The G Valve

For trombones with a single valve, a valve loop tuned to a perfect 4th below the open horn is the universal standard. This is the F attachment on a tenor or bass trombone, or Bb attachment on an alto. Trombonists generally just accept that that’s how their valve is tuned without giving it a second thought. After all, we must have settled on a perfect 4th for a reason, right?

After all, in the early days of brass instrument valves, other tunings were tried. Turn of the century trombones sometimes had their valve tuned to a tritone (E attachment) instead of a perfect 4th (F attachment), for example. And, logically, the F valve on a tenor-bass trombone makes logical sense in theory; you combine the tenor trombone in B-flat and the old bass trombone in F into one instrument. Right???

Well, not entirely. The bass trombone in F has a full length slide that allows you to play low C and B. The F attachment doesn’t really have access to either of those notes. Yes, I know generations of trombonists have accepted the common wisdom that low B is the only note missing on an F attachment, but unless you have an extra-long handslide like on a Conn 70-series bass trombone or some traditional German trombones, that’s not actually true. Modern trombone slides are too short to actually be able to play an in-tune low C at the end of the slide. Of course, players learn to adapt, and many a powerful low C has been played on a modern single-valve trombone. But in these cases, the low C is being lipped down into tune (and sometimes the player doesn’t even realize that they’re doing this, because low C is supposed to be at the end of the slide!) …or it’s just very sharp. In any case, this point is only somewhat important to the real topic at hand, so I digress.

Anyway, the F attachment obviously works well enough that there isn’t a strong reason for most trombonists to consider trying a valve tuned differently. The hardest repertoire ever written for the trombone has been played brilliantly on trombones with F attachments.

However, a perfect 4th valve is far from the only way to get the job done. And, more to the point, there is another way to tune the valve on a single-valve trombone that I would argue is significantly better than the F attachment for the majority of players. Enter the minor-third valve, aka the G valve on a tenor or bass trombone.

The minor-third valve (G attachment) does as you would imagine: rather than lower the pitch of the trombone by a perfect 4th to F, it lowers it a minor 3rd to G. Put another way, you are using a 3rd valve on a typical valved brass instrument instead of a 4th valve. With the G attachment, you have a range down to low D right in 7th position, so you are really only losing one real note (Db) to the F attachment. Below the staff the F attachment is more convenient, but the notes are still perfectly doable on a G valve. However, once you get into the staff, the G valve becomes drastically more useful than the F valve.

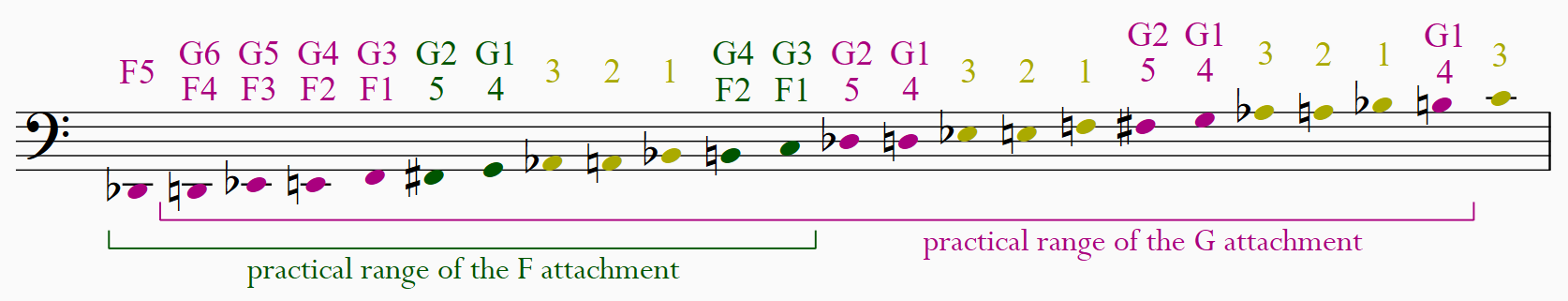

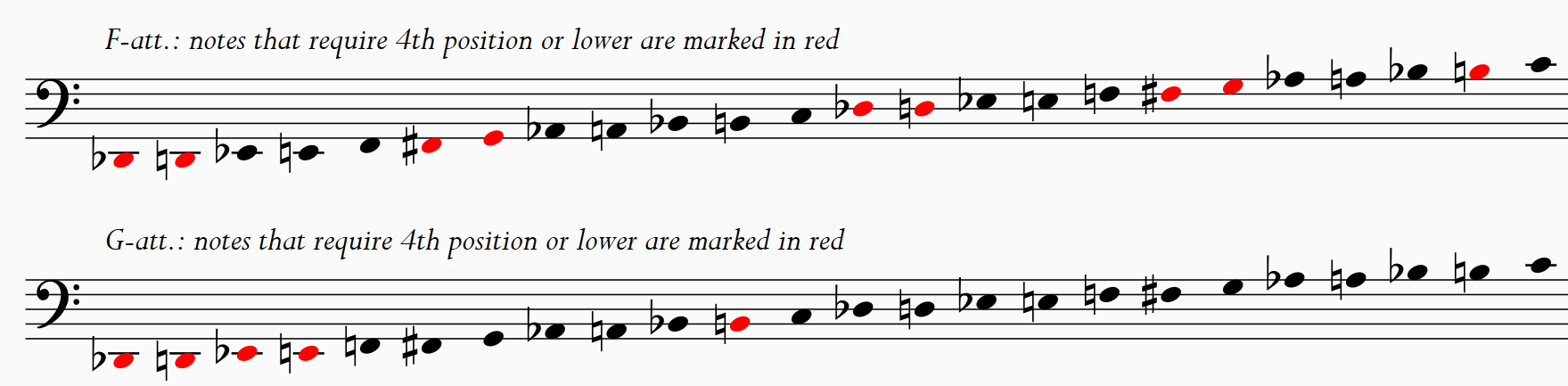

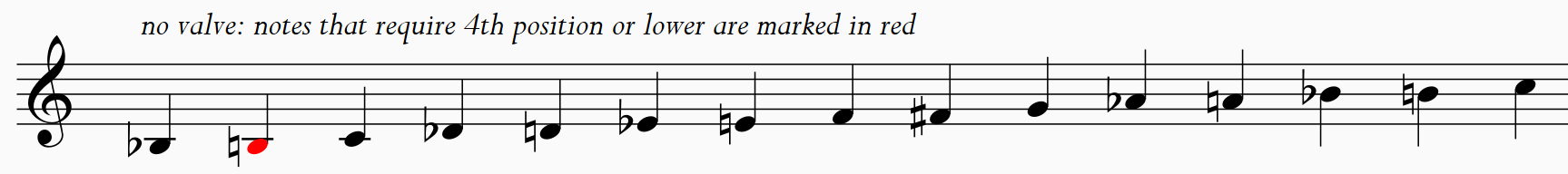

Shown above are the practical positions for the F and G attachments. This is obviously not every possible note the valves can play, but instead the notes that are either not possible without the valve, or they replace the only or most common open slide position. This is an important distinction because, for example, you can play A3 (top of the bass clef staff) in T1 with an F valve, but doing that is the equivalent of playing it in 6th position on the open horn, which is something that is rarely needed when you have a much better option in open 2nd. Contrast that with the B at the top of the staff you have access to in T1 with the G valve. Playing this note in T1 is functionally identical to playing it in 4th position without the valve, which is the standard position for that note. Yes, you can also play it in 7th (which is what playing it in T2 with an F valve is equivalent to), but you would never do that except for specific circumstances like glissandi because 4th is much more secure.

With this criteria in mind, you can immediately see why the G valve is much more useful than the F valve in the staff. The F valve’s highest practical note is C in the staff, while the G valve’s highest practical note is B on top of the staff, nearly an entire octave higher. And on tenor trombone especially, notes in the staff are infinitely more common than those below it, so why would you greatly reduce your valve’s utility in a range you play in constantly to only get a minor improvement in a range you play in occasionally?

With that usefulness in the staff comes the G valve’s greatest strength: with a G valve, the agility you can achieve in the staff is equivalent to that above the staff, an octave higher. There is a reason jazz trombonists often hang above the staff when playing solos at fast tempos; once you get above the staff, you never have to go past 3rd position, so you are far less encumbered by the physical distance you need to move the slide. With a G valve you never need to go past 3rd position all the way down to C in the staff, which is a full octave lower than without a valve and a perfect 5th lower than with an F valve.

I own several trombones with minor third valves: an alto, a small tenor in C, a medium bore tenor, a large bore tenor, and a bass trombone (valves in G and E). They have each proven to me just how useful the minor-third valve is many times over. Of course I own tenors and basses with F attachments as well, and they do the job just fine. But when playing on one of my single F attachment trombones, I often find myself wishing the valve was in G. It is just infinitely more useful for most playing situations.

Of course, there are times when you do need an F attachment. The unison, exposed low D-flat in Mahler 3, for example. But providing an F extension, or even a Gb extension, for a G attachment is perfectly doable and covers these eventualities. When playing a single-valve bass trombone, you deal with a lot more writing below the staff, so in that case the F attachment makes more sense, especially if it has a flat-E pull for a true low B. But for alto trombone, tenor trombone, and even plenty of bass trombone repertoire, the G valve would not only do the job, but do it better than an F valve.

A Shires tenor trombone with a G-flat attachment. The G-flat/major 3rd valve could be a nice compromise for orchestral tenor players who do need the occasional low D-flat, or bass trombonists used to the G-flat valve on an independent bass trombone.

At the end of the day, 99.99% of trombone players will never get a chance to try a G valve for themselves because nobody sells them. Of course custom makers can always do custom orders, but most players would (understandably) want to try a new tuning before committing to an expensive custom order. Not many people will be willing to chop up an F attachment to give the G valve a shot, which is also fair. The only real way for the G valve to gain more widespread appeal is for manufacturers to offer it off the rack, WITH an F extension as standard equipment. Then, just maybe, more people will realize just how great the G valve is, and just how suboptimal the F valve is for a lot of trombone playing.

Thank you for coming to my TED Talk.