number built is not certain, but as the meehaphones were built by Kanstul specifically for the Blue Devils, it is likely that there were only enough made to fill out the corps’ mid-voice section. It seems that at the time the Blue Devils’ mid-voice was consistently 14 players, based on instrumentations noted in this Middle Horn Leader interview with Wayne Downey and my own studying of the relevant footage online. It is thus reasonable to conclude that there were most likely 14 production meehaphones built. There was also at least one prototype built in F with 3 valves, which is now owned by Bobby Pirtle and resembles a giant flugelhorn.

According to the late Ken Norman, the meehaphone has a bell flare identical to the Olds BU-10 and Conn 92L French horn bugles, mated to a 2-valve .415” bore flugelhorn body. It is essentially a bell-front field descant horn in G. At the time, Terry Warburton made custom mouthpieces for the meehaphones, labelled “Downey BD”. The Blue Devils used an all-meehaphone alto section for the 1987-1990 DCI seasons, and in 1991 they used 4 mellophones and 10 meehaphones. The meehaphones were shelved shortly thereafter when new 3-valve G flugelhorns from Yamaha arrived.

According to all accounts, they were the loudest alto bugle ever created. In fact, on the bell is stamped “MFL”, which does not stand for “Marching Flugelhorn” but “Mother F***ing Loud”! They had a darker sound than mellophones and projected very well, but notes above written G at the top of the staff (sounding D5) were very hard to center. Here’s the Blue Devils’ 1988 show on YouTube, with plenty of meehaphone action to go around. After 1991, the meehaphones fell off the map. Most of them were lost in a single shipment, which has never been found. There are only a handful whose whereabouts are known, and all but one are on display in various states of functionality in drum corps-related museums.

So, that’s the lore…now, here’s my practical experience.

Here is an original Kanstul meehaphone, serial #1028, that I had the privilege of owning for a while. It was previously owned by Ken Norman, and is the single known example not in a museum.

When played softly, it has a French flugelhorn-like quality to the sound, which makes sense considering the .415” flugel leadpipe and valve block. When pushed, it gets bright with a trumpet-like edge, but without what I would describe as the mellophone’s tearing metal zing. It’s a very interesting sound that’s clearly related to my other alto bugles, but at the same time standing apart from them.

But don’t let me just talk about how it sounds. Have a listen for yourself!

These clips were all recorded close-miced into a Cascade Fat Head ribbon microphone and SSL2 audio interface. The ensemble excerpt in particular provides a good summary of the meehaphone’s qualities…both good and bad. The notes above the staff live up to their squirrelly reputation; while I could play them effectively (I suspect thanks to my Conn 16E experience), it is certainly a treacherous register. In general the intonation isn’t the best, but it’s nowhere near the worst I’ve played either.

It’s important to note that I did not have an original Downey BD mouthpiece made by Terry Warburton for the meehaphones. Mine came with a Burbank F mouthpiece with a cylindrical shank, and while it worked I didn’t feel that it was an ideal mouthpiece for the instrument.

For more playing and practical information about the meehaphone, check out this video:

Meehaphone (left) next to Couesnon flugelhorn (right)

Frumpet

The Getzen model 383 Frumpet, or “French Horn Trumpet” as it was also marketed, is a unique alto brass instrument that can play extremely loud. It also accepts bass trombone mutes, and has decent valves and ergonomics.

That is everything good that can be said about it.

It was made from 1964 to 1985 and was another attempt at a marching instrument for French horn players. It has a .464” bore and plays in alto F or Eb, with the Eb slide playing a little better. It takes French horn mouthpieces, but the length and taper of the instrument are not an acoustic match for that and the result truly horrendous. It has shockingly bad intonation that makes the Conn 16E mellophonium seem amazing by comparison, and its anemic sound doesn’t make up for it. You can find them cheap on eBay, but they are painfully useless except to use as a base for a mildly interesting lamp.

UNLESS…

…you get it modified.

All that’s needed to turn the frumpet from an inconveniently-sized paperweight into a usable and interesting instrument is to swap the leadpipe for either an alto horn or trombone leadpipe. That way you can use bigger mouthpieces that actually work with the bore profile, eliminating the horrible intonation problems. If you take it a step further and also swap the weird bell for a small trombone bell, you have yourself a nice alto valve trombone. You can also lower it to C or Bb (with the new leadpipe/bell) and get a bass trumpet of sorts.

One thing that has not been tried yet to my knowledge is to keep the stock bell and horn leadpipe, but put a bunch of tubing on it to get it down to Bb or even low F, convert it to point up instead of out in front, and see how it works as the world’s jankiest Wagner tuba. I would very much like to try that.

Anyway, don’t buy a frumpet unless you plan to either turn it into a lamp, use it for parts or as soldering practice, or extensively modify it. And don’t spend more than about $100.

Alto Bugle

“Alto bugle” typically refers to a type of competition bugle pitched in G for use in drum and bugle corps. Of the four main types of mid-voice bugle used in drum corps history (mellophone, French horn, alto, flugelhorn), the alto bugle is probably the rarest type. Usually based on a G mellophone bugle but with a much smaller bell, they didn’t make a lasting impression on the field. However, they offer intriguing possibilities for use outside of drum corps as they are essentially big flugelhorns in G. (There were actual G flugelhorns in DCI as well, but those were generally standard B-flat flugelhorns with tubing added.)

Many alto bugles had 2 valves, as that was the rule in DCI until 1990. But there are a few models of 3-valve alto bugle that exist. These are as follows:

Dynasty III alto bugle (late 1970s): Likely the earliest 3-valve alto bugle to be made. As DCI was over a decade away from legalizing 3 valves, the complete Dynasty III bugle line was made (mostly by Willson) for the European market. Surviving examples of any type of Dynasty III bugle are extremely rare today.

Dynasty late-pattern alto bugle: This one was based on Dynasty’s existing mellophone design rather than a separate one, and was made in-house instead of by Willson. (The link calls it a flugelhorn bugle, but the Dynasty 3-valve flugelhorn bugle was a different beast made by slapping longer slides on a DEG Signature 2000 Bb flugel.)

Kanstul KAB-175 (‘90s, early model): This early model Kanstul alto bugle design resembles a smaller King 1120 marching mellophone, and as both instruments were designed by Zig Kanstul, is probably where the King design originated.

Kanstul 175 (late model): The later model used a totally new wrap and was made until Kanstul went out of business in 2019.

At one time I owned the only Dynasty III alto bugle I have ever seen. I haven’t been able to find any record of another individual example on the Internet. As none were made for the US domestic market, it may be the only one in the country. But rare G bugles have a funny tendency to show up in the weirdest places, so there could be others hiding in the States. I bought mine from Canada.

The following picture shows the Dynasty III, and also my DEG 1220 alto cornet in F for comparison, also made by Willson around the same timeframe and also very rare (but much more common than the Dynasty III!). It’s easy to see the family resemblance between the two instruments, even though they actually sound quite different.

Dynasty III G alto bugle (top) and DEG 1220 F alto cornet (bottom)

As the names imply, the alto bugle sounds like a flugelhorn, while the alto cornet sounds like a cornet. The alto bugle has a fat, dark flugel sound; the alto cornet has a brighter, leaner cornet sound. Both instruments play very well.

I also used to own an early pattern Kanstul KAB-175.

This instrument had a fabulous flugelhorn sound with a tenor horn mouthpiece (the same one I used in the Dynasty alto bugle and alto cornet). It was smoother and a shade darker than the Dynasty, and was a really refined sound. Which is not to say the Dynasty was rough; compared back to back with my Couesnon flugelhorn the Dynasty sounded quite close, just with a bit more beef in the sound. But the Kanstul took it a step further and makes the sound a little rounder and sweeter still.

Unfortunately, with this mouthpiece the instrument also played quite flat with the tuning slide all the way in. This is likely because it was designed around the classic Mello 6 marching mellophone mouthpiece. I have one of those, and putting either it or my Hammond 5MP marching mello piece into the Kanstul fixed the pitch and felt like the right match for the horn size-wise…but also entirely lost that lovely velvet flugelhorn sound. With the Mello 6 it predictably sounded like a more focused, direct marching mellophone. Very bright and trumpety, but much fatter than any trumpet (or G soprano bugle). There may be a niche for this sound, but I couldn’t find it and the big flugelhorn sound is really what I want in an alto bugle, so I eventually sold this instrument.

Physically, the Kanstul was fantastic. The valves were the best I’ve ever owned in any kind of brass instrument…lightning fast and whisper quiet. The instrument itself felt like it weighed nothing in the hand, owning to its light weight and great balance. I’m sure it would be a pleasure to march with, as instant horn snaps and moves are a piece of cake. The left hand grip is comfortable, there is a 1st valve slide kicker…it has everything you want. It feels like a massive leap forward in alto bugle design from the Dynasty, although the Dynasty’s super-compact form factor is definitely convenient. It is a shame then that the Kanstul doesn’t work out of the box with the tenor horn mouthpiece that the Dynasty happily accepts without issue; it could be that that early alto design was based around a larger, more tenor horn-like mouthpiece.

Although I never found a real use for the Kanstul and thus sold it, it’s one of the most enjoyable brass instruments I’ve ever played and I do miss it.

To hear the Kanstul meehaphone, Dynasty III alto bugle, and Kanstul KMB-175 alto bugle, check out this video:

The Marching Alto

Just as the mellophone bugle in G begat the marching mellophone in F, the alto bugle in G begat the marching alto in F. And as rare as the G alto bugle is, the F marching alto might be even rarer. Unlike the alto bugle and its limited use in DCI drum corps (especially in the 2-valve era), I know of nobody who ever fielded a line of marching altos. (If your high school or university marching band did, I’d love to know about it!)

These are the types of marching alto I know of:

Kanstul KMA-275 (late model): This is the F version of the late-pattern 175 alto bugle. I have yet to find evidence that Kanstul ever made an F marching alto version of the early pattern KAB-175 G alto bugle, or that any other maker made a smaller-bell version of their mellophone. It could be the only purpose-built marching alto ever made.

Nirschl E-102 mellophone: This horn wasn’t intended to be an actual marching alto, it was just Nirschl’s poor attempt at making a marching mellophone. It also works no better as a marching alto as it does as a mellophone…in fact, there is nothing it is good at. But it technically counts?

Andalucia AdVance Series Alto Horn: This is a current-production instrument in F, based on the Kanstul Meehaphone. The Meehaphone was a 2-valve instrument used from 1987-1991, and while it was built around a French horn bugle bell and was essentially a field descant horn in G, it successfully fulfilled the same role as an alto bugle (darker sound than a mellophone, but more projection than a flugelhorn).

As an aside, although they are not really marching altos, there are also bell-front alto horns, aka “solo altos”. These are mostly instruments from turn of the 20th century meant for alto horn soloists and shaped like large cornets. They are usually in E-flat and have much smaller dimensions and a smaller sound, as they are based on concert alto/tenor horns rather than marching mellophones. The Swedish maker Lars Gerdt had a marching tenor horn in E-flat listed on their website until recently.

Anyway, I recently acquired a Kanstul KMA-275 late pattern marching alto in F. It’s the first one I’ve ever seen in the wild; until it popped up for sale locally I had only ever seen the picture of it on Kanstul’s website all the way back in 2002.

The product page for the KMA 275 from Kanstul’s website circa 2002 (via the Wayback Machine).

My KMA 275.

While I knew the design had radically changed since the early pattern design, I assumed that this instrument would play pretty much like my KAB-175 did, just in F. But it actually plays quite a bit differently. Although it lacks the uniquely sweet sound the KAB-175 had with a tenor horn mouthpiece, the KMA-275 is actually usable with a tenor horn mouthpiece as it plays up to pitch without issue. In fact, the KMA-275 is happy with most mouthpieces you could throw at it.

Rather than describe all of these, here’s a short demo of some of the mouthpieces that work well:

I have to admit, although this instrument is very cool and as well-built and easy to play as you would expect, I would really love to find an early-pattern version of the 275. The KAB-175 was one of the most fun, satisfying instruments I’ve ever played and while this KMA-275 is excellent, it hasn’t made me unwilling to put it down yet. We’ll see if I get there.

Until recently I couldn’t find any existence of the early pattern mellophone/alto design in F at all, and I wondered if Kanstul only started making things other than G bugles after the late-pattern design was introduced. But an early-pattern Kanstul F mellophone recently showed up on eBay (for way too much money, or else I would have bought it already), so the early pattern in F has been proven to exist. But I am still in search of evidence of the smaller-bell 275 F marching alto in the early pattern.

The early pattern Kanstul 280 F marching mellophone from the eBay listing - stenciled as a Besson.

Mellophonium

The mellophonium is the primary ancestor of the modern marching mellophone. It is a traditional circular mellophone with the bell straightened out, and usually has a cornet shank. Even many brass players don’t know what a mellophonium is, and those that do (mostly Stan Kenton fans and alto brass nerds like myself) can be forgiven for thinking that “mellophonium” = Conn 16E. In fact, while the Conn 16E is by far the most famous model of mellophonium thanks to its use in the Stan Kenton Orchestra from 1960 to 1963, it is not the only one. There were lots of mellophoniums (mellophonia?) at the time: Holton M-601 and M-602, Reynolds ML-12, Courtois, Couesnon, Vox Ampliphonic, Glier (in E-flat), and more. You can even still buy a new mellophonium in 2022, courtesy of Amati Kraslice and their 16E-like AMP-203.

My 1969 Conn 16E mellophonium, with Conn 1 mouthpiece

Amati AMP-203 mellophonium

The mellophonium has a cool sound that is related to, but not quite the same as, a mellophone (either the traditional circular or bell-front marching variety). Stan Kenton’s electric 4-man mellophonium section inspired the creation of the mellophone bugle in G for use in competitive drum and bugle corps, which in turn directly led to the modern marching mellophone. The marching mellophone was also the mellophonium’s grave digger, because even the early Olds-pattern marching mellophones were much better instruments.

While not the only kind of mellophonium, the Conn 16E was the first (beginning production in 1957), is the most common to find today, and is the quintessential example of the type. Despite this, it is objectively a terrible design. It was built in F with an E-flat crook, so Conn decided to build the valve slides somewhere in between…too long for F, too short for E-flat! (It actually plays best in tune in E with the main tuning slide all the way out…I’ve played gigs with it that way!) Its intonation is a great struggle, it has extremely wide partials that are tricky to center, it has mediocre long-travel pistons, and it has a whiny and difficult upper register that requires tons of alternate fingerings to get anywhere near in tune. It is also an ergonomic nightmare, and every mellophoniumist has to find a grip that isn’t painful. The “standard” (as much as that word can be applied to anything mellophonium-related) grip is to hold it by the 3rd valve slide, like so: